There are bodies everywhere, and rumors of so many more.

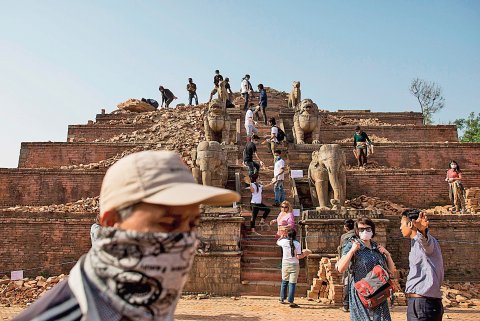

That's one of the major reasons people are fleeing Kathmandu by the hundreds of thousands. The broken streets of Nepal's capital have emptied as so many of the young men and women (mostly men) who left their far-flung rural villages to make their fortunes here are now going back home. "There are corpses in the buildings that are beginning to smell," says Bhaba Thami, who lives in the city with his wife and two children. "It's scaring people."

Many of the city's fallen buildings have still not been fully exhumed after a magnitude-7.8 earthquake and its many trailing tremors started leveling Kathmandu on April 25, so no one knows how many more people are buried in the rubble. In the neighborhood of Swayambhu, people say, Mass was being held in a church when the earthquake hit. The minister had the doors shut and told his congregation to pray, but the building collapsed anyway, crushing everyone inside. The bodies of the supplicants are still there. The story may be apocryphal, but the horror behind it is palpable and pervasive.

There are other fears too. Waterborne diseases could soon spread, just as cholera cut a lethal swath through Haiti following the 2010 earthquake there. Theft and looting are brought up regularly as more prosaic concerns, as are potential food and water shortages. "It's suffocating at the moment," says Thami.

It's one reason he has decided to go back to his ancestral home in Suspa-Kshemawati, a village development committee in the Dolakha district, a mountainous region about 90 miles from Kathmandu. His father and sister are still there; he spoke with them after the quake and knows they're alive and uninjured. He also knows the house he had been living in with his family is a pile of bricks and dust. He wants to ensure that his father and sister have a place to stay, food to eat and water to drink, so he'll leave his wife and two children in Kathmandu for now. He will also be riding up those treacherous roads as a sort of emergency relief worker, taking notes on the damage in the far-off village and returning to Kathmandu in a few days to report to a makeshift group organizing aid. The vital information he collects will help determine what gets loaded into the next truck making this perilous, tortuous trip—tents, or food, or doctors.

The day Thami and I head out from Kathmandu, 600,000 people are already on the same road. This is one instance in which the Nepalese government, overwhelmed by this tragedy, has stepped up in a significant way: It has provided free transportation out of the city to the villages. But that means there are lines a half-mile long at the bus stops, and on the road, buses loaded to the ceiling with the displaced swing through hairpin turns. Even the rooftops of the buses are packed with people of all ages clutching to the railings to keep from falling off as their bus swerves around massive cracks in the road. Our much more nimble car skirts these blockages with relative ease, despite being loaded down with four people and bags stuffed with food, blankets and clothing.

I'm told repeatedly that this is the most beautiful time of year in Nepal—the valleys are verdant, the flowers are blooming and the monsoons are still waiting in the wings. But what would normally be spectacular views are marred by wide, ugly gashes of destruction. Brick-and-timber roadside shops and restaurants and family homes nestled in the terraced hillsides have been flattened.

After four hours of driving, we stop in Khadichaur, a small town close to the border with China in the Sindhupalchok district. We pick up Rastra Bhusan Khadhka, who went to high school with Thami and is traveling back to his village to check on his handicapped father. We also buy rolls of plastic sheeting, which we will give to the villagers to use for shelter. Here, as in every town and village we've passed through, almost every building has been crushed. But we find a restaurant serving lentil soup and rice, curry chicken and soy meatballs.

As we eat, the owner tells us that throughout the area, the dead are trapped in cars and pinned to the mountainside by bikes that tumbled off roads when the quake hit. They remain unclaimed, he says, because no one will climb down a hillside that appears to be on the verge of collapse. Those fears are well-founded: The roads below these Himalayan foothills (though that name is a severe understatement for an area that in places reaches 13,000 feet above sea level) are littered with fallen earth, ranging from mudslides to boulders as big as a Honda Civic.

