We live in an excellent moment for art. Yes, I'm surprised too. Given the sheer quantity of junk to be seen, such a declaration seems absurdly Pollyannaish. But after a friend asked me to tell him which artists to watch, I was shocked to find my list verging on 50 names. At the top were a solid 10 artists—some already famous, some little known—who seemed not just good, but so good they might enter the history books. (I was counting only artists who belong to our moment. Other living geniuses, like Jasper Johns and Richard Serra, proved themselves in earlier eras.)

Think back to the great years and places in art: 1515 in Rome, or 1912 in Paris. How many of us can cite 50 Renaissance talents, or that many cubists, whose work still shines? Finding so many artists worth getting behind in 2011 must say something about the moment we're in.

Here, then, are the top 10 artists of our time—at least as I judge them. A handful are showing work right now at the Venice Biennale, the world's most important roundup of contemporary art. Many others will have work for sale at Art Basel, the huge commercial fair that opens in Switzerland on June 15. I'm not certain all the artists on my list are flawless, or that I won't change my mind about some of them. But I can say this to anyone who cites today's junk as supposed proof of art's current failure: it's just the dross on which quality work always floats.

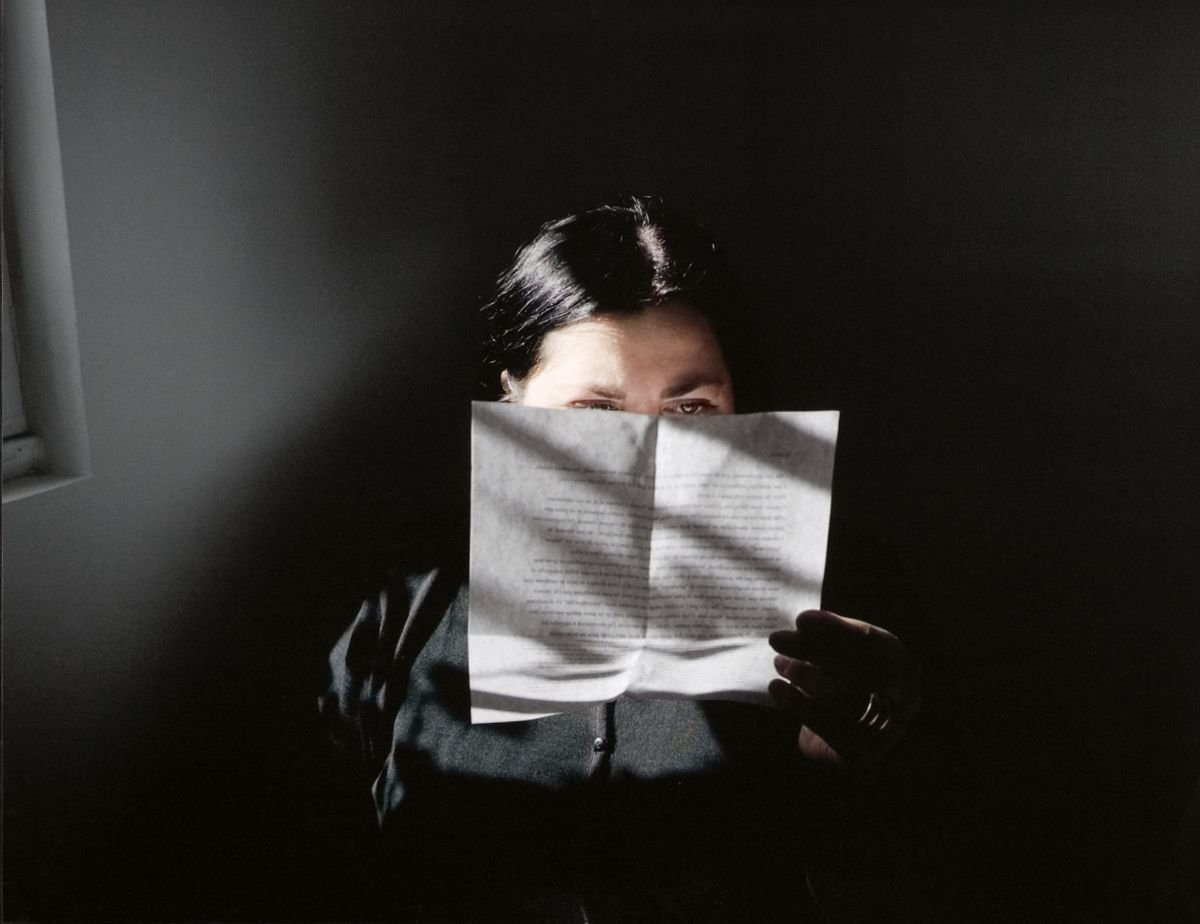

A portrait of the artist, unmasked.

