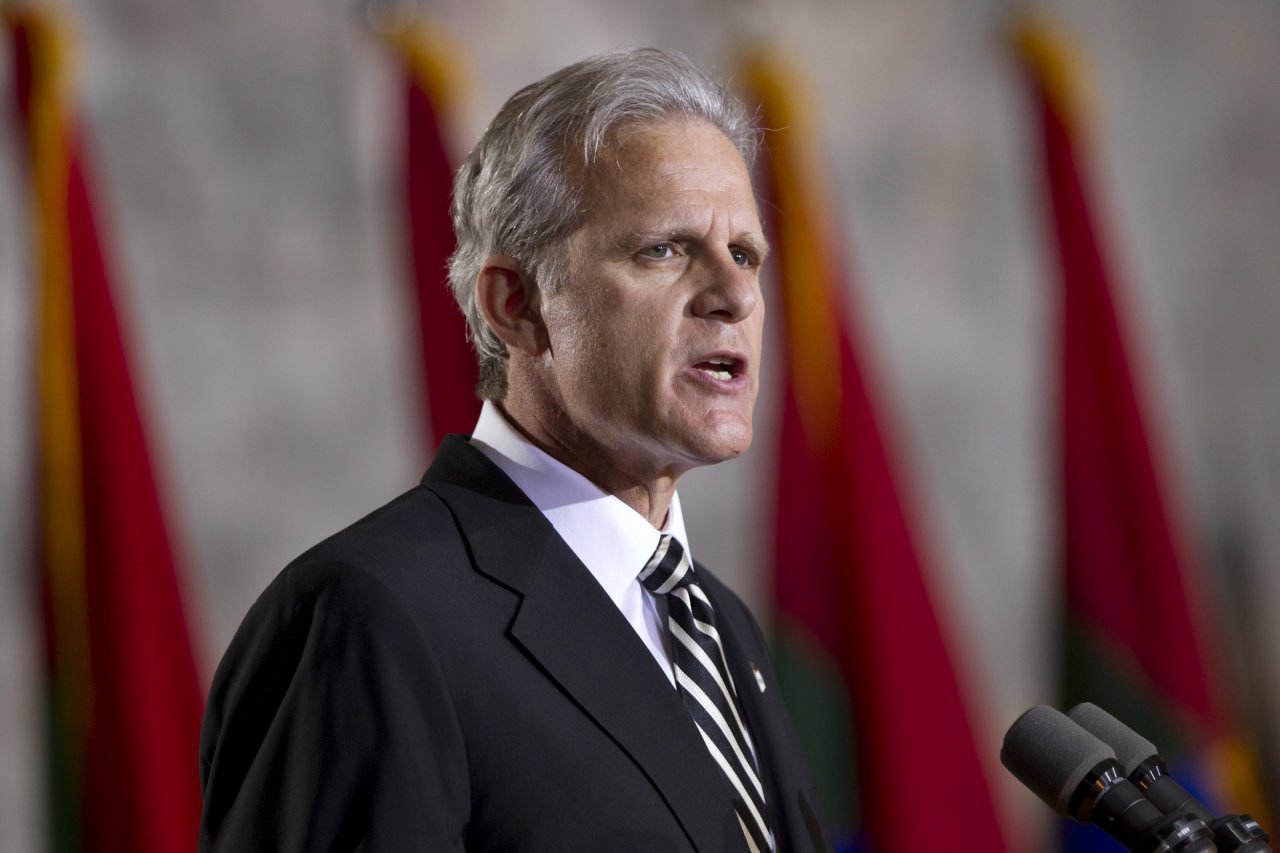

Updated | In late June, Michael Oren, a celebrated Middle East historian turned Israeli diplomat, embarked on a nationwide U.S. tour to promote his new memoir, which recounts the four years he spent in Washington as the top envoy of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. The book was scheduled to be released this fall, but Oren says he pressured Random House to publish it now because "Israel is at a fateful juncture" due to the Iran nuclear talks and a French Middle East peace initiative making its way through the United Nations Security Council. Unlike other diplomatic memoirs, which tend to be bland, Oren's Ally: My Journey Across the American-Israeli Divide is provocative, as the American-born historian blames President Barack Obama for the sorry state of U.S.-Israel relations and most of what's wrong in the Middle East.