As we pass village after village, we rarely see a building that is still standing. In the district headquarters of Charikot, a government official tells me 95 percent of buildings are uninhabitable.

As our SUV climbs and climbs, a mist envelops us, and the pitch of the mountainside makes the telephone wires into the valley appear to trail off into the nothingness. On both sides of the road, we see hundreds of people picking through the remains, searching for some small, unbroken piece of their former lives. Their eyes mostly appear to be focused on some middle distance, to some place or time beyond all this death and debris.

Disaster Matchmaker Service

Money is being wired into Nepal from all corners of the globe in every currency imaginable. Planes carrying rescue teams speaking two dozen different languages and loaded with sundries meant to sustain the newly homeless circled for hours before being turned away because the single runway at the Kathmandu airport was logjammed. Do-gooders arrived immediately after the earthquake with the best of intentions but the least of plans—and no place to stay, no contacts or translator and no idea how to even feed themselves.

The fresh-off-the-boat aid workers "were not ready for the reality on the ground," says Jacob Rinck, a Nepal-based sociocultural anthropology student working on his Yale Ph.D. "They didn't know what was up and what was down." The United Nations is operating the country's largest official coordination program, and Nepal's Ministry of Health and Population is asking doctors and health worker groups to register with it and then take its instruction on where to go.

That's how it's supposed to work, "but in reality, it's a cluster-fuck," says Amit Aryal, an adviser to the ministry and a health systems expert. "Some don't go where they are assigned to go. Some get lost. Some don't report to the district offices." In response, Rinck and his wife, Aditi Shrestha, along with Dawa Stephen Sherpa, Parakram Singh Yonzon and other like-minded citizens, have created a sort of disaster matchmaker service. Based in Yonzon's Tibetan furniture store, Samsara Studios, they figure out who can supply goods and services and who needs them the most, then put them together.

The Samsara Studios volunteers are frustrated by the government's slowness, ineptitude, graft and corruption. In the early days of the crisis, says Yonzon, the government was charging huge taxes on imported tarpaulins—unless those imports went through government channels instead of through nongovernmental groups like the U.N. "The government is trying to get things under their control," he says, but is also hobbling the efforts of aid groups and individuals to assist the estimated 8 million people who so desperately need help.

On May 3, the government issued a press release stating that this was not the case: "We also appeal to everyone to not fall prey to any confusion that has been created through news media's false/incorrect/illusionary/rumourous reporting of relief material not being provided with custom exemption, now and then, and their import being made complicated." But there continue to be daily reports of relief materials piling up in the Kathmandu airport, unable to get through customs.

"We never have high expectations for the government," says Thami. "Political leaders will distribute to their own family and people first." There is a historical precedent for this cynicism: After a smaller earthquake back in 1988, blankets donated by aid agencies were later found in the homes of officials and in warehouses and closets of businesses that had volunteered to distribute them.

The Samsara Studio team is attempting to build distribution channels that draw directly on the knowledge and resources of locals and, therefore, do need to not rely on any government agency. Pragya Singha, whose family owns real estate in Kathmandu, was frustrated that the poorest villages were receiving the least help, so she packed up her car with supplies and hired a driver to bring them out to the village of Taruka, the ancestral home of some of her staff members. Robin Shrestha asked his brother-in-law, who owns a pharmacy, to send all the supplies he could to the Ghorka district where Shrestha is from—and send him the bill. Ana Tara Edwards's family founded Tiger Tops, a trekking company that has hundreds of tents and other useful goods in their storage rooms. She called her brother, who now runs the company, and told him, "We're letting everything go."

'Unbelievably Corrupt'

It takes about six hours to cover the 90 miles of our trip, and as we pull into the village, nightfall is hovering over us. When our passenger Ram Thami sees his house for the first time, he cries. (He is no relation to Bhaba Thami, though they are both part of the same ethnic group; the Thami widely populate this part of the country, and many of them share the same surname.) The roof has caved in, and huge chunks of the walls are gone; you can see clear through from one side to the other. The kitchen and bathroom are destroyed—no small loss in a village hours from any place selling construction supplies. "I built this house myself," he says. "It's stood for 20 years. [The earthquake] set us 10 years back again." His wife and four children, as well as his aging mother, will sleep outside tonight, and the next night, and into the foreseeable future. One of his daughters, the village seamstress, shows us her sewing machine, the metal crumpled like a discarded ball of paper.

