On a Saturday afternoon in October, Luton Town are playing away against local rivals Stevenage. To those weaned on the 40,000 seat behemoths of the English premiership, Stevenage's Lamex Stadium, which today holds 5,236 but has a capacity of around 7,000, seems almost a parody of a football ground. The stands are low. One in particular, behind a goal, is only a few rows of spectators deep and peters out entirely two-thirds of the way across the pitch. The corners are open. Hoardings advertise Stevenage van hire and Mather Marshall estate agents.

Luton's travelling support are vocal; they shout their team's name with a glottal stop rather than a hard consonant: "Come on Lu'on!" 22-year-old Luke Wilkinson puts Luton ahead in the ninth minute with a headed strike. Stevenage equalise in the 33rd. Then, in the 69th minute, Luton's manager John Still brings on another striker – Charlie Walker. At the back post, Walker heads through the legs of Stevenage goalkeeper Chris Day. The goal is disallowed, but the day is still a significant one for Walker, marking his first ever appearance in fully professional football. Last season, Walker was playing for a part-time club in East Sussex and had a day job as a builder. This season, he is living the dubious dream of the lower leagues.

In the 83rd minute Alex Wall scores for Luton and the match is won. After a shaky start to the season, in which Luton won a mere four out of 10 league games, the club's luck appears to be changing. But most of its players are yet to get a taste of what top-level sporting success would really mean. Later, on the 15-mile journey back to Luton in the players' coach, I ask Jonathan Smith, a 27-year-old midfielder known as "Smudge", originally from Preston, what he plans to do when his sporting career comes to an end. Smith has some qualifications, at one stage there was even a place at Liverpool John Moores University on the table. Now, though, he looks out of the coach window, towards the One Stop Cash and Carry, on a drab Luton street.

"Work in that joint," he says ruefully.

Between the Gutter and the Stars

I came to Luton after meeting a former schoolboy footballer. He had won a scholarship to an American university, based partly on his sporting achievements. Later, he said, he wanted to come back and play football at the bottom of the English game. He knew already he was not good enough to play in the top flight, but he thought that somewhere much further down might be an achievable goal.

Money was his reason. It was now possible, he suggested, to make good pay down there. Not the massive lucre of the top of football, the tens of thousands of pounds per week earned by Wayne Rooney or Gareth Bale. But in the fourth tier, he suggested, £50,000 per year was possible – £75,000 perhaps. Maybe even £100,000. A hundred thousand pounds for playing in the sporting netherworld? I wanted to see if he was right.

I approached clubs in League Two, the lowest fully professional rung of English football. The nomenclature is complicated. The top flight has, since 1992, called itself the Premiership, turning the old first division into the second tier. In 2004, the first division rechristened itself the 'Championship'; the third tier became 'League One'. League Two, the next one down, is the fourth rung, where Luton sits: the bottom of this particular world.

In the past 20 years, broadcast money poured into the top of English football. In 1992, when the top 22 English clubs broke away to form the premiership, the move allowed them to capitalise on the new technology of pay-per-view television. British Sky Broadcasting bought the initial rights to 60 live premiership games a year (the BBC got highlights) in a five-year deal worth £191.5m. While that figure seemed staggering at the time, it would massively increase in due course: come 2012, a new three-year premiership deal, split between Sky and BT, was worth over £3bn. And the clubs at the top of the ladder began to rake in profits of their own. In the 1991/92 season, the combined revenue of top-flight English football clubs was £170m, of which only 9% came from broadcasting; by 2012/13 that figure had reached £2.5bn, and 47% came from TV.

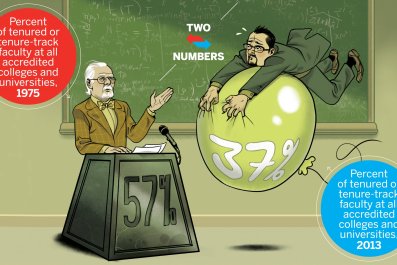

As this new money saturated the premiership, the wages of the best players shot up. In 1991/92 the entire top-flight wage bill was £75m; by 2012/13 it was £1.8bn. A November 2014 survey put the average premier league player's salary at around £2.3m per year, or £43,717 per week. But the gap between the wealthy clubs at the top and the struggling ones at the bottom widened too. In 2012/13, premier league clubs received an average of £60 million each in broadcast revenue. Clubs in the fourth tier, at Luton's level, receive a 100th of that amount. It seemed that the pursuit of a leather ball, the beautiful game that the English invented, had become a mirror for a wider English phenomenon: deepening economic and social inequality.

