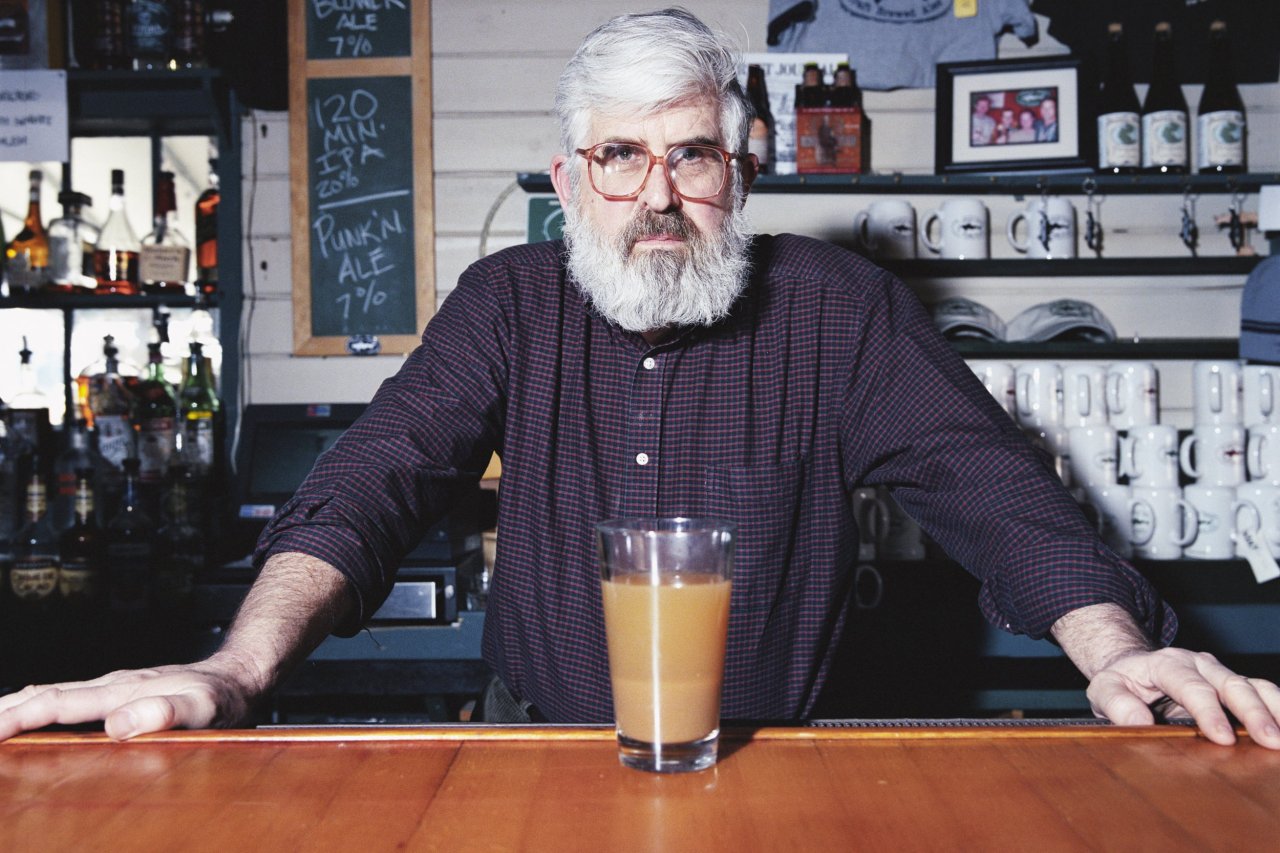

While today beer is mostly thought of as a fun and savory drink that makes us social, talkative and happy, it might also be much more than that. It could be a key to unlocking the secrets of ancient medicinal remedies that humans created over millennia to fight diseases that plagued them from the beginning of time.

It's not a moon shot. It's not even that far-fetched. In the days before pills and ointments filled our medicine chests, the sick were treated with brews and herbal cocktails—often of the alcoholic variety. In fact, before the advent of modern medicine, alcohol was the universal drug, Patrick McGovern of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology wrote in a 2010 study looking at the anti-cancer potential of fermented beverages.

The core health benefits of alcohol are obvious, he points out: It relieves pain, stops infection and kills bacteria and parasites in contaminated water. It also has nutritional advantages. During fermentation, yeast and bacteria break some of the ingredients into easily digestible nutrients that the body can absorb quickly, says Brian Hayden, an anthropologist at Simon Fraser University in Canada.

But over the years, beer also was used as a medium by which many other medicines were delivered. Cultures all over the world crafted their own versions of beer. Egyptians used barley, Incas brewed a corn beer they called chicha, and Chinese made rice "wine" (which should probably be called "rice beer" because rice is a grain and wine is technically a drink of fermented fruit). As brewers perfected the process, they realized that alcohol had another advantage: It could dissolve many compounds that water couldn't. They began to experiment with potentially beneficial additives in their concoctions, from leaves and roots to berries, nectar, honey and even tree sap and resins.

Ancient texts list plenty of therapeutic cocktails. McGovern wrote that of the thousand prescriptions found in ancient Egyptian medical papyri, a large number included wine and beer "as dispensing agents," with "numerous herbs (bryony, coriander, cumin, mandrake, dill, aloe, wormwood, etc.)" added. Mixed, soaked and steeped in beers and wines, the plants were administered for specific maladies. Traditional Chinese medicine also features an extensive list of medicinal plants delivered via fermented beverages. For example, wormwood and mugwort, plants belonging to the Artemisia genus, were often added to rice brews.

"Whenever we looked in different parts of the world, fermented beverages are the ones used to administer various medicinal agents," McGovern says. In addition to its dissolving properties, alcohol made these mixtures more palatable, just like "a spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down," says Max Nelson, a professor at the University of Windsor.

