Updated | Less than a mile behind the rebel front line in eastern Ukraine, the abandoned warehouses of the Donetsk chemical factory sprawl across a chunk of the city's westernmost suburb. The homes surrounding it bear the scars of the past year's artillery bombardment. Whole apartment blocks have been burned out, and low-rise buildings are roofless and riddled with shrapnel holes.

Long-suffering elderly residents potter about the devastated streets of Donetsk's Oktyabrsky district, by now oblivious to the thunder of shellfire just a few hundred yards away. They are also unaware of a second grave danger lying deep within the grounds of that nearby chemical plant.

Inside the 2-square-mile grounds of the plant, buried under 10 feet of black Ukrainian soil, lies a concrete and steel bunker, 65 feet long, 33 feet wide and 10 feet deep. Soviet scientists painstakingly designed and built its reinforced walls in 1961. They house about 12 tons of radioactive waste. Between 1961 and 1966, the USSR's research, industry and medical facilities dumped their most dangerous radioactive materials at the site, then sealed it. A year later, information on the type of substances stored there vanished. "The data on the exact kind of radioactive materials there has been lost since 1967," says Vladimir Perevoznik, technical director of Radon, the Ukrainian state enterprise responsible for the security of the site until it was captured by Russian-backed fighters in the spring of last year. "But we do know that there was cesium, cobalt, strontium 90 and yttrium 90."

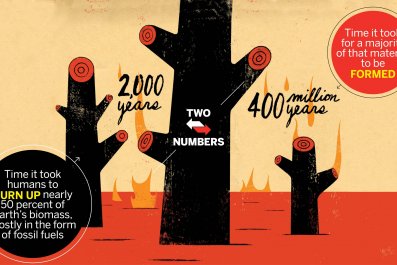

Most of the waste is probably cesium isotopes, Perevoznik explains. They have a shelf life ranging from two to 2.3 million years and are often used in medical radiation therapy, or in the construction industry to gauge moisture levels or wall thickness. But even a small amount of cesium can be lethal without protective casing. "A very small device with cesium 137, no bigger than a pen, was lost during the construction of a building in Kramatorsk [a town in Donetsk region] in the 1980s," says professor Konstantin Loganovsky, head of the radiation psychoneurology department at Ukraine's National Research Center for Radiation Medicine. "Four children died from leukemia, two adults died, and 17 people were disabled for life. The ampoule had been built into the wall, and the entire building was exposed."

A 2002 inspection by Ukraine's State Nuclear Regulation Committee found that the level of radiation in the bunker was extremely high, at 725.2 billion Becquerel. To put that in context, after a tsunami struck the Fukushima nuclear reactor in 2011, the Japanese government announced that cesium radiation of more than 200 Becquerel per kilogram in drinking water was unsafe.

Exposure to the bunker's level of gamma radiation, even for a short period, could cause acute radiation sickness. In the wrong hands, cesium 137 could cause organ failure, cancer or swift death. And there are now potentially tons of cesium 137 in rebel hands.

In theory, the bunker and protective casing should render the radioactive chemicals safe, despite their proximity to the front line of the battle between Ukrainian forces and pro-Russia rebels. It's unlikely to be breached by even the heaviest shelling. "In order to get to the material itself, one needs to break the concrete cover, iron and lead layers, so the site cannot be destroyed very easily," Perevoznik says.

In other words, the safest thing to do is leave it undisturbed in the bunker.

Yet in early July, Ukraine's State Security Service, the SBU, handed Newsweek a dossier indicating that rebel fighters had started removing the radioactive waste. Their intelligence suggests the separatist fighters have enlisted scientists from Russia to help them make a "dirty" radioactive weapon.

The dossier contains three documents that the SBU says it obtained along with hundreds of others from a hacked rebel email account. The documents, which Newsweek could not independently verify, appear to be military orders from the self-proclaimed Donetsk People's Republic. Written in Russian, they instruct officials to allow a group of nuclear specialists from the Russian Federation to access the site. Apparently signed and stamped by DPR Prime Minister Alexander Zakharchenko, one document orders the rebel Vostok battalion to provide armed protection for the Russian scientists, while instructing the DPR's Ministry for Emergency Situations to provide vehicles to carry the waste and evacuate people living within 2 miles of the site between July 2 and 18.

It is not clear from the documents whether the Russian specialists are private individuals or employees of the Russian state. According to the instructions, the removal of the waste needs to be carried out "to prevent an ecological disaster."

Russia's state nuclear agency, Rosatom, denied sending specialists to the site. "There were no official requests [for us] to deliver services to Donetsk," says Andrei Ivanov, a Rosatom spokesman. "Furthermore, the information that there is radioactive waste at the specified factory is open to question." Ivanov adds that there are a small number of private Russian companies capable of removing radioactive waste.

The dossier also contains a report from an undercover SBU agent in Donetsk and refers to intercepted radio and telephone communications. It is this agent's report, based on information apparently gathered during a vodka-soaked night with a separatist fighter and passed clandestinely to an SBU handler, that has sparked fears that the DPR is working on a dirty bomb. (The SBU said it could not provide recordings or transcripts of these conversations to Newsweek.)

According to the agent's report, a member of the rebel Somalia battalion boasted that the unit's infamous leader, Mikhail Tolstykh, better known by his nickname, Givi, told his fighters that the DPR "would soon have an atomic weapon." Tolstykh is infamous for his indiscretion. His unit uploaded a film of him beating and threatening Ukrainian prisoners of war at Donetsk airport in January. He has been sanctioned by the European Union for his role in the conflict.