Oren says he hopes the book will "animate and inspire my readers" in advance of these challenges "to do more than just stand there." And undoubtedly, Netanyahu's American supporters will rally behind this cri de coeur. But others who closely follow U.S.-Israel relations may find the book self-aggrandizing and disappointing. In his memoir, the American-born Oren, who renounced his U.S. citizenship and now serves as a lawmaker in Netanyahu's right-wing coalition, transforms from a measured historian into a breathless polemicist. With its factual oversights, sneering tone and amateur psychological analysis of both Obama and Netanyahu's American Jewish critics, Ally tries to explain the deep rifts that have opened between Washington and Jerusalem, and between Israeli and American Jews.

The Columbia- and Princeton-educated Oren's first book was a best-selling history of the 1967 Middle East war in 2002. His second book, an ambitious account of America's centuries-long fascination with the Middle East, also became a best-seller. In his career as a Middle East scholar, Oren has held visiting professorships at Harvard, Yale and Georgetown. He has also used his intelligence, good looks and fine sense of irony to charm American audiences, from local synagogue congregations to the ladies on The View.

But the balance and objectivity Oren displays in his scholarly writing is absent from his memoir, as well as three recent op-ed pieces that summarize the most provocative parts of his analysis. One, which ran inThe Wall Street Journal under the headline How Obama Abandoned Israel, assesses the deep divide between Obama and Netanyahu and concludes: "While neither leader monopolized mistakes, only one leader made them deliberately," referring to Obama.

Oren writes that Obama has doggedly pursued "an agenda of championing the Palestinian cause and achieving a nuclear accord with Iran," at the cost of Israel's security. He repeats familiar Israeli accusations of Palestinian perfidy and Iranian extremism to underscore what he views as Obama's naivete. At the same time, he downplays any role Israel played in its recent flare-ups with the U.S.—such as announcing settlement expansion during a 2010 visit by Vice President Joe Biden or Netanyahu's high-profile efforts to enlist Congress against Obama's Iran diplomacy—as either accidental or principled.

Oren's accusations have drawn heated denials from the Obama administration. State Department spokesman John Kirby rejected them as "false," noting that Oren was too far removed from the real diplomatic action to know what was going on. Dan Shapiro, the U.S. ambassador to Israel, protested to Netanyahu, asking him to distance himself from Oren's accusations. In yet another sign of how toxic relations are, Netanyahu refused.

Martin Indyk, who was deeply involved in U.S.-Israel contacts as Obama's special envoy to the Israel-Palestinian peace talks, says Oren was mostly out of the loop. "This goes to a lot of the things that are in his book. He relates something where he has partial knowledge," Indyk, now vice president of the Brookings Institution, told CNN's Fareed Zakaria GPS on June 28. "The relationship needs to be repaired, not further damaged. And what Michael is doing is causing it further damage for no good purpose."

Oren charges that Obama violated the two "sacrosanct" rules that have long defined the U.S.-Israel relationship: no public differences on policy that "common enemies" can exploit and no surprises by either government. As examples, he cites Obama's 2009 criticism of Jewish settlements in the West Bank as an obstacle to peace and his demand that Netanyahu freeze settlement construction. He also claims the president "altered 40 years of U.S. policy" by endorsing Israel's pre-1967 borders with land swaps as the basis for an Israeli-Palestinian peace deal.

It's true that past Israeli and American administrations have tried to keep their policy differences private. All governments prefer quiet diplomacy to public confrontations. But Obama is hardly the first U.S. president to openly disagree with Jerusalem on the issues of settlements and Israel's borders. Ever since the 1967 war, when Israel occupied the West Bank, every U.S. administration has called for Israel's withdrawal to the pre-1967 lines, with minor adjustments for security. These and other disagreements have regularly burst into public view since 1969, when President Richard Nixon's administration first unveiled a peace plan that included the idea of adjusted 1967 borders. President Ronald Reagan's 1982 peace plan included the same parameters. Both came as a surprise to Israel, which angrily rejected them. Other public disagreements include President Gerald Ford's 1975 "reassessment" of relations in response to Israel's unwillingness to make further concessions to Egypt in U.S.-brokered disengagement talks. "You don't understand, I'm trying to save you," Secretary of State Henry Kissinger told Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin at the time. "You are making me, the secretary of state of the United States of America, wander around the Middle East like a Levantine rug merchant.… Are you out of your mind?" President George W. Bush regarded the West Bank as occupied territory and the settlements as illegal. The U.S. has also consistently refused to recognize Israel's exclusive claim over Jerusalem, a position recently underscored in a Supreme Court decision.