She may be better known than any other artist today. Or rather, the look of Gillian Wearing's art must be known by more people. It's at the root of all those ads in which "average people" are photographed holding hand-scrawled signs revealing what they really want from a bank or a car.

But in Wearing's artworks, which launched her to stardom in 1993, the words have truly been scrawled by the subjects, and are often poignant. A cheery young banker type in suit and tie has made a sign reading "I'm desperate." "In Britain, we're a bit scared of showing our emotions in public," says Wearing, 47, who believes her art is about "people opening up, and saying things they've never said before." Instead of buying the old cliché that portraits peer into souls, Wearing lets her sitters decide what to reveal.

For 2 Into 1, Wearing asked a middle-class mother to talk about the virtues and vices of her two 10-year-old sons and also got the boys to dish about Mum. Then she videotaped the boys lip-syncing to their mother's taped words, and the mother doing the same to her sons'. All three protagonists are thus conveying someone else's opinions of them—often cruel ones.

One of her most striking, most disturbing projects is a series of photos in which she has cast masks of other people's faces, then photographed herself wearing them, leaving a seam where her eyes peer through the rubber. She's donned the face of her adult brother, and of herself at 17. And, in a new image made specially for NEWSWEEK, she's created a mask of what she looks like today, then put that on as an assumed persona. "At the heart of my work is portraiture," Wearing says. But her art is as much about resisting that genre as embracing it.

The Picasso of the moving image, the Leonardo of sound.

In January, something unheard of happened in New York. A show of substantial contemporary art—of video art, no less—became a popular sensation. People lined up for hours in the bitter cold to take in a new work called The Clock, by the Swiss-American artist Christian Marclay.

The piece was nothing more than a 24-hour montage of film clips about time and its keeping, but it delved deep into how culture—the culture of movies, in this case—helps track the unfolding of things. "You always think that artists are above pop culture, but no, that's where we live," says Marclay, 56, who moved from New York to London a few years back. "Entertainment is a dirty word in the art world." But by pulling Hollywood apart at the seams—he was one of the first artists to make work by sampling old movies—Marclay is revealing the artful way it has always been knit together.

I balked at first at how The Clock had such immediate appeal, because what's instant sometimes lacks depth. But Marclay's likable piece seems profound, thanks to its fiendish complexity. After years of work, Marclay got his thousands of clock shots to synchronize with the actual time in the place where they're being seen. The work's soundtrack is in such contrapuntal play with its visuals that Bach would have been proud.

Yet there are also Marclays that are absolutely simple. For a video called Guitar Drag, he mounted amplifiers and speakers in the back of a pickup, plugged in a Fender Stratocaster, then dragged the poor instrument along country roads. As the video progresses, what begin as power chords become a barely audible rumble, released by a guitar that's now kindling. The piece was taped in Texas, where two years earlier three white men had similarly dragged a black man, James Byrd Jr., to his death.

Marclay, who is tall and thin with close-cropped hair that's beginning to gray, is a legend in the DJ world. He's credited as one of the inventors of "turntablism," the art of using spinning records as noise—and rhythm machines. And he is the artist who, more than anyone, brought sound into the hallowed halls of fine art. Last summer, when the Whitney Museum hosted a Marclay retrospective, you never knew whether you'd encounter a singer improvising from a Marclay "score" (nothing more than a compendium of sound effects transcribed from comic books) or a musician playing Marclay's Wind Up Guitar, a hybrid of plucked strings and music boxes.

Marclay's career began in the late 1970s when, as an art student newly arrived from Switzerland, he hung around New York's alternative scene. He says the groundbreaking bands he saw prompted a question: "Why wasn't music considered art?" Marclay, a visual artist who can't read or play a note, set about making sure it would be.

She builds better worlds.

Marjetica Potrc has made some important art: she's built dry toilets for Latin American slums and promoted a water jug for Africa that can also absorb the force of land mines. She's taken the idea that art can change the world and made it come true. Sure, her art-world actions don't do that much actual good. Instead, they do what art does best: they talk about how the world might be better.