Yuriy Tandit, chief adviser to SBU Director Vasily Hyrtsak, said: "The DPR plans to use radioactive material to create a dirty bomb with which it can blackmail the international community and the government of Ukraine."

The SBU says that despite the July date given on the documents, intelligence from their agent and the intercepts suggest that Russian specialists visited the site and moved some of the waste to a military base in June, leaving their protective gear with the separatist fighters.

On a visit to Donetsk in mid-July, Newsweek confronted the DPR's deputy defense minister, Eduard Basurin, with the documents. Sitting on the terrace at the Legend Café, he scowled momentarily. Then, flashing a somewhat forced smile, he threw the printouts down on the table and ordered another beer.

"Fake," he said. "Why is this fake? It refers to people and special units that do not exist. And we don't have any repository."

When pressed, Basurin acknowledged that the individuals addressed in the correspondence are DPR officials. It is only the Russian specialists who cannot be traced. Over the course of the interview, toward the end of his last lager, Basurin's story started to shift.

"Everyone knows that there is a small repository with waste," he said. "It also existed during Ukrainian times."

Asked if he knows the bunker contains cesium, he said, "Maybe. I don't know. There were so-called radioactive metals—everyone knows about that. But the story that we have a repository here and that we signed an agreement with Russia is fake."

Questioned about Zakharchenko's stamp and signature, the deputy minister was evasive. "I don't know what his signature looks like. But it is easy to fake."

NATO declined to comment on the dossier, with an official responding that the military alliance is "not in a position to offer an assessment on the specific issue raised."

U.S. and U.K. intelligence were similarly unable to confirm or dispute the evidence in the dossier, but diplomatic sources tell Newsweek that the issue was referred to the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, which raised it during the talks on July 21 in Minsk, Belarus, with Russia and the self-proclaimed republics of Donetsk and Luhansk. The OSCE, which has a mission in Donetsk to monitor the conflict, would say only that it has "noted" the dossier.

In Donetsk, Newsweek was able to verify that the Vostok battalion controls access to the radioactive waste facility. Several civilians living a little over a mile from the site said they had periodically been offered help to evacuate throughout the conflict, but had not been forced to leave the area at any particular time. "If someone wants to move, the DPR helped find new places, but it's not necessary," said Maria Stanova. "I've stayed here throughout the war, and I don't want to leave. I don't know anyone who has been forcibly moved."

Tight security at the checkpoints, bristling with heavy machine guns and manned by agitated rebel fighters, made it impossible for Newsweek to get close to the chemical plant.

If the SBU's intelligence is accurate, the development of a rebel dirty bomb would bring an alarming new dimension to a war that has grown increasingly savage as it drags into a second year. The U.N. estimates the conflict has already taken more than 6,700 lives, with the true number likely much higher. Rights groups accuse both sides of war crimes, such as torturing prisoners and killing civilians.

Although a dirty bomb has nothing like the destructive capacity of an atomic bomb, the threat of such a weapon in the hands of an ill-disciplined and ruthless fighting force is a terrifying prospect. The extent of radioactive contamination would mostly be determined by method of delivery and wind patterns, experts say. The threat is greatest if radioactive materials can be refined to dust and dispersed by a high-explosive detonation at a great height, or if radiation contaminates a water supply. Detonation at ground level is unlikely to spread radiation far, but it is the invisible nature of the poison that makes the dirty bomb such an effective terrorist weapon.

"A dirty bomb actually has a limited radiological impact," says Loganovsky. "But after an explosion, there will be chaos and panic in society. Normal life will be destroyed by fear of radiation poisoning, so it's a very significant threat."

The unpredictable nature of a dirty bomb makes it a dangerous weapon even for those deploying it. But throughout the conflict, both sides have shown scant regard for civilian lives, shelling populated areas indiscriminately. And it is the Russian-backed forces that have committed the most flagrant war crimes, rights groups say. "Two of the deadliest attacks with civilian casualties in recent fighting were due to the unlawful use of unguided rockets by the Russian-backed rebels," says Ole Solvang, senior emergencies researcher at Human Rights Watch.

In one incident, four multiple rocket launch systems fired dozens of rockets at a densely populated suburb in the port town of Mariupol, killing 31 people and injuring more than 90. Another rebel rocket attack tore apart a passenger bus at a checkpoint, killing 12 civilians and wounding another 18.

Despite a supposed cease-fire, the conflict shows no sign of resolution, and rebel discipline continues to be suspect. Driving out of Donetsk, past the city's bombed-out bridges and its scattered anti-tank defenses, Newsweek went through five fortified checkpoints, four of them defended by a handful of teenage boys and a couple of aging superiors. On the front line, at the last checkpoint before Ukrainian territory, sunburnt soldiers swayed with their Kalashnikovs, visibly drunk. A solitary prostitute lingered nearby, clad in white knee-high boots and little else.

"This war won't end until we have the whole of Donetsk and Luhansk regions," said one separatist fighter, referring to an area more than twice the size of the land the rebels currently occupy. "We'll kick the 'Ukrops' back to Kiev."

But with Russian support muted as President Vladimir Putin uses the Iran nuclear deal to negotiate a thaw in relations with the West, the rebels have limited resources to achieve that goal. Now Ukraine says a dirty bomb could be one of them.

This article has been updated to include comment from an SBU official and links to source documents.

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly referred and linked to a map, stating that it was included in a dossier provided to Newsweek by the SBU. The map was not in the dossier and has been removed from the story.