Updated | Until recently in Washington, the only issue Democrats and Republicans seemed to agree on was Israel. Though lawmakers on opposite sides of the aisle have bickered incessantly over Obamacare and federal spending, they always passed pro-Israel security bills with overwhelming majorities—from slapping new sanctions on Iran to reaffirming the Jewish state's right to defend itself.

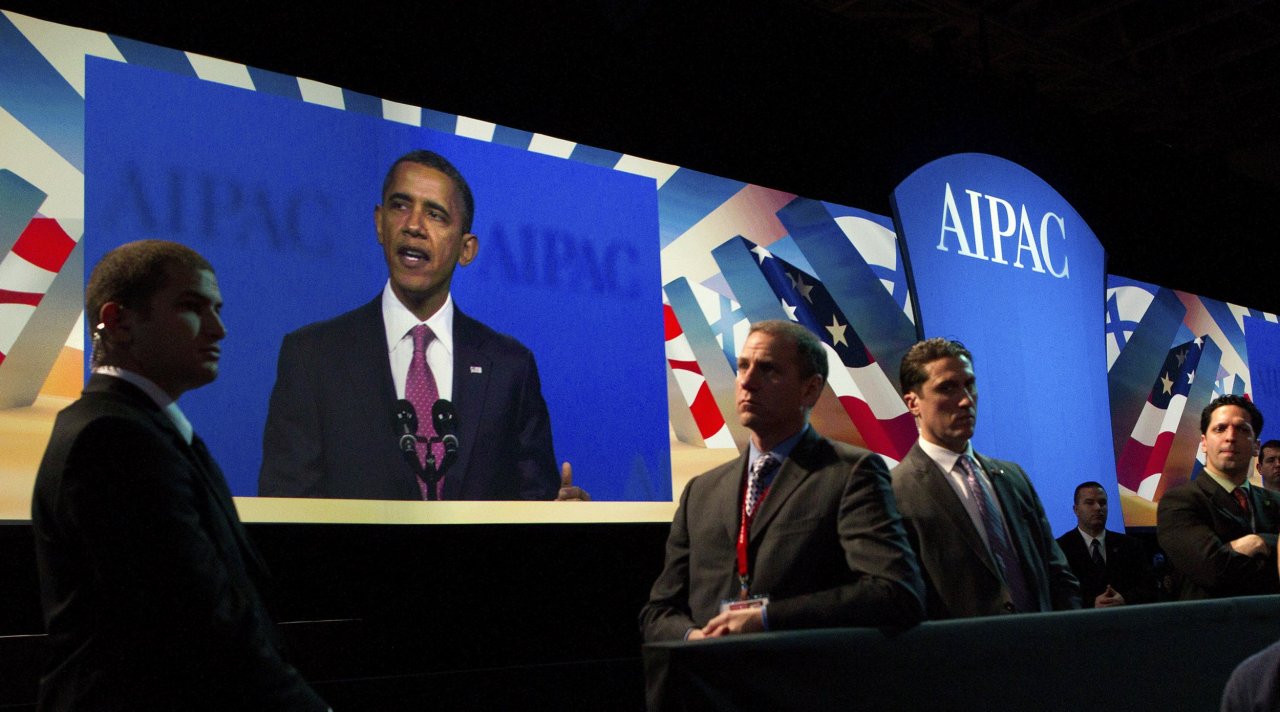

But as Congress prepares to challenge President Barack Obama's nuclear deal with Iran this month, the cause that once brought together Israel's bipartisan supporters has at least momentarily divided them. And that divide has exposed a larger rift between Jewish Democrats and Israel's main U.S. lobby, the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC).

The Iran deal constrains the country's nuclear program for 15 years in return for ending international sanctions. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, all Senate Republicans, most House Republicans and the entire field of GOP presidential candidates oppose the deal, saying it clears the path for Iran to become a nuclear power. A growing number of Democrats, however, disagree. In fact, there now appears to be enough Democratic support in the House and Senate to prevent Republicans from blocking the deal.

With ratification of the agreement now seemingly inevitable, some analysts say it could hurt AIPAC's standing on Capitol Hill. For years, the lobby was among the most formidable in Washington, respected and, because of its hardball tactics, feared. So this summer, when AIPAC met with hundreds of lawmakers and spent millions of dollars on TV ads in an attempt to block the agreement, some thought the group might thwart the president.

Yet in challenging Obama on Iran, AIPAC may have overestimated its influence. While a vote on military aid for Israel is an easy one for lawmakers, a vote on the Iran deal is far more complicated: It involves matters of war and peace, which lawmakers have historically granted presidents wide latitude to pursue. "The strength of any 800-pound gorilla lies in the perception that his power is so significant that no one challenges him," says Robert Wexler, a former Democratic congressman from Florida and a supporter of the deal. "But if the 800-pound gorilla challenges and loses, then the deterrence factor is seriously weakened." (AIPAC did not respond to a Newsweek request for comment.)