Mark Cullen is not tall; his hair is straw-coloured. Born in 1992, he grew up in Ashington, a town outside Newcastle. Cullen once scored in the premiership. The goal came for Hull City in May 2010. Just turned 18, he nodded in a cross from George Boateng against Wigan in a 2-2 draw. It was a very bright start, yet the teenager could not keep a place in the team. Loan spells elsewhere did not work out. After a stint at Stockport County, Cullen signed for Luton in May 2013. "Obviously I did some things that a lot of players will never maybe get the chance to do, like play in the premiership and score, especially at a very young age, like," he told me. "So to be able to have that on a CV is really good. But I have got some regrets in the way some things worked out, but that's football, innit, in a way like. It doesn't always go the way you plan."

Many of his fellow players were formerly on the books of bigger teams, if only as teenage trainees, and Walker isn't the only one to have played part-time at some point. Lower league football is a mixing vessel, a place of oil and water. The ascendant meets the descendant but which direction you are moving is not always clear, and can change rapidly when Saturday comes.

Down in the fourth tier of the English game they are – in parallel – both in the gutter and among the stars. Given that the aspiration of so many young boys is to play professional football, even these men at the bottom of the professional game are highly selected.

Between the gutter and stars then, but always in Luton.

Making it Big

I spent an afternoon in the company of Jonathan "Smudge" Smith and Danny "Fitz" Fitzsimmons. Both had experienced major injuries. Fitz had the scar from an anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction operation down his knee. "My mate did his ACL when he's 18 and I never thought that's going to happen to me," he explained.

Smith's wound was distinct; just below his right knee a metal pin pushed up hard against the skin. That is the legacy of Boxing Day 2013, when a bad tackle from Barnet's Jon Nurse broke his leg in two places. The midfielder was back in a Luton shirt four months later, brought on for a few seconds in the last game of the season by Still, largely for the benefit of the fans. He was fully fit by the start of 2013/14.

Such a rapid recovery was permitted by an intramedullary nail. The nail holds the sections of the broken bone together and allows much more rapid healing than with the use of a traditional cast. "A few years ago, like, that would have probably ended a career or at least been a year out, two years out," Smudge explained to me later. "But you put the nail in, you can pretty much put weight on it straightaway, because it's supporting it. You're on the bike, all of a sudden, within the week you're putting weight through it."

What he would he have done had the injury ended his career? "It's hard to say really," he said. "I've got a few options that I might have been able to look into. But football's obviously my life, like, so it would have been a big disappointment for me, like. But you have to get on with it, don't you?"

We drove from the training ground in Smudge's car to the flat Fitz shares with the team captain, Stephen McNulty, when McNulty is not with his family in Liverpool. The place had the unmistakable feeling of male digs – sparsely furnished beyond a large television, copies of Mirror Sport and the Daily Star, and an ironing board. We walked into town. "Kill the day, know what I mean?" Fitz said. "We're not from round here, so there's not a lot for us to do. Get a bit bored, know what I mean."

Beyond the training ground, would they be recognised? Fitz was a junior in the club hierarchy; he had never played in the first team. Smudge, though, was central to the line-up, he had made some 50 appearances. If there were well known faces in the Luton Town team, he would be one of them. The three of us walked through the shopping centre. We sat in Costa Coffee. Only one set of heads turned and it was unclear if the two women clocked Smudge and Fitz as players, though Smudge told me later he was sometimes recognised when he went swimming.

Smudge wanted to buy skinny jeans. He looked in H&M. Eventually we wound up in River Island. I waited with Fitz in the basement by the shoes looking at brogue boots for £60 and other high-street versions of recent couture. I realised that was exactly what these players were, mass-market copies of famous footballers. Mr Porter sells Givenchy brogue boots for £820; more than 13 times the River Island price. Luton bought Smith for £50,000 in January 2013. This year Manchester United bought Angel Di Maria for £59.7m from Real Madrid.