In ignoring these disputes, Oren also omits President Jimmy Carter's public spats with Prime Minister Menachem Begin over Israeli settlement expansion; Reagan's decision to withhold arms shipments from Israel after its 1981 bombing of Iraq's Osirak nuclear reactor; Reagan's sale of surveillance aircraft to Saudi Arabia despite fierce Israeli opposition; and his decision to open talks with the Palestinian Liberation Organization, which outraged then-Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir. President George H.W. Bush clashed openly with Shamir over Israel's settlement policy, and there was considerable animosity between President Bill Clinton and Netanyahu during his first term as prime minister.

For a scholar of Oren's caliber, these omissions are disappointing. His tendency to dabble in armchair psychoanalysis is amateurish. In one of Ally's most controversial passages, Oren suggests Obama's major overtures to the Muslim world—from his 2009 Cairo speech in which he extended a hand to Iran, to his failed effort to reach an Israeli-Palestinian peace accord—were driven by a deep need to make up for how his Muslim father and stepfather abandoned him as a child. "Perhaps, too, his rejection by not one but two Muslim fathers informed his outreach to Islam," Oren writes.

With that observation, Oren both damages his credibility as a serious historian and offends some of Israel's strongest advocates. In a statement, Abraham Foxman, national director of the Anti-Defamation League, said Oren's theorizing on Obama's relationship with the Muslim world "veers into the realm of conspiracy theories."

Oren also takes aim at American Jewish journalists, blaming them for Israel's poor image in the U.S. media. He singles out New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman, as well as what he calls that paper's "malicious" editorial page, which is edited by Andrew Rosenthal. He complains about The New Yorker editor David Remnick, Time columnist Joe Klein, The New York Review of Books and Leon Wieseltier, former literary editor of The New Republic, saying their antagonism toward Netanyahu resembles classic anti-Semitism. "The presence of so many Jews in print and on-screen rarely translates into support for Israel," he writes. "The opposite is often the case, as some American Jewish journalists flag their Jewishness as a credential for criticizing Israel."

Oren then plays the armchair shrink once more. In explaining why American Jewish journalists "nitpick" at Israel—a country he calls their "nation-state," the former diplomat suggests some resent the country for complicating their identities as Jewish-Americans. Others, he sneers, "saw assailing Israel as a career enhancer—the equivalent of Jewish man bites Jewish dog—that saved several struggling pundits from obscurity."

"I could not help questioning whether American Jews really felt as secure as they claimed. Perhaps persistent fears of anti-Semitism impelled them to distance themselves from Israel and its often controversial policies," he writes, adding sarcastically: "Maybe that was why so many of them supported Obama, with his preference for soft power, his universalist White House seders, and aversion to tribes."

In her review of Oren's book, Jane Eisner, editor-in-chief of The Forward, a national Jewish newspaper, notes that fears of anti-Semitism, now at historic lows in the United States, are not what make many American Jews distance themselves from Israel. They are "far more likely to question the controversial policies Oren cites and reject Netanyahu's persistent warnings that it's 1939 all over again," she writes. "For many Jews who came of age since 1967, Israel is seen not as David but Goliath; not as victim but as occupier. That same generation's experience of American military engagements—Iraq and Afghanistan—has understandably persuaded them that the 'soft power' Oren derides is far preferable to pursue than the reckless wars championed by George W. Bush and his contemporary acolytes."

Oren was chosen as Israel's ambassador to the U.S. largely because of his roots and his understanding of American culture. But as he travels across the states promoting Ally, he will likely learn he doesn't know his former country as well as he thought.

About the writer

Jonathan Broder writes about defense and foreign policy for Newsweek from Washington. He's been covering national security issues for more than two ... Read more