There are no longer homes for people to sleep in, so the villagers in Suspa-Kshemawati have set up makeshift camps in which they now eat and sleep. The families who have been able to recover some of their possessions have their own tent complexes with wooden posts, tarpaulins and colorful rugs and woven cotton sheeting. Those who could not huddle under sheets of corrugated metal pulled from the piles of rubble that were once their homes. There is still food here, but it's running out. Most of the food that was in homes was destroyed or is now tainted, and many people are buying provisions on credit from the two village shops. No one has any idea what will happen when the shop shelves are bare.

"I managed to buy some food in Charikot," says Bir Bahadur Thami, Ram's brother. "We are sharing with all our relatives. But there is a black market that has made all the prices higher. I am worried of a future crisis."

As we speak, the earth shudders. Standing out here under the wide moonlit sky, I know there is nothing that could crush me. And I am already on the ground, so there is nowhere to fall. But the fear around me is more existential. In this part of the planet, where the tectonic plates long ago smashed together and shoved the earth so far skyward, it seems just as likely that at any moment things could reverse course and rip open a gaping hole that would swallow us all.

It is now five days after the initial quake, and we are the first people to reach here from Kathmandu. There has been no communication with the outside world, no visits from international aid groups or government assessors; everything they know about the disaster is from firsthand experience or word of mouth. "We're looking for a radio," says Yadav Raj Thami. People say the local police have been nonresponsive, and they have had no means to contact anyone else. "We called the police to record the dead," says Bhim Thami. "But they ran away, scared. We are hopeless that the government will help."

The sentiment is common in Nepal, from sustenance-farming villagers to international aid executives and foreign legislators. "The Nepali government are unbelievably corrupt, slow-moving and frustrating," says Macartan Gaughan, who is on the board of directors for the Umbrella Foundation, a nonprofit that works to reintegrate illegally trafficked Nepalese children back into their families. Gaughan says that getting anything done requires bribes and backroom handshakes. When the Umbrella Foundation wouldn't play along, he says, its project agreement was stalled for 18 months.

Earlier this year, a committee of the British Parliament wanted to cut off aid to Nepal, which "suffers from poor governance, and corruption is endemic," said committee chairman Malcolm Bruce. "If Nepal is to become less corrupt, improvements in governance and a change of culture have to be made to state institutions."

This widespread corruption is one reason the earthquake was so devastating. "Our own people have destroyed Kathmandu," says Robin Shrestha, by building quickly and with little thought to safety. Though new construction must ostensibly meet earthquake safety standards, there is little oversight. Robert Piper, former resident coordinator for the U.N. in Nepal, told the Thomson Reuters Foundation in 2011 that "in a place like Kathmandu, a new building pops up every day which has not been built to code."

Even the local government officials believe the state isn't moving fast enough after the quake. "Ninety-eight percent of places are destroyed here," says a local representative in Dolakha who did not want to give his name. "The government has been very slow. We're angry. If we don't get [help] in time, we'll strike."

The failures of the government are unsurprising given its rich and recent history of disorder. The country is less than a decade removed from a civil war, instigated by a Maoist uprising, that ran from 1996 to 2006. One day in 2001, the entire royal family was killed; it is believed that the heir to the throne at the time, Prince Dipendra, murdered nine members of his family, including the king and queen, before turning the gun on himself. At the end of the civil war, the country began what has been a painful and fitful transition from a constitutional monarchy to a federal republic. But the constitution has been pending now for six years because of internal strife.

Meanwhile, as the International Crisis Group wrote in a 2010 report, the power elite has "survived the conflict surprisingly unscathed, and unreformed. This is partly because its own raison d'être is not serving citizens so much as servicing the needs of patronage networks and keeping budgets flowing and corruption going. The state is dysfunctional by demand."

Rajeev Shah, a member of Nepal's Constituent Assembly, says the flak the government is now getting is unfair and counterproductive. "With our resources we are doing our best," he says. "Distrusting the government right now is not the solution. We need to work together." When I press him about the citizen concerns of misallocated funds, he says, "People don't trust the prime minister's Disaster Relief Fund, but what can you do by yourself? Only a government can handle a disaster of this scale." Shah says he is working with a team of legislators to bring refugee camps into each of the affected districts, but adds, "We can't afford door-to door-service."

