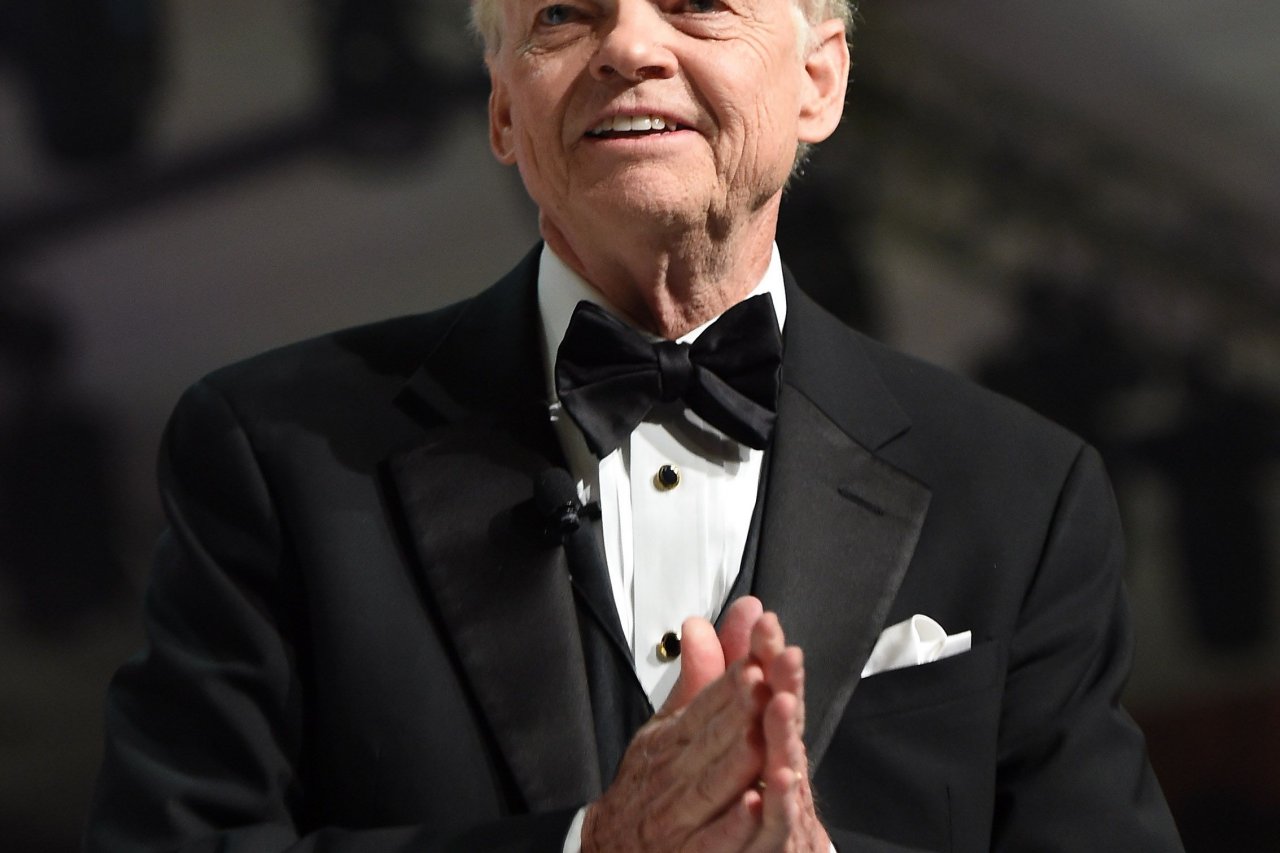

A long time ago, when he was a towhead lad in Carthage, Illinois, Jimmy Walker collected autographs. Then he moved on to collecting people. Famous ones, mostly. "Reggie Jackson was my best friend in college," Walker, a boyish 70, will tell you, and, "I was a pallbearer at Peter Maravich's funeral" or "We flew over to Italy on Mark Cuban's plane.…"

Movie stars. Musicians. MVPs. Walker drops the names of A-listers incessantly, but he does so without pretension. "You know what ego stands for?" the devoutly religious Walker will ask. "Edging God out." And yet there he goes: "Michael Jordan came to the house for dinner and Glen Campbell performed," he says. "Billy [Crystal] told me that Donald [Trump] wanted me to phone him.…"

Walker peddles life insurance policies—he sold his first in high school—but his raison d'être for the past three decades has been philanthropy. And if he just happens to befriend every celebrity on the planet while raising tens of millions of dollars, so be it. "When I go to a dinner party at Jimmy's house," says his older brother Gary, "I'm the only person there that I don't know."