"I believe in art. People need art to negotiate their world," Potrc says. And the depth of that belief may be this artist's true contribution.

Potrc (pronounced "PO-turtch," with Marjetica sounding close to "Mari-EH-tee-tza") was born in 1953 in Ljubljana, Slovenia, where she still lives. She got her start in architecture, but began making building-themed art about 15 years ago.

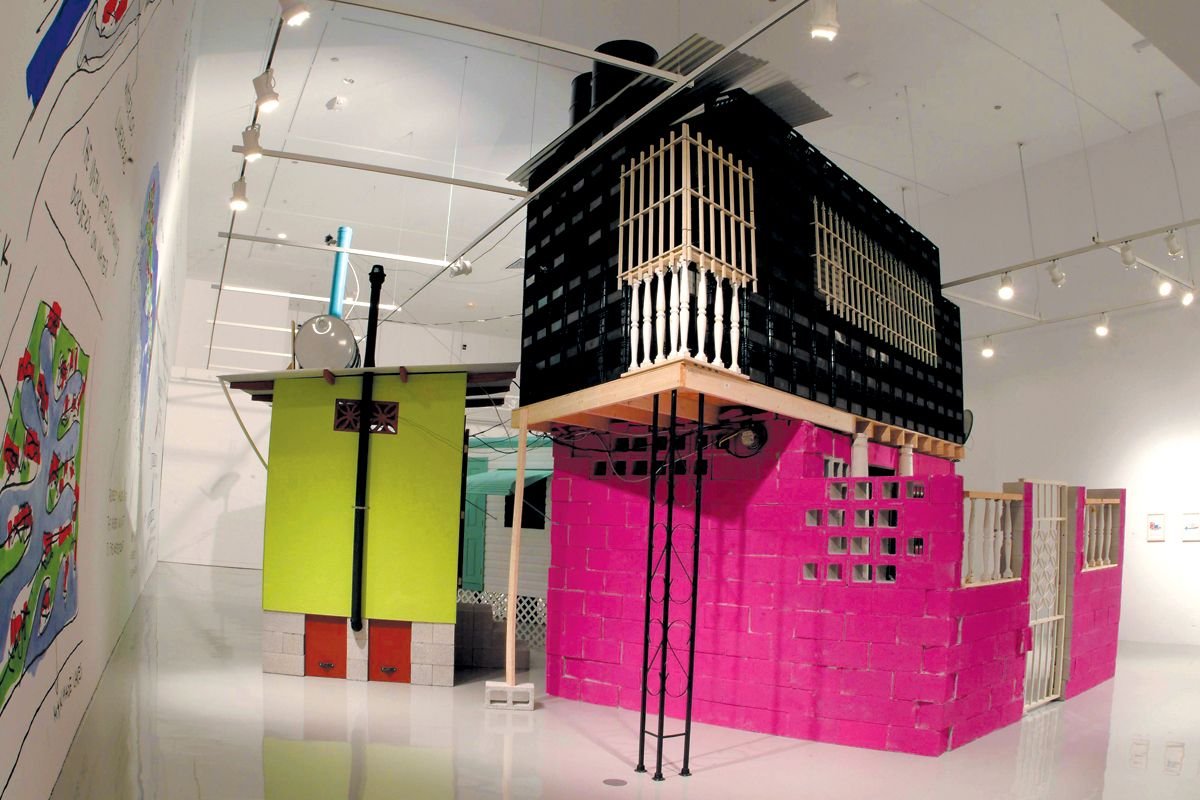

A typical Potrc begins with a structure or situation she finds in a distant place—say, Venezuela or Rajasthan, India—then tweaks to make more livable. "We should respect people in favelas, and learn from them, and their living conditions." Other work comes closer to sculpture, as she mashes up constructions: in a big installation at MIT called Hybrid House, Potrc set down a wild building that hybridized features of buildings from Caracas, the West Bank, and West Palm Beach. By colliding three such different visions, Potrc achieves a surrealist edge that also embraces the real.

Painful videos reveal life's brutal truths.

A deaf choir grunting out a Bach cantata.

A naked amputee clutching a nude person with limbs, so that together the pair looks like one complete body.

A young woman dying from decaying bones, interviewed in bed about the pain she is in.

Artur Żmijewski himself uses the word "brutal" to describe his work, and his videos are indeed as hard to watch as any art I've seen. They are also profound and important and even humane, in the same way Goya's brutalities are. Why not help deaf people sing Bach, regardless of the ugly results? Why flinch at pain seen up close?

