In the opening scene of Patton (1970), the film's namesake addresses a sea of troops about to be hurled onto World War II's front lines in Europe and North Africa. General George S. Patton says, "Now, I want you to remember that no bastard ever won a war by dying for his country—he won it by making the other poor, dumb bastard die for his country."

The film Good Kill, which comes out this week, depicts a lieutenant colonel delivering a similarly rousing speech to a group of recruits about to enter combat. Only this time it's with drones. "Ladies and gentlemen," he says, "the aircraft you're looking at behind me is not the future of war; it is the here-and-fucking-now."

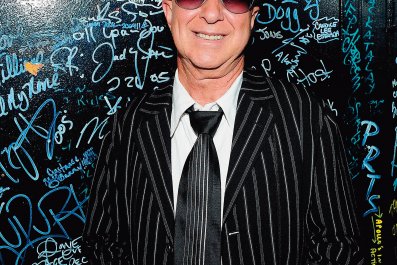

The movie, written and directed by Andrew Niccol (Gattaca, Lord of War), provides a harrowing look at warfare's newest frontier through the eyes of a fictional drone pilot. Major Tom Egan (Ethan Hawke), a former Air Force pilot yearning to fly again, spends 12 hours a day fighting militant groups like the Taliban from a dark, air-conditioned bunker in the Nevada desert—more than 7,000 miles away from the battlefield. Through prolonged close-ups on his computer screens, the audience is complicit, forced to watch as his strikes claim lives. When the camera turns, the audience sees Egan gradually unraveling from the stress. Joystick in hand, he surveils and strikes targets seen on a computer screen, racking up casualties. And then, after his shift, he trudges back to his home in Las Vegas, where his wife (January Jones), children and the challenges of domestic life await him.

From World War II to contemporary conflicts, war films often highlight the humanity of soldiers, helping to connect civilians in the audience to the people and wars they once understood only in the abstract. Good Kill adds to this long cinematic tradition within the context of the U.S. drone program, a little-seen world filled with men and women at the forefront of modern warfare. "You can't say you're anti-drone," Niccol tells Newsweek. "It's like saying you're anti-Internet."

"The really exciting thing about working with Andrew [Niccol] is that he doesn't really see this from a left-wing point of view or a right-wing point of view," Hawke says. "He's kind of coming at it as a humanitarian and a scientist."

So how accurately does the film depict the lives and thoughts of these modern fighters? Newsweek reached out to a former drone operator, Brandon Bryant, to gauge how realistic the movie's portrayal is and discovered that, in August 2013, early on in Good Kill's production, he was contacted by a producer, who asked for his insights. Bryant critiqued an early version of the script, told his service stories and answered questions. But a few weeks in, he says, the producers became unresponsive.

This is nothing new to Hollywood insiders, who are used to the slow pace and false starts of independent filmmaking, but Bryant thinks the "snubbing," as he refers to it, was because of a disagreement regarding one element in the script. Or rather, an element noticeably absent from it: the psychological impact of remote warfare on drone operators. "The psychological aspect is the most important part of this kind of film," says Bryant. "Because what we've done is taken the warrior from the battlefield where...they're no longer with their comrades."

In 2005, Bryant was a University of Montana student struggling to pay his tuition and searching for any way out of Missoula. He agreed to give his friend a ride to a nearby Army recruiting office that summer and weeks later signed up to join the Air Force. After several months of testing and training at Lackland Air Force Base in Texas, Bryant was assigned to a windowless bunker on the periphery of Las Vegas, just like Hawke's character in Good Kill. His job was to guide missiles to their intended targets via laser. He hated the work instantly, but, also like the film's main character, Bryant knew he had to tough it out. In just six months during 2007, he says, he killed 13 people with four shots—some targets, others "collateral damage."

He can recall every devastating detail of his first strike. Three men with rifles were walking along a road somewhere in Afghanistan; the two in front looked as if they were having an argument, while the third wandered a little behind them. Bryant says he had no idea who the men were, only that they were targets. Command ordered his team to aim a missile at the two men in front instead of the one in the back, as "two is better than one."