Part of the lobby's clout has been its long-standing claim that it speaks for American Jews on Israel-related issues. But during the recent scramble for support on Iran, J Street, a rival pro-Israel lobby that supports the nuclear deal, has become an influential player and liberal alternative, despite a budget that's a fraction of AIPAC's. "The illusion that there's some form of wall-to-wall unity and unanimity on these issues in the Jewish political community has probably been put to rest by this fight," says J Street President Jeremy Ben-Ami.

The battle with Obama wouldn't be the first time AIPAC has been defeated by an American president. In 1978, the lobby failed to get Congress to stop Jimmy Carter's sale of advanced warplanes to Egypt and Saudi Arabia. In 1981, AIPAC lost its bid to block Ronald Reagan's sale of surveillance aircraft to the Saudis. And in 1991, the group fell short in its effort to win loan guarantees for Israel because of George H.W. Bush's concerns that the money would be used in West Bank settlements.

But in each of those squabbles, AIPAC came close to winning, which burnished its image. And in subsequent elections, the lobby mobilized pro-Israel donors to help oust political opponents, most notably Republican Charles Percy of Illinois, chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, in 1984. "All the Jews in America, from coast to coast, gathered to oust Percy," boasted Tom Dine, AIPAC's executive director at the time. "And the American politicians—those who hold public positions now, and those who aspire—got the message."

Today, no one is suggesting that AIPAC will have any trouble winning congressional support for U.S. military aid to Israel. Analysts agree that the security relationship between Washington and Jerusalem is strong and will remain so. Stephen Walt, a Harvard professor who co-authored a book critical of the Israel lobby, suggests that AIPAC's lobbying against the Iran deal may wind up improving Jerusalem's leverage when it's time to negotiate an enhanced security package that Obama offered the Jewish state as a way to make the accord more palatable. Though Netanyahu is holding off on those discussions until after Congress votes on the nuclear accord, Israel's security establishment has quietly signaled to Washington that it would like to increase the $3 billion in U.S. military aid Israel has received annually since 1979 and extend the arrangement for several decades.

But the lobby may have more trouble convincing the Obama administration to provide the kind of political support Jerusalem has grown used to. After Netanyahu took a position against Palestinian statehood during his March re-election campaign, Obama told him that Washington would "reassess" its options on U.S.-Israel relations and Middle East diplomacy. Since then, there has been speculation that the United States won't block some pro-Palestinian resolutions at the United Nations Security Council.

The administration can probably count on J Street to provide political cover. The left-wing, pro-peace lobby draws its support from younger, more secular Jews who have grown disillusioned with AIPAC's support for Netanyahu's harsh policies toward the Palestinians. And since Obama took office in 2009, some say, AIPAC's stance on Israel has been indistinguishable from that of Netanyahu and the Republican Party. "In the 1980s and 1990s, it was very easy to be bipartisan," says Ben-Ami. "There were no arguments. But today, there's a real argument, and you have to choose which side you're on. That's uncomfortable for individuals and organizations. It raises issues of dual loyalty."

Until recently, AIPAC has managed to keep lawmakers in line by using vote studies on Israel-related bills to influence which candidates receive hefty campaign contributions. But the tally of 29 Democrats in the Senate and 74 in the House who support the Iran accord suggests a growing number of lawmakers are ready to defy the lobby, thanks in large part to effective fundraising by J Street. AIPAC still has the power to influence which candidates receive pro-Israel PAC money, "but I don't think the perception of that influence will be nearly as great," says Wexler, who heads the S. Daniel Abraham Center for Middle East Peace. Says Douglas Bloomfield, a former legislative director for AIPAC and now a critic of the lobby, "There will be a greater inclination to resist."

With the 2016 congressional campaigns getting underway, some analysts say it's critical for AIPAC to punish supporters of the Iran deal. Political observers will be watching the Wisconsin Senate race between Tea Party Republican Ron Johnson, an outspoken opponent of the agreement, and former Senator Russ Feingold, a Jewish Democrat who supports the accord. Another telling contest will be the Illinois Senate race between Republican Mark Kirk and Democrat Tammy Duckworth, an Army helicopter pilot who lost both her legs during the Iraq War and is undecided on the deal. Even Jerrold Nadler, an 11-term Democrat from New York, who is Jewish, could face a primary challenge since he has publicly backed the nuclear agreement.

And those who think the Iran issue will fade away once the deal gets through Congress had better think again. An Obama victory there is likely to galvanize Republicans—particularly as the 2016 election looms. Both Kirk and Republican Lindsey Graham of South Carolina, a long-shot presidential contender, are crafting a new set of non-nuclear sanctions that would deprive Iran of nearly all the economic benefits it's getting from the deal. Some of Obama's supporters predict Republicans will make the Iran deal the Obamacare of foreign policy and never stop trying to kill it.

"The fight is not over just because the Iran deal gets past Congress," says Dylan Williams, J Street's vice president of government affairs. "It's something we're all going to have to keep our eye on for years."

That's something on which all sides seem to agree.

Correction: This article originally incorrectly described Republican Senate candidate Mark Kirk as a former AIPAC employee. He has never worked for the organization.