"I'm not a good guy who wants to change the world for the better," says Żmijewski (pronounced "Jmi-YEV-skee"). But he's happy to reveal that it might need some changing.

The 45-year-old Polish artist describes living through the fall of the Soviets and then the advent of a rapacious capitalism he saw as "a kind of virus that infects each mind—people didn't expect the dark side to this freedom." He headed to art school on a quest for a way out of the morass: "I was looking for a kind of language, and I realized that art could be that language—that art could help me understand the world." He discovered that video was his best bet for simply getting at that world and explaining it.

A piece recently screened at the Museum of Modern Art in New York presents footage of a group of Polish sculptors, of no particular note, whom Żmijewski paired with factory workers to make public art about the virtues of labor. The sculptures that get made are as lame as you'd expect, but there's something poignant about the sincerity that went into their making, showing lefty ideals still at work. The piece is almost sweet. "Maybe I was tired, a little bit, with the brutality," Żmijewski says.

An antidote to the pictures Hollywood is making.

Tacita Dean doesn't go much to movies. "Hollywood bores me," she says. That comes as a surprise, since Dean has used old-fashioned film stock and projectors to make some of our era's best art. (Her first American retrospective is currently in planning at the Smithsonian's Hirshhorn Museum.)

Film may be Dean's medium, but she uses it more to paint pictures than to tell stories. She makes landscapes with it. Banewl, from 1999, is an amazing 63-minute contemplation of a solar eclipse, as watched among cows in Cornwall, England. Fernsehturm (German for "TV Tower") reveals the passing scene at a revolving restaurant above Berlin, where Dean lives, and yields insights into the fall of the wall and the urban sublime.

Dean has also done interiors. A recent piece surveys a gallery of sculptures by Joseph Beuys by showing only the empty walls of the rooms they're displayed in. That's typical of Dean's crabwise approach—her films examine a subject without simply revealing it. "They're not that informative; they're more observational, about depiction," she says. Dean achieves what I call the Cézanne Effect: the ability to take a seemingly straightforward look at the world and make it have unending depth.

Dean was born in 1965, into the middle class in the tidy British county of Kent. "Art was an escape from how I was raised," she says, explaining how she fled to art school in Cornwall "to be very far away from Kent."

One fact of Dean's biography may be a red herring in explaining her art: her grandfather was one of the founders of Ealing film studios, though Dean says that was barely relevant to her upbringing.

Another detail may be significant, but more delicate—Dean has long suffered from almost disabling arthritis. She doesn't want to be known as an artist of illness ("It's like Roosevelt and his wheelchair"), but acknowledges that the stately tone of her work could be linked to her health. "I plod through the world slightly slower than everyone else."

See her artistic response to a 'Dear Jane' letter …

A male art critic can be forgiven some nerves before an interview with the Parisian artist Sophie Calle. Calle isn't always kind to our sex. An ex of hers who dumped her by email got his comeuppance in Calle's exhibition at the last Venice Biennale: she documented 107 women "responding" to his letter, including a sharpshooter blowing holes through it and a female parrot tearing it to shreds. In an earlier piece, Calle came across a stranger's address book, interviewed his contacts about him, then published the resulting "profile" in a series of newspaper pieces.

With all this in mind, I was caught off-guard when I met the surprisingly pleasant 57-year-old at a Tribeca café one morning. There was not a shred of art-star glower.

Maybe that's because she came to her artistic vocation by accident.

Calle explains that she began by just doing peculiar things, such as photo-graphing strangers she followed, or documenting 23 people she'd invited to sleep in her bed. It was others, she says, who first described those actions as art and her as an artist.

It is the unartiness of Calle's work—its refusal to fit any of the standard pigeonholes, or over anyone's sofa—that makes it deserve space in museums.

A common misperception is that Calle's art is all about her. "My work isn't a diary. If it was only therapeutic, i'd rather buy myself a dress."

His interactive works are a commentary on existence.

He's one of our best artists, but luckily Francis Alÿs came late to his calling. When he first labored to make art, with scant background in the field, he made art that was all about labor. For all the years since, his art has talked about the exertions we all make to survive.

In one video we see the artist pushing a huge block of ice through the streets of Mexico City, where he lives, until his giant load is no more than an ice cube to be kicked. Watching him complete an absurd, self-imposed task reminds us of ourselves most of the time.