The great discrepancies extend to player remuneration too. Luton Town's entire pre-bonus wage bill, around £1.25 million, would sustain Manchester United's Rooney for just over four weeks. Gary Sweet, Luton's chief executive, said salaries for his senior players run from less than £25,000 to more than £75,000 per annum. Youth trainees are on much less, but even in the senior squad, some players earn "eight or nine times more" than others. At the top end, these wages are several times the English national average. But they have to be seen in the context of the average length of players' careers – a mere eight years according to the Professional Footballers' Association, the players' union.

Wastage

At the training ground close to the M1 motorway I watched Luton's academy players, the 16-18-year-olds, do their training. The relationship between the youth team and the senior squad seemed a simulacra of that between the fans and the team itself. The fans had a highly personalised conception of the Luton Town players, often expressed using nicknames. Likewise the 16- and 17-year-olds in the academy knew the stats of the senior men. They knew their names, their records. They had favourites. The senior players generally did not deign to know them back.

I watched a training exercise. My real interest, though, was the wastage. According to the PFA, a mere 15% of those given an academy contract at 16 are still involved in the game at 21. The PFA's deputy chief executive, Bobby Barnes, would later tell me frankly that no other industry would tolerate a situation where 85% of entrants are cast out five years later.

That is perhaps an overstatement; entertainment and the arts have similar rates of attrition. Still, the wastage in football is severe, and the kids who don't make the cut have given up the chance to stay in full-time education, further limiting their horizons.

At Luton, there is a tremendous variation in the academic credentials of those entering the academy, from boys with A*s at GCSE to those with few qualifications at all. The BTEC they study for sits low in the spread of British educational qualifications – it is not a path to a good university. These slim educational pickings are one reason why middle-class parents are often reluctant to allow their children to take up academy places. The British football system is also a profound contrast to the American set-up, where university athletics is an accepted path to the professional game in many sports.

Christian Burgess of Peterborough United, one of the few university-educated players in the English game, is critical of the current system, in particular of the inroads football takes on school time even before academy selection at 16. "The youngsters are coming into the club now, missing days of school as young as 12 years old, missing whole days, and 15-year-olds are coming in maybe twice a week," he said. "In my opinion it's just getting farcical."

I asked Joe Deeney, one of the youth coaches, about the wastage. "It's a long evening's work telling a load of boys that their dream's over," he admitted. After the training session I sat in the changing room with a 16-year-old called Frankie Musonda. I asked where he would ideally like to end up. "Somewhere in the premiership and hopefully internationally as well," he said. I asked what he thought his chances were. "I think if I work hard any of it's possible, really," he replied.

The idealism and ambition of the youth team contrasts with the attitudes of the seniors. For the older players, football has ceased to be a dream and become a job: "It's different for younger boys that have got more ambition, but it's all about paying bills at the end of the day," 31-year-old McNulty told me. By the standards of the academy, the senior players have already made it. Yet, at the same time, they have failed to make it to the big time. The exact hinge, the moment when the dream evaporated, when the Luton players realised that they had found their permanent level, was hard to ascertain. Barnes suggested late twenties as the tipping point.

Assessing the moment of realisation was also made harder by the talismanic faith some players had in certain success stories. I heard several mentions of Jamie Vardy, who moved from conference-side Fleetwood to Leicester City, a club that then gained promotion from the championship to the big time. Another touchstone was Grant Holt, who at one stage was playing part-time football for Barrow and working in a factory, before appearing in the premiership for Norwich.

Vardy and Holt's stories are powerful, but that they are memorable shows that they are rare. In reality, it is unusual to progress up from the lower leagues. Premiership players are often in premiership academies by the age of 14. When I asked the coaches about the key factor for success, they tended to offer a single answer: hunger. "Players can be a little less hungry," said Deeney. "You expect players to be as hungry as hell, but they're not, always . . . it's society now."

Britain's Crappest Town

I wanted to know what had happened to the bottom of English football in the time the money poured into the top, and Luton Town walked the exact line between those two worlds. In the 1980s, English football was troubled. Hooliganism and racism were rife, average top-flight attendance in 1985 was 19,563, compared to 36,695 in 2013/14. Still, back then, Luton Town played in the first division. On 24 April 1988, two goals by Brian Stein secured a 3-2 victory against London titans Arsenal in the final of the League Cup at Wembley.