When the smoke cleared, a crater appeared on Bryant's screen, littered with the body parts of the two men. The third man lay on the ground, missing part of his right leg. "I watched him bleed out," Bryant recalls. The third man's blood, which on Bryant's screen appeared white in infrared, drained from his body, pooled on the ground and cooled. "After a while, he stopped moving, and he became the same color as the ground."

The horrors of his work soon wormed their way into Bryant's subconscious. "I used to have a lot of trouble sleeping," he says. "I just hated seeing my work when I closed my eyes." This aspect of the job gets a nod in the film: As Egan retreats into himself and those he loves drift further away, he seeks comfort in vodka. Prolonged depression gives way to rage—Egan gets physically violent with his wife and angrily throws a bottle of liquor after a cashier makes a joke about his flight suit.

In 2011, nearly six years after joining the Air Force, Bryant turned down a $109,000 bonus and left. Upon exiting, he was presented for the first time with a report on his accomplishments: He was associated with 1,626 kills. "I felt sick to my stomach," he says. "Civilians were being killed because leadership didn't care…. All they were doing was racking up tallies for their promotions."

Bryant's guilt weighed heavily on his conscience. On a trip to Best Buy in late 2011, he used his military ID while paying for a video game. A young man behind him noticed it. "You served in the military? So did my brother. He served in the Marines and he killed, like, 30 people. How many people did you kill?" In front of a store full of people, Bryant responded, "If you disrespect the taking of another person's life ever again, I will find you and kill you in front of your family." He was asked to leave the store.

It was after Bryant begrudgingly told a therapist this story that he finally agreed with her diagnosis: he had post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

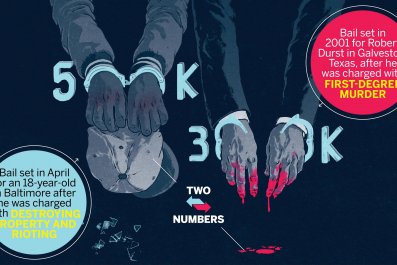

The issue of PTSD in drone operators is controversial. To someone outside the military, it might seem that a distinction should be made between those in combat who are on a conflict's physical front lines and those operating on its technological front lines. But does such a distinction extend to remorse or guilt? Or to the difference between whether the blood that a soldier may feel on his or her hands is there literally or just on a computer monitor?

Madeline Uddo, a psychologist and team leader of the PTSD clinical team at the Southeast Louisiana Veterans Health Care System, says PTSD can be diagnosed if a certain number of symptoms outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders—the guide used in psychiatry to diagnose mental disorders—are present. She notes that the manual's fifth edition seems to cover the experience of drone operators. Furthermore, a Defense Department study from 2013 found that drone pilots experience many stress disorders, including PTSD, at the same rate as aircraft pilots.

Hawke and Niccol say that soldiers like the fictional Egan and the very real Bryant are essentially test subjects, and that what the military asks of them has "never been asked of a soldier before." It's an admission that Good Kill is in uncharted territory, but they avoid saying that Egan has PTSD, although Niccol calls what Hawke depicts in the film "an approximation" of PTSD.

According to Zev Foreman, a producer on the film, the creators were determined to leave Egan's diagnosis open-ended so the audience is able to better interpret how it feels about the drone program. Or, as Foreman puts it, "[we're] not making a statement particularly about anything while opening up a discussion about everything."

Still, Bryant maintains that the filmmakers, in telling a drone operator's story, have a responsibility to weigh in on the remorse that many of them face, something he feels Good Kill largely fails to do. "I wanted [them] to make a powerful movie, not just an entertaining one," he says. "[They] wanted to make something akin to Top Gun with drones…. They're doing what our society does—marginalizing the traumatic effects of personal experiences."

While this back-and-forth could be chalked up to an outsider not understanding Hollywood's rules, it indicates a bigger issue: Although troops can perform their duties 7,000 miles away from battle, that doesn't mean they're safe. And although drones allow us to see into any corner of the world at any time, when it comes to the psychological effects this type of fighting has on our soldiers, we're flying blind.

Bryant is currently in an inpatient program designed to help him cope with his PTSD. "When I go back to those memories and my emotions get high," he says, "I feel rage or extreme depression. It's helping me manage those emotions."