The A-List Honey Trap

A hotel ballroom in Phoenix in late March. An impressive lineup of musical talent: Blake Shelton, Kelly Clarkson, Josh Groban, Ronnie Dunn and the host, Reba McEntire, who is emceeing tonight on her 60th birthday. The evening ends with a rendition of the girl-power anthem "I Will Survive," performed by Gloria Gaynor herself. The musical director is legendary producer David Foster, a 16-time Grammy winner who met Walker at the Grammys in 1996.

The artists perform pro bono. The 1,300 or so guests paid from $1,500 to $25,000 to attend. During the auction portion of the festivities, Bob Parsons, founder of Scottsdale, Arizona-based GoDaddy.com, bid $1 million on a dinner at McEntire's house. Walker's charity, which primarily benefits Parkinson's disease research, will reap approximately $7 million this evening. "This was our 21st Fight Night," says a bleary-eyed Walker the next morning of an event that over the years has distributed approximately $65 million to charities. "Every year, David Foster says to me, 'Maybe this should be our last year.' He's said that 18 times now."

The 21 years of Celebrity Fight Night (in its nascent days, celebs boxed wearing oversized gloves) in Arizona have attracted a salmagundi of celebrity: giants (Quinton Aaron from The Blind Side) and dwarfs (Verne Troyer, a.k.a. Mini-Me); the stars of Raging Bull (Robert DeNiro) and Bull Durham (Kevin Costner); Forest Whitaker and Forrest Gump (Tom Hanks); a woman who scored a perfect 10 (Mary Lou Retton) and a woman who rated a perfect 10 (Bo Derek). If all the world is connected by six degrees of Kevin Bacon (who has also attended), we may need only two degrees of Jimmy Walker.

"There are 7 billion people in the world," says former Louisiana State University basketball coach Dale Brown, "and Jimmy probably knows half of them. He's probably having coffee with Pope Francis right now."

While the altruism of the aforementioned celebs should be above reproach, Walker does dangle a honey trap at Fight Night. It is a lure that has snared eight Super Bowl MVPs as well as arguably the greatest figures ever in baseball (Willie Mays), basketball (Kareem Abdul-Jabbar), golf (Jack Nicklaus), hockey (Wayne Gretzky) and the Olympics (Michael Phelps): "I got to meet Muhammad Ali," gushes 18-time Grand Slam singles champion Chris Evert, an attendee, when asked to describe the highlight of the evening. "That was the thrill of my life."

The Contagion of Benevolence

This is a typical Jimmy Walker story: At the St. Regis Hotel in New York City a few years ago, former Phoenix Suns general manager Jerry Colangelo, Walker and their wives were on a pre-Christmas shopping excursion. They were standing in the lobby when Colangelo noticed Andrea Bocelli, the world-famous Italian tenor, stepping into an elevator. "I said, 'That's Andrea Bocel—,'" recalls Colangelo, "and before I could finish the sentence, Jimmy had already bee-lined over there."

Bocelli is blind, so he could not know that Walker had stuck his arm between the doors of the elevator to halt its progress. "You and I have a friend in common," said Walker. "David Foster."

Before Bocelli could exit the elevator, Walker had told him about his annual charity event and then dropped the name that always closes the sale: "Muhammad Ali."

Two days later, Bocelli was in Arizona, entering the home of the Greatest. He was dropping to his knees, supplicating himself before Ali. Singing "Happy Birthday" to Ali's wife, Lonnie. That spring, Bocelli performed at Celebrity Fight Night. One year later, he hosted the first international incarnation of the event, performing along with John Legend, Jennifer Lopez and Lionel Richie. Guests who paid $60,000 per person flew over on Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban's private jet and basked for five days in Tuscan splendor. "We honored Sophia Loren and George Clooney," Walker says proudly. "It was George's first public appearance with his future wife, Amal."

Celebrity, particularly in the sports genre, has been a lifelong obsession of Walker's. As a boy, he would contact baseball players, as many as a dozen per week, requesting autographs. "I would tell them that I was sick or that my mom wanted to marry them," says Walker, whose mother was already married to his father. "Satchel Paige wrote back with an autograph and a request to be reimbursed for his 2-cent stamp."

In the early '60s, Walker landed a basketball scholarship to Arizona State University, where he was a teammate of "Jumping" Joe Caldwell, who would win an Olympic gold medal in 1964 and was both an ABA and NBA All-Star. In Tempe, Walker also befriended another ASU jock. "I saw Reggie [Jackson] walking on campus and thought, 'He's either the cockiest guy or the most talented guy around,'" recalls Walker, who sold Jackson a $1 million life insurance policy, and introduced him to his older brother Gary, who was Mr. October's agent throughout his Hall of Fame baseball career.

If there is a patient zero to the contagion of benevolence that is Jimmy Walker, it's Jackson. In 1977, the two of them, along with Gary, purchased a World Team Tennis franchise, the Phoenix Racquets. Walker knew little about tennis, but he did know the most popular name in the sport. "I flew down to Fort Lauderdale and met with Jimmy Evert [Chris's father and coach]," says Walker. "I convinced him that this would be good for his daughter."