In 1991/92 the team were party to the premiership pre-launch discussions. But they were relegated that season and later fell much, much further. Luton never had the opportunity to play in the new league they'd helped to design. Dominic Allan, an artist who has exhibited at London's Saatchi Gallery under the name "Dominic from Luton", attended the crucial away defeat at Notts County in April 1992 that sealed their fate. "I was 15 at the time," he remembered. "Men my dad's age and older just sobbing, sobbing because we'd been relegated from the old first division, now the premier league, but knowing that three, four months time from that day was the start of a new era in English football, and knowing that we'd missed out."

Luton spent much of the 1990s in the third tier, rising briefly in the middle of the next decade to the second. Between 2007 and 2009, the club was relegated three times in three seasons. In 2009, following a 30-point deduction for financial irregularities, they fell out of the league entirely, and spent the next five years in the feeder competition below – the Conference, a division that includes semi-professional clubs. Last season, in April 2014, Luton finished as Conference champions, ending their long exile. When I visited, they were beginning their first spell back in the football league. Hopes were high. But they were still in the fourth tier going into that October weekend: 71 places below Manchester United, 74 below Arsenal and 77 below Chelsea, then top of the Premiership.

In the same period, Luton had become a byword for urban mediocrity. In 2004, more than 20,000 people voted Luton "Britain's crappest town" in an online poll. Luton Town's nickname – the Hatters – riffs on the town's onetime reputation as a centre for millinery, but its industrial sector – later dominated by the carmaker Vauxhall – has diminished. Meanwhile, Luton has experienced massive South Asian immigration. There is evidence of radical Islam. In recent years, a constellation of serious jihadists has emerged with connections to the town, Including Taimur Abdulwahab al-Abdaly, who blew himself up on a shopping street in Stockholm in 2010, and three men who died fighting for the Taliban.

Predictably, there was a counter-surge to the radicalism. Luton gave birth to the English Defence League, an organisation formed in 2009 that marched against perceived Islamification of the nation. Tommy Robinson, the young demagogue who founded the league, is a life-long Luton Town fan, a man who forged much of his identity on the terraces at the club's stadium, Kenilworth Road. "Everyone I know, I know through going to football," he would tell me later. "All of my friends, my friendships, everything around us, has been based around Luton Town football club." Kenilworth Road sits in the heart of a Muslim area, but the fans are mostly white.

Release

Spending time with the Luton players, I saw that much of football success is dependant on human relations – a manager liking you, a scout happening to be there when you happen to play well. Someone had to give Grant Holt and Jamie Vardy their breaks. That is why coaches speak about "hunger" – it is acceptable code for the real mixture of luck, happenstance and human intercourse that is required alongside skill and determination.

The other key word is "released".There is a brutal winnowing of talent between 16 and 18, but still many of the senior Luton players have experienced rejection from other clubs. Mark Cullen: released by Hull. Stephen McNulty: released by Liverpool. It was clear that the experience was potentially devastating. Some of the players struggled to articulate it, but one in particular had transformed it into a kind of art.

Matthew Robinson was born in Leicester in 1993, he spent his teenage years on the books of premiership club Leicester City. At 18 he was released. But Robinson had a different way to express his disappointment. The first time I met him, out on the training pitches, he explained that he was the best rapper in the football league. One afternoon at the training ground he performed for me for part of his track, The Only Way is Down:

"When you're in pursuit of perfection you ain't used to rejection, But that shit will look different from a neutral perception, It's the fear of feeling inferior, sometimes your face really don't match the interior, Sincerely, the kid who weren't quite up to par, That's the thoughts of astronauts who never quite touch the star."

One evening, after a game, Robinson saw me walking to my hotel. He gave me a lift in his Renault Clio. On the back seat rested the cover for his new record. When I came back to Luton a month later, he was gone – loaned out to Kidderminster Harriers. At the bottom of English football, the future is never secure.

Read the full behind-the-scenes story of life at Luton Town Football Club in Simon Akam's ebook, The Club, available now through Newsweek Insights.