The three-story redbrick building at 435 South Fifth Street in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, is on the ragged edge of what New York magazine in 1992 called "the new bohemia," a waterfront warehouse district primed to receive the artists priced out of Manhattan. The conceptual artist Mark Lombardi arrived in the city's newest, coolest art district about five years after that memorable designation, eventually settling in the neighborhood's Dominican section. He was coming from decidedly un-bohemian Houston, where he had worked for the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, started galleries and tried to publish books of investigative journalism before turning to conceptual art, where he had found late, improbable success. He was approaching 50, making him more than twice the age of many of the painters, gallerists and performance artists starting to crowd into the Polish taverns on Bedford Avenue, dreaming of fawning spreads in Artforum.

A visitor to Lombardi's studio would not have seen the usual evidence of the fine arts, because Lombardi was not an artist in the manner of Michelangelo or Georgia O'Keeffe. He was less interested in the creation than the idea behind that creation, echoing the cerebral ethos of conceptualism. The movement had been defined in 1967 by the painter Sol LeWitt, who declared, "The idea itself, even if it is not made visual, is as much of a work of art as any finished product."

The concept that fed Lombardi's conceptualism was that a clandestine economy, bound by no law, shuttled money between concerns in Texas, the Middle East, the Vatican and the Beltway. That money translated into oil barrels, or bundles of cocaine, or crates of arms, and inevitably manifested itself as ruthless power of the few over the many. Lombardi thought the best way to defeat this corrupt global cabal was to show it its own reflection. As journalist Patricia Goldstone writes in Interlock: Art, Conspiracy, and the Shadow Worlds of Mark Lombardi, the first major book about the artist, his work was "a continual visual history of the world's shadow banking system" and "the evolution of a shadow, worldwide web of private intelligence and military firms." No haystacks or wheat fields for this artist; no rainy Paris boulevards.

Lombardi's "narrative structures," as he called them, were based on information he culled from public documents, and while there is a sort of mad beauty to the crisscrossing arrows of his drawings, their main currency is not beauty but information, the feverish connections between the Saudis and the Bushes, between the millions shuttled from London to Riyadh and a brutally suppressed peasant uprising Latin America. He was like an investigative reporter whose medium just happened to be the schematic drawing.

After many years of disappointment and obscurity, Lombardi caught the public's eye in the late 1990s, with shows in Houston and then New York. The New York Times praised his "beautiful" drawings for their ability to "suggest an evil order underlying apparent chaos," comparing him in that regard to postmodern novelist Thomas Pynchon. In 2000, he took part in a group exhibition at PS1, in Queens; meanwhile, the Whitney Museum of American Art was planning to buy one of his major drawings. He was becoming, as Joe Biden might say, "a big fucking deal."

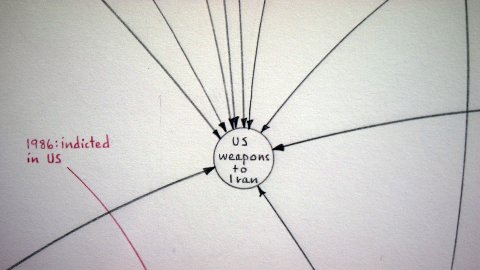

For reasons Goldstone does not sufficiently elucidate, Lombardi became unhinged as spring approached. Yes, he was divorced and in debt, but these were chronic concerns, which artistic fame could easily alleviate. An accident with an errant sprinkler pipe damaged a drawing called BCCI - ICIC & FAB (a version of which the Whitney would eventually acquire). The apogee of his artistic and investigative efforts, the drawing focused on the operations of the Bank of Credit and Commerce International, a rogue institution straight out of a John le Carré novel. Reconstructing BCCI over the course of four sleepless days may have, Goldstone speculates, "unhinged the artist" for good. But this is only conjecture.

Whatever the case, friends remember Lombardi as "really on edge," haunted and paranoid in the final weeks of his life. On March 22, he was expected at the opening of the Whitney Biennial in Manhattan but never showed. Friends became worried and called the police. An officer from the 90th Precinct, which is across the street from Lombardi's studio, found him in his apartment, hanging from a sprinkler pipe. Next to him was a bottle of champagne.

That he was not much of a champagne drinker is only one of several inconsistencies about Lombardi's death. The bigger one is that while he may indeed have suffered from a psychiatric disorder, he was on the cusp of great professional success and thus unlikely to seek a permanent way out. That's why some have never been convinced that Lombardi committed suicide. "You're never going to come up with a good reason for him killing himself," the gallerist Deven Golden, who showed Lombardi's work, told Goldstone.

Goldstone is clearly attracted to this line of thinking, despite no evidence of Lombardi having been killed by one of the many powerful and/or dangerous men who figured in his work. True, it would make for a better story, but the story is pretty compelling as is. For example, Goldstone notes that "the FBI was fully aware of Lombardi's art" and that its agents came to the Whitney after 9/11, demanding to see his BCCI drawing. "Nameless security officials," Goldstone writes, also closed down a posthumous show of Lombardi's works at the Drawing Center, a well-