Evert signed with the Racquets. "Jimmy was deeply religious and into his family," recalls Evert, who at the time was the world's No. 1 player. "He would suggest we attend Bible study with him. I went once, and I left with a wonderful feeling of calm. That night, I lost to a girl that I never lost to. I never went again. I realized that I needed to be a little bitchy to win."

World Team Tennis would fold within two years, but not before Walker befriended two other neophyte sports owners: Robert Kraft, who has since won four Super Bowl rings as the owner of the New England Patriots; and Jerry Buss, who won 10 NBA championships as owner of the Los Angeles Lakers before his death in 2013. One night, Walker was doing his Zelig act before a Lakers game. Buss was seated at a table dining with Sammy Davis Jr. and Muhammad Ali. Like a shark circling his prey, Walker surveyed the table and then pounced. "Muhammad, I'm a friend of [former heavyweight boxer] Earnie Shavers," he said. "Earnie really loves you."

"If he loves me," replied Ali, "how come he hit me so hard?" And a friendship between Walker and the Greatest, who lives in Scottsdale, was born.

Walker's office is situated on Camelback Road. ("Have you seen his wall of fame?" asks Dale Brown. "I think the only celebrity he's missing is Mussolini.") It has long shared a parking lot with the Ritz-Carlton, the preferred lodging for most visiting NBA franchises. Once, when the Philadelphia 76ers were staying there, Walker had the idea to leave his black Mercedes with the hotel's valet for the personal use of future Hall of Famer Julius Erving. Dr. J gladly accepted the keys. As would Michael Jordan a few years later.

Walker launched Celebrity Fight Night in 1994, and the event enjoyed modest success its first two years. But then Walker hatched a grander plan. He phoned Abe Lieberman, a Phoenix-based neurologist who also happened to be Muhammad Ali's physician. Walker pitched Lieberman on the idea of using his patient, perhaps the world's most recognizable figure, as the star attraction of his charity event. Instead of faux boxing matches, the event would shift toward musical entertainment. And almost all of the proceeds would benefit the construction of a Muhammad Ali Parkinson's Center—which has come to pass. "We used $6 million to build the center in 1997," says Lieberman, "and now we are staffing six salaries...[and] have about 10,000 patient visits per year."

Much of what Walker tells you, such as that he wakes up at 2:30 a.m. each weekday and reads the Bible, strains credulity. But it all checks out. He really was a pallbearer at the funeral of Maravich, whom he'd met through former Phoenix Sun Paul Westphal. Michael Jordan, along with former North Carolina Tar Heel James Worthy and their coach, Dean Smith, really did come to dinner at his home when Walker was trying to establish a drug rehabilitation center associated with Walter Davis, a favorite Sun and Tar Heel alum.

"I tell Jimmy all the time that he invented networking," says Colangelo, who met Walker just three weeks after moving to Phoenix in 1968. "You know the phrase 'Out of sight, out of mind?' That phrase has never entered Jimmy's mind."

Shaquille O'Neal, who is also a client of Walker's, refers to him as "a low-level botheration" and "the Big Contact." Everyone who knows Walker says the same thing: He has no shame, but he's never asking for anything for himself. "I've always made it a point not to be friendly with people who sell insurance," says Billy Crystal. "Jimmy came over once at a Clippers game and introduced himself. He kept talking and talking. He knew he had the hook in the gill of the fish. Not the mouth, but the gill."

Nevertheless, Crystal bought a life-insurance policy from Walker, became a regular at Celebrity Fight Night (no one ever did a better impression of Muhammad Ali, after all) and recruited Robin Williams, Jim Carrey and Tom Hanks to join him. "Some people you are leery about. You know, what's your angle?" says McEntire, who has been the emcee at Celebrity Fight Night the past 10 years. "But Jimmy is so pure. He has a heart of gold."

A week or so after this spring's event, the Arizona Republic ran a story that challenged that testimonial. It reported that in 2013 the Celebrity Fight Night board unanimously voted Walker a $600,000 bonus and, for the first time, awarded him a salary.

Walker's compensation became a big deal in the Valley of the Sun for about one week. Then GoDaddy's Parsons wrote another check for $1 million, this one to cover Walker's compensation for the next five years.

Meanwhile, the man who collects people will continue to collect donations by collecting people.

"We've got our second Fight Night in Italy with Andrea Bocelli scheduled from September 9 through 14," boasts Walker, his eyes beaming. "We just signed Tony Bennett. And we are taking a one-day excursion to the Vatican. Andrea is friends with the pope."

Is the world's most rabid collector of celebrity pals about to add Pope Francis to his Rolodex?

"Well," says Walker. "We're not making any promises, but…"