"When someone in your band is smoking speed out of a lightbulb in Finland, you know you've got problems," Brody Dalle, former frontwoman of L.A. punk outfit the Distillers, says of the band's 2006 breakup between sips of a European vitamin drink.

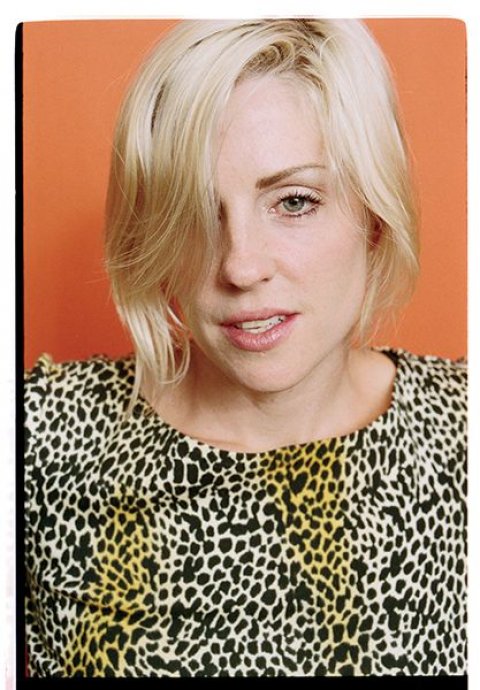

A little after 11:30 a.m. on a recent Monday, the 35-year-old Australian-born musician met with Newsweek in Manhattan's over-chic NoMad Hotel—the decor includes hexagonal toilet seats in the bathroom and vaguely phallic bird art—to discuss her first solo project, Diploid Love (available for download, and on vinyl and CD), as well as her path from the Distillers days to the NoMad.

Dalle's health consciousness combined with the hotel's bourgeois ambience would not have fit with her early career, during which she had a "F**K OFF" tattoo (with bat wings and a red bow) inked on her shoulder, an amphetamine-fueled band disbandment and a constant struggle to cope with childhood trauma.

It would be wrong, however, to say that Dalle has lost her edge by eschewing self-destruction. She says she was able to finish her first solo project largely because she has started taking care of herself. "I am actually happy for the first time in my life. I feel complete," Dalle says. "I had spent a lot of my life floundering and feeling lost." Her solid home life—she has an 8-year-old daughter, Camille, and a 2-and-a-half-year-old son, Ryder, with husband (and Queens of the Stone Age frontman) Josh Homme—belies her traumatic past.

"I grew up with a single mom, and my dad was pretty much absent," says Dalle, who was raised in Melbourne, Australia. "I was sexually abused when I was little. I wound up going through court cases and therapy and all this kind of stuff. I felt mistreated by men, and used and abused. I think that's probably why I felt like I was floundering."

She began exploring music around age 7, starting with a borrowed guitar until at 12 she was given her own instrument, a "piece of shit, an acoustic with a really wide neck."

A few years later, she started taking classes at Rock 'n' Roll High School, a feminist educational organization in Melbourne that trained women musicians. At 16 she started her first band, Sourpuss. The group landed a set at Australia's Summersault Festival, where she met her first husband, Tim Armstrong, lead singer of the Bay Area punk group Rancid.

Sourpuss didn't last long: The band broke up after one member was raped and murdered while hitchhiking. "They found her body on the road," Dalle says. "It was really f***ed up."

While still in Australia, Dalle started the Distillers, but after she received compensation from the Australian government for her childhood abuse, she moved to L.A., seemingly bringing the Distillers to an end. "I used that money to get the f**k out of Australia," she says. In L.A., at the age of 18, she married Armstrong and wound up relaunching the band with L.A. musicians.

The band rose to prominence largely because of the track "Seneca Falls," but the U.S. wasn't good for Dalle's personal life. She and Armstrong had an unhappy marriage and divorced in 2003. The turmoil propelled Dalle deeper into her music, solidifying her reputation as a talented vocalist—her voice ranges from hoarse screaming to a sultry contralto—and an innovative hook writer. Despite a huge following, the Distillers disbanded in 2006.

"I think we were overwhelmed as people in a band on tour for two years," she says. "We'd come off touring and had some nasty habits, and we weren't talking."

Six months after the band broke up, she got pregnant with Homme (their daughter, Camille). While she says this began "a new chapter" in her life, her identity crisis worsened. She felt "weird" during her pregnancy and put on 55 pounds. Then came "really bad postpartum" depression. When she finally had the time and mental energy to return to music, she launched an alt-rock supergroup, Spinnerette, in 2007, but the project was skewered on Pitchfork as out-of-date "genre Dumpster-diving." Dalle effectively went on a music hiatus for four years.

Dalle realized she had to make more time for songwriting and performing, and to find the balance between being a rocker and a mom. Since she started pursuing her solo project, this savvy scheduling has come to include sometimes taking her kids on tour, during which she gets up at 6 a.m. and does "mom stuff" until sound check, plays a show at night, goes out after the show and repeats the process again the next day.

"I have to admit, I cried quite a few times," she says of a recent tour. "It was gnarly, but it was awesome. My kids always take priority over everything, [but] if the balance gets too heavy on the one side, I have to make sure to take out the scale" and redistribute the weights.

Diploid Love is proof that Dalle is balancing things masterfully. The album is heavily influenced by Nirvana and Hole—bands she grew up listening to—but moves far beyond the predominantly guitar- and drum-heavy conventions of grunge and punk.

The vocals, which range from husky to high and soft, include the rough, riot grrrl-inspired energetic guitars characteristic of Dalle's earlier projects, but with sounds that didn't appear frequently in that style, such as violins, tambourines and even a giggling toddler. "We'd be listening back to something, and she would suddenly go, 'Quick, give me a microphone,' and she would sing a brand-new melody that would take it to another level—same with guitar parts and synth lines," says Diploid Love co-producer Alain Johannes, who calls Dalle a "supreme badass" for her mostly self-taught musical skills. "She just starts singing an amazing countermelody, [something] super hooky and cool, then grabs the guitar or goes to the synth and finds it immediately."

The deeper question about Dalle's new project maybe isn't so much why—she is a lifelong musician and at a point in her life where she's ready to pursue her own projects—but why now?

There aren't a lot of aggressive female rockers these days. Some have suggested that the recent rise of the Russian artistic collective Pussy Riot has enabled Dalle's return to a music world that has been missing strong women since the riot grrrl movement's decline in the mid-1990s.

The rekindling of a cultural appetite for rebellious female vocalists might also be cyclical, Dalle suggests. While the riot grrrl years constituted "a golden era" of women playing aggressively, the late 1990s and early 2000s saw a "backlash" against socially subversive rock, especially that of women artists. The music genres that rose in its stead were quite traditional in terms of gender. There were the super-macho rap-metal acts like Limp Bizkit, while the most famous female singers, such as Britney Spears, were "all about sex and the way you looked and your body," Dalle says. She hopes these preferences will wane, predicting that music fans are "going to get sick of it."

In the meantime, Dalle tries to protect her kids from the hyper-sexuality of pop culture by exposing them to as little of it as possible. It seems to be working. Dalle's daughter is into animals and "could tell you every breed of dog that's on the planet." She has already started writing songs and now listens to the defunct female-fronted British rock band Siouxsie and the Banshees.

Dalle is a bit more worried about her son's trajectory. "I'm like, 'What do you want to do?' He's like, 'I want to be a fire truck,'" she says with a laugh. "I don't know how that is going to happen."