My brother spent his last days sleeping outside in Oregon, a couple hundred miles from the small town, Grants Pass, that laid debate about the right to be homeless at the foot of the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court has signaled that they may side with the town, effectively allowing communities to make it illegal for people to be homeless.

This sharp focus on homelessness isn't truly looking at all people who are homeless—but the visible minority of homeless individuals.

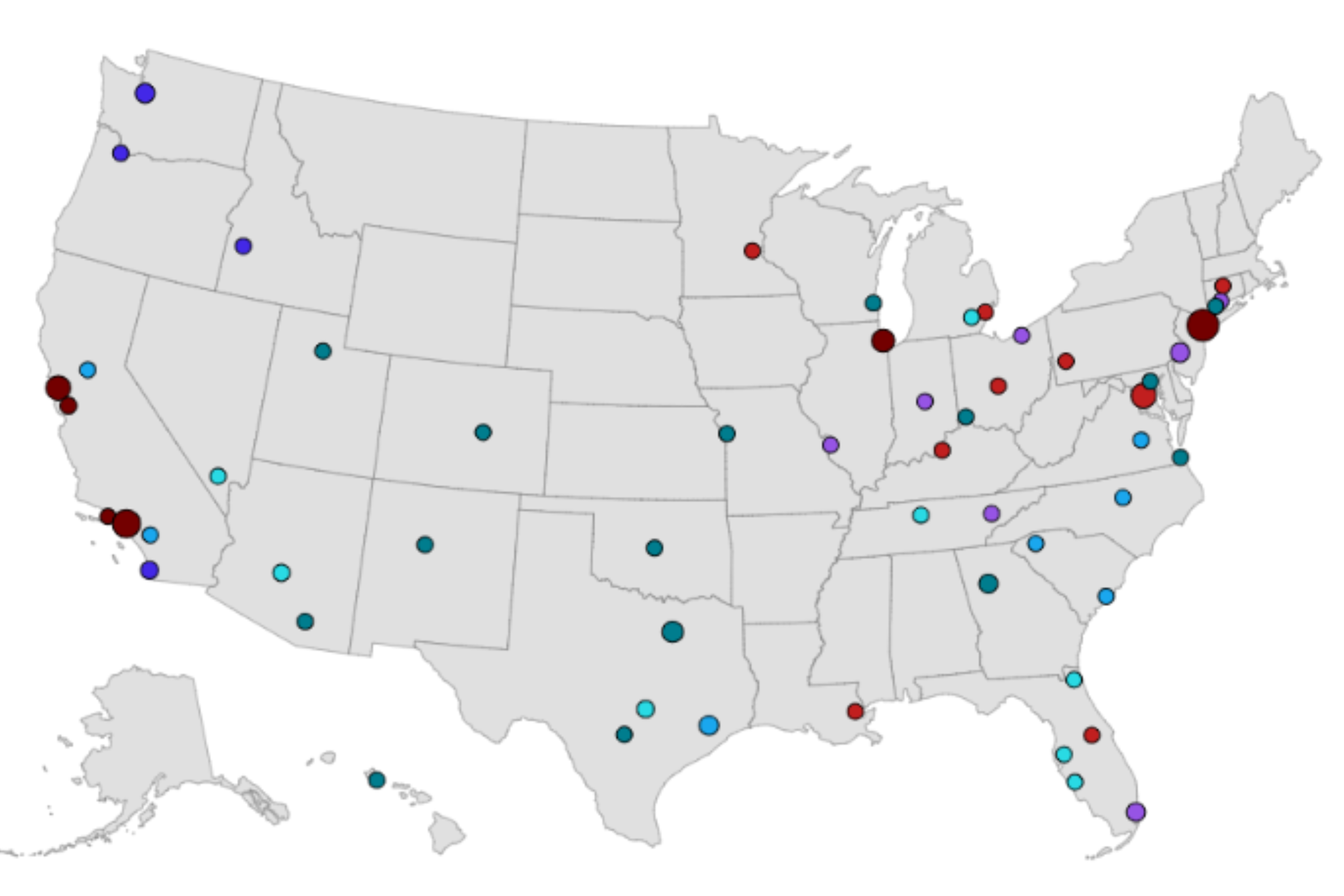

According to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) the number of people living unsheltered, on the streets, in tent cities, or in vehicles has increased by 7 percent since the pandemic, particularly in urban areas.