A major obstacle for even honest efforts is the unavoidable fact that travel through Nepal has always been difficult. Its inaccessibility has been both a boon and liability: It kept the country from ever being conquered by any of the European superpowers that carved up Asia in the 19th century and has enabled local ethnic groups to retain their unique cultures. This is a large part of what makes Nepal so special—Kathmandu, to this day, remains a byword for the wonders of the exotic, the remote, the unexplored.

But that geographical and cultural isolation also had debilitating consequences. Unlike, for example, India, Nepal's close neighbor to the south, there is no legacy of British road building or rail infrastructure. Nepal has only 3,007 miles of paved roadways and just 37 miles of railways, putting it 132nd and 129th in the world, respectively—and the country has the world's 42nd largest population and 94th largest land area. In other words, there are too many people who have too far to go, and no good way to get there.

"[Delivering aid] was always going to be a logistical problem because of the topography," says Orla Fagan, one of the United Nations's regional public information officers in Kathmandu. At the same time, she says, "no one will be forgotten. There won't be any village that won't be assessed."

Until the U.N. gets to those villages, though, it's up to private citizens like Bhaba Thami and Robin Shrestha to do the job. After they speak with the villagers and take their careful notes, we all make our beddings in a tent and eat rice dhal for dinner. Another small tremor shakes us as we sip rice wine from tin cups. Ram's sister, already a little tipsy, tells me about her experience during the quake. The first thing she noticed was children falling down. She immediately grabbed them and ran out of the house. "We didn't think there would be a life after," she says. But then she takes my head in her hands, pulls me close and says, "but we have hope."

And right there is another way Nepal is like no other place, even in the midst of pulverized buildings and rotting corpses. In most of the world, the phrase "life goes on" suggests resignation, brutally diminished expectations. The Nepalese, though, address change head-on and are usually congenial and calm. Ram's daughter says she wants to fix her sewing equipment as soon as possible; his son constructs a platform bed for the family's guests (including me) out of plywood and nails recovered from the rubble; a nephew, 17-year-old Sagar Thami, is mostly upset because his school is closed. "I will gather the other students and strike," if classes don't resume soon, he says.

During our long drive to get here, there were plenty of sad sighs and sucking of air through teeth as we passed fallen villages. But there was just as much joking and laughter. When we arrived at Suspa-Kshemawati, the first thing we saw wasn't tears, and the first things we heard were not complaints. It was the music of a wedding procession.

Soldiering Up

In Charikot, all the windows of the district government building are smashed, but you can't blame that on the earthquake. Earlier this week, people who were angry because they felt their plight was being ignored descended on the building, hands balled into fists. They picked up rocks from the parking lot and hurled them through those windows. When the protesters got inside, they smashed tables and chairs.

The government officials here are, quite reasonably, uneasy, and they are soldiering up: Nepal army units mill about, shining their boots and cleaning their weapons. "Some people are not getting what they need and are very tense," says Ramesh Paudel, an inspector with the Nepal Armed Police Force. He's sent some soldiers to guard the city's bank, and others will escort a convoy of food being delivered today.

"We are planning to distribute supporting materials," says Resham Kandel, a local development officer. The next day, local officials will give out $20 to each adult villager they can find. But, he tells me, they've gotten nothing from the central government, despite constant pleas. "We need support in massive quantities," he says.

We're interrupted by the sound of a helicopter overhead. We step outside and look out over the hills. Until today, Nepal has been racked by intermittent, driving rains, which made all those forced to sleep outside, often without cover, even more miserable. Today, though, the clouds have cleared, and I see for the first time the ice-capped Himalayas.

The helicopter is bringing back 15 children from a village deep in the mountains, normally a five-day drive from here. Their village sits below Tsho Rolpa Glacier Lake, and officials determined that there's a chance the lake bed was compromised during the earthquake, so the small village could be drowned by a massive landslide the next time the earth shudders. The chopper was unable to carry out the 70 adults who live there, including the parents of these children, and won't be able to return for them anytime soon.

Travel to Nepal and accommodations there were provided by the International Reporting Project.