In his book The Barbarian's Beverage: A History of Beer in Ancient Europe, Nelson discusses several ancient brews found in medical texts. Antyllus, a Greek surgeon who lived in Rome in the second century, wrote about mixing brews with unripe sesame plant fruit or crushed earthworms and palm dates for "good and plentiful breast milk in women." Later, Greek physician Philumenus recommended "beer with crushed garlic as an emetic for poisonous asp bites." Marcellus Empiricus, a Latin medical writer from Gaul, suggested using beer "to soak an herbal suppository to expel intestinal worms," and also noted that beer works well "against coughs when drunk warm with salt." Greek physician and medical writer Aëtius of Amida suggested applying beer with mustard on arrow wounds.

Later on, medieval European medics came up with their own therapeutic libations: Hot ale was recommended for chest pains, "old ale" for lung disease and "new ale" for sleep problems. Welsh ale, mixed with various herbs and other fixings, was advised for several ailments. One recipe suggested rubbing "plain ale" into the scalp to get rid of lice. The Nordic cultures made grog, a complex hybrid beverage in which cereals and other ingredients were brewed together—wheat, rye or barley fermented with cranberries, lingonberries and honey. The concoction was then spiced up with herbs—bog myrtle, yarrow, juniper and birch tree resin—that likely had medicinal qualities, McGovern says.

Whether any of these things actually worked is still up for debate. Many of history's remedies have been lost due to "cultural collapse and destruction by natural and man-made calamities," says McGovern. But modern research into primordial medical remedies has been incredibly fruitful. For example, Egyptian and Greek texts mention willow tree bark, from which acetylsalicylic—more commonly known as aspirin—was eventually derived. Locals of what is now Peru used the bark of some South American trees to treat malarial fever. Later, the bark's medicinal compound was isolated into quinine, which remained a staple for malaria care for over a century.

Similarly, Native Americans steeped Canadian yew needles into a tea used as an arthritis treatment; researchers later discovered a compound in the tree's bark that eventually led to the cancer-fighting drug Taxol. In addition, in the past decade several plant-based drugs have been introduced into modern medicine. To name just a few: Capsaicin, from Capsicum annuum (a variety of pepper), is now used as a pain reliever, and galantamine, from Galanthus nivalis (the pretty snowdrop flower that blooms in many spring gardens), is being used to treat Alzheimer's disease.

Of course, not all early pharmaceuticals possessed the curative effects they were believed to have. "Superstitions, misguided religious injunctions, or unfounded psychological notions might creep into a tradition over time," McGovern wrote—such as "submerging a rhinoceros horn or bull's penis in a modern Chinese wine to convey its strength or other sympathetic attribute." But there's been enough gold flakes in the stream of historical remedies that McGovern, working with Caryn Lerman, deputy director of the University of Pennsylvania's Abramson Cancer Center, decided to launch a project they dubbed Archeological Oncology: Digging for Drug Discovery. The goal is to investigate whether the remnants of antediluvian leftovers of beer and other bevvies gathered from the clay and metal jars buried in tombs next to kings, pharaohs and emperors possessed any anti-cancerous properties.

As part of that project, McGovern investigated the medicinal properties of drops of liquid found in a bronze Chinese pot from the Shang dynasty, circa 1050 B.C., and a yellowish residue scraped off a clay jar from the tomb of Egyptian king Scorpion I, circa 3150 B.C. After zeroing in on a few promising compounds, cell line researchers tested their anti-cancer efficacy by adding them to various malignant cells in test tubes. The results were encouraging. Several ingredients showed anti-cancerous activity against certain types of lung and colon cancer. For example, isoscopolein (from the sage and thyme added to Egyptian beers) stimulated a protein that protects against DNA mutations and acts as a tumor suppressor. Artemisinin (from wormwood and mugwort in Chinese rice wine) and its synthetic derivative, artesunate, were very promising in inhibiting the growth of lung cancer cells.

Ancient beers may hold keys to promising therapeutics, but modern brews are also filled to the brim with potential. Chemists at the University of Washington, for example, are investigating humulones, which are substances derived from hops, in hopes that they may lead to new meds for treating diabetes and some forms of cancer. Other studies found that in addition to its pharmaceutical promises, beer offers a slew of preventive medicinal benefits. It lowers the risk of cardiovascular disease and kidney stones and even improves cognitive performance in the elderly, says Charles Bamforth, a professor of malting and brewing sciences at the University of California, Davis. Beer also contains vitamin B, an antioxidant compound named ferulic acid and a lot of grain-derived fiber, which Bamforth posits in his study may work as a prebiotic—a food source for the beneficial bacterial colonies that live in the human gut.

Some studies suggest that beer may help fend off osteoporosis because it's high in silica, a mineral important for maintaining bone density and promoting connective tissue formation. Naturally present in the grain, silica is released during the brewing process, says Jonathan Powell at MRC Human Nutrition Research in Cambridge, England, and unlike pill supplements it is fully absorbed by the body because of its liquid form. When you look at its overall nutritional value, beer is superior to wine, says Bamforth, who is also quick to dispel the "beer gut" myth. It's not the "empty calories" that give beer drinkers their round bellies but rather their overall lifestyle and the type of food typically served with the ales and stouts—like burgers, for example. "To pin that blame on beer alone is simply unfair," Bamforth says.

So as you raise your frothy mugs this Oktoberfest, take notice—your pints will be brimming with minerals, nutrients, vitamins, antioxidants and loads of fiber. You just need to consume this healthy fusion in moderation, beer scientists caution. "Drinking beer shouldn't be an end in itself," Bamforth says. "It should be a pleasurable, sensual experience."