The unsheltered population's visibility has magnified the issue, especially in California, home to about 50 percent of the nation's homeless unsheltered individuals, most of whom reside in Los Angeles, Oakland, and San Francisco.

The crux of the Grants Pass case is if cities would allow people to camp in "tent cities" when there are shelter beds available.

The problem isn't just the sheer number of shelter beds, it is that our country's $2.8 billion investment to end the homelessness crisis isn't working to help the people who need it most.

Shelters work for people who are willing and able to fit into a system. Chronically homeless people with untreated mental illness are square pegs in a system of round holes.

In the largest study of homelessness in the U.S. since the 1990s, the University of California San Francisco surveyed 3,200 people in an effort to understand the causes and consequences of homelessness in California.

Of those surveyed, 82 percent of homeless people surveyed experienced mental health conditions. And like my brother, 27 percent of these individuals had been hospitalized for a mental health crisis, often before becoming homeless.

Many people with a serious mental illness also lack insight into their illness (meaning they truly cannot process the information that they have a mental illness) which results in mistrust of the health care system, social services, and the government at large.

So how does a person become homeless?

Here's how one story plays out: My brother Jay was living in a not-so-great apartment when he left his key on the coffee table and took a bus to the East Coast with every intention of sleeping on the streets.

He was 20 and had been diagnosed with schizophrenia the previous year. He refused to take medication and experienced auditory hallucinations and visual disturbances that made him believe that he was under heavy surveillance by the government.

With everything going on inside his mind, he did not want to be inside himself. He wanted to be able to move, to walk or hitchhike, and talk to strangers he met along the way.

Our family kept his apartment until the lease expired, when it was clear he had no intention of living inside again.

It's Not About Building More Shelters

In the past few years, there has been a surge in housing, with almost 100,000 extra beds available for homeless people who can utilize shelters, rapid re-housing, and other permanent housing.

Despite the addition of more shelter beds, the number of people utilizing shelters has been declining for years before the pandemic.

I volunteered at the Bowery Residents Committee (BRC) shelter in New York City as a poetry teacher for a few years. In the class, people wrote poems about their stories, often about what had gotten them onto the streets.

While I was volunteering at the shelter, I would encourage people who seemed to be living on the streets and encourage them to the BRC.

From those conversations, I quickly learned about the many barriers that kept unsheltered people out of shelters. Going to a shelter takes vulnerability and trust in a system that may have already let you down.

Despite the best efforts of their staff, shelters are not always safe environments and can be particularly scary for people who have experienced trauma or abuse.

It Is About a Treatment First Policy

Back in the 1990s, the last time homelessness was consistently making headlines, a program and philosophy called Housing First was developed.

Housing First programs work by removing barriers that traditionally kept people out of shelters like treatment or employment. Yet, for so many unsheltered homeless people, treatment for mental health and substance use disorder is a necessary step towards feeling comfortable living in a shelter or in supportive housing.

There's no question that our country has underinvested in mental health. We do not have urgent care walk-in clinics for mental health care. We have the fewest number of in-patient psychiatric hospital beds than any point in history, at 10 beds per 100,000 people, according to the Treatment Advocacy Center.

We need programs that will focus on getting people into Treatment First and coordinate with the shelter system second.

Astonishingly, in HUD's 2022 112-page report to Congress, the issue of mental illness was addressed only three times, and all about Safe Havens, a program that funds small shelters specifically for people with mental illness.

My brother offered another clue as to why some homeless people do not access our existing solutions. When he arrived in San Francisco, he called me with glee: "Ashley, this is a great place to be homeless."

He reported that the weather was great and you could sleep in the parks.

Whether or not you could sleep in the park and if the library was open 24/7 were major amenities to him. He was thrilled that there were so many people that he would listen to him talk about his belief that the world would be ending very soon.

The best explanation I can find for unsheltered homelessness is in the Bright Eyes song Road to Joy: "No one plans to sleep out in the gutter. Sometimes it's just the most comfortable place."

Until we create solutions that address the specific needs of the unsheltered population, there will still be people for whom the most comfortable place is the streets.

Ashley Womble, MPH is a mental health advocate who works to improve the mental health system within the tech and nonprofit sectors. She is the author of Everything is Going to be OK, and has written for Salon, Women's Health, Health, and Cosmopolitan.

All views expressed are the author's own.

Do you have a unique experience or personal story to share? See our Reader Submissions Guide and then email the My Turn team at myturn@newsweek.com.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Ashley Womble, MPH is a mental health advocate who works to improve the mental health system within the tech and ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.