For his piece When Faith Moves Mountains, Alÿs got 500 shovel-wielding volunteers to line up at the edge of a huge dune and, as per the work's title, push the first few inches of sand up over the top and down to the bottom of the other side. Had they continued for years, their "mountain" might have moved to Brazil.

And then there's Tornado, a wild new video in which Alÿs hand-carries his camera into the raging center of oak-sized Mexican dust devils. He's yet another artist "at the eye of the storm," but this time not metaphorically.

Alÿs, now 51, was a Belgian architect working in Mexico City when visa problems stranded him there in 1989. He took advantage of the break to try making art. As a latecomer to the business, it seems as though he could only distill it to its strange essentials, as a pointless effort to reach vague goals that aren't clearly worth reaching even once you're there.

In another video, called Rehearsal I, Alÿs himself attempts to surmount a steep hill in a crummy Volkswagen Bug. An Alÿsian catch makes the task more complex: he syncs his driving with a recording of a Mexican brass band rehearsing a tune. As long as the band plays correctly, he steps on the gas; when it stops for a flubbed note, he lets his car roll back. The musicians need more rehearsal; Alÿs never reaches the top.

This may seem to be art about how strange and hard it is to make art. But it also comes to standas all art does, deep down—for being alive and striving to do anything in a universe that grinds all efforts to dust.

Photographic compositions like old-master tableaux.

He made his first important works while today's other leading artists were still in art school—or grade school. That makes it all the more impressive that Jeff Wall's art feels so current.

If I came cold to Destroyed Room, the huge, lightbox-mounted color photo that launched Wall's career in 1979, I would hardly know it was three decades old. Its vision of a domestic interior torn apart by unseen forces achieves a perfectly contemporary blend of pure documentation, Hollywood staginess, and the impact of old-master tableaux. More than anyone, Wall took the traditional art of still photography and used it to launch a new genre called "photo-based art." His pictures have stronger links to classic paintings, and to the 1960s avant-garde, than to Alfred Stieglitz and Ansel Adams.

Speaking from Vancouver (despite worldwide acclaim, the 64-year-old has never abandoned his native city), Wall recalls a moment in the 1970s when the most advanced artists, inspired by Marcel Duchamp's "anti-art" stance, had become "iconophobes," giving up on making pictures altogether. That, he says, made him extra keen to "recover the sense of being a picture-making artist … to move forward in time with the old pictorial art, that never gets old."

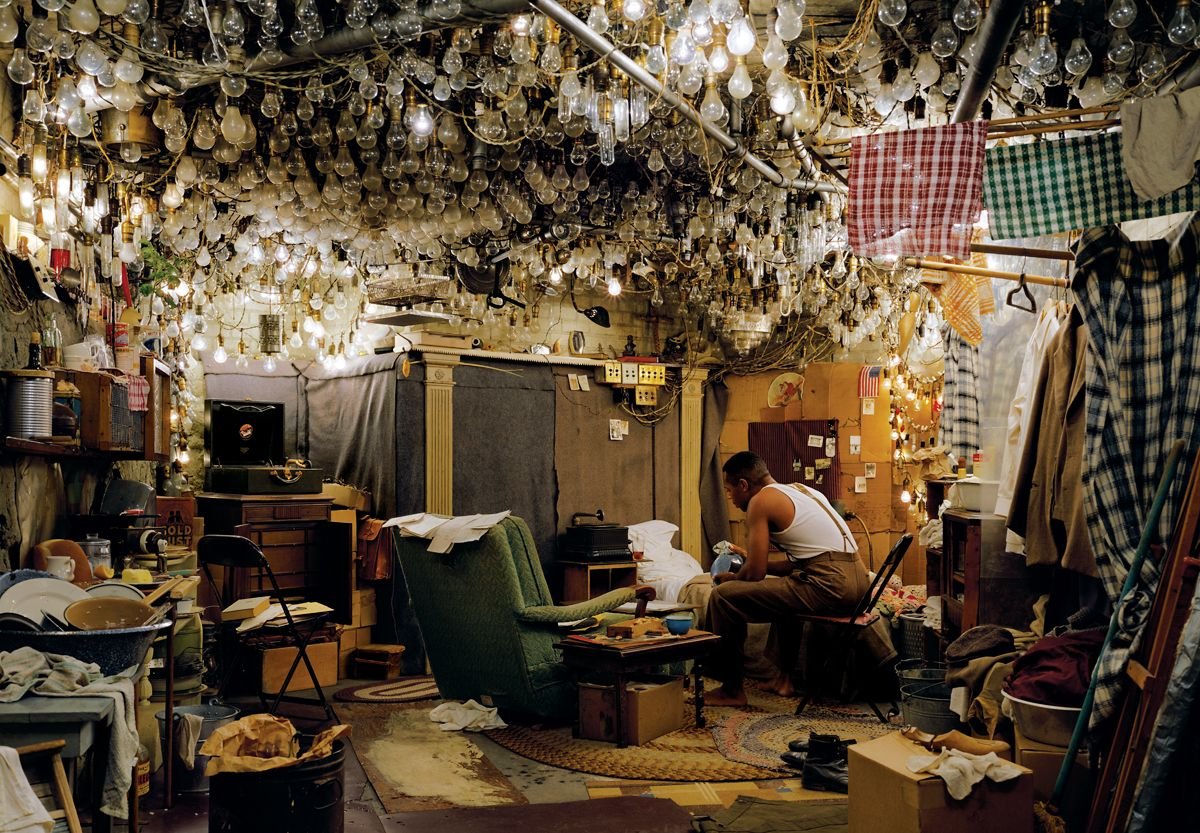

Wall has made photographs that seem explicitly political: a pseudo-documentary street scene that depicts a racist encounter, or a surreal ghost scene set in Soviet Afghanistan, where dead Russian troops resurrect. He's also made the straightest of documents, showing street corners in Vancouver and basement still lifes. And he's made pictures that are simply strange: a naked giantess, maybe 70 years old and two stories tall, visiting a library; a lone black man in a basement lit with 1,369 bulbs, just as described in Invisible Man, Ralph Ellison's novel about race.

For a long time, Wall's photos were read almost as stand-ins for theoretical texts about the nature of society and the meaning of images. But recently he's been allowing his art to float free. "If [viewers] just saw what I said I did, it would be lifeless," he says. "The more people see it differently from me, the happier I am."

For three decades, Wall has been testing the full range of what pictures can still do and mean, after anti-art had "proved" them dead.

He collapses the high and the low.

We've heard of the man who mistook his wife for a hat, who could describe different objects but couldn't recognize what they were. He had a neurological condition called associative agnosia. I believe that Jeff Koons, perhaps today's most famous artist, has an artistic condition you might call aesthetic agnosia. Koons can see the difference between classic paintings and pornographic photos—he collects the paintings and has riffed on the porn—but refuses to admit they mean different things.

Even after 30 years, Koons's mashups of high and low—a dog knotted from balloons, then enlarged into a public monument; a life-size bust of Michael Jackson and his chimp in gold-and-white porcelain—still feel significant. "The hierarchy of things is a kind of defense mechanism that just alienates," says Koons, 56. "Whatever you respond to is absolutely fine."

Sitting in his lab-clean studio in Manhattan, he expounds on the full meaning of a new piece: a facsimile of the Venus of Willendorf, one of humanity's first sculptures, that he's twisted from balloons and is enlarging as a towering marble. For Koons, the aesthetic agnosiac, the piece isn't a wacky sendup or a dada collision of opposites. It's a real inquiry into the sexual content of our earliest art. "It's really about expansion, trying to create a vaster world, a more interesting world," he says. That, for sure, he's achieved.

Selling diamond-studded skulls and unicorns in formaldehyde.

Damien Hirst was the only artist who wouldn't be interviewed for this project. That's just as well. I couldn't imagine asking the necessary questions: "How is it that your work has managed to encapsulate the essence of what it is for art to sell out? How did your whole career become a metaphor for how consumption has become our guiding force?" That is precisely what Hirst has achieved. Achieving it has made him a great artist.

Warhol once said, "Good business is the best art." His studio was called the Factory, and it turned out art the way you'd make widgets. Hirst has surpassed him: he's shown how the business of art, with its bubbles, may be the best business for today's artists to explore.

Take Hirst's diamond-studded platinum skull. Its bling matters less than the $100 million tag the artist decided to attach to it, more a symbol than a statement of price. When the skull did sell, it became clear that Hirst was part of the consortium that bought it, giving the piece a performance-art angle.

Yet the work doesn't celebrate selling out. It's a skull, and has the same grim edge as Hirst's other art supplies: cut-up animals, dead flies, and drugs. Hirst may be laughing all the way to the bank, but his art leaves the rest of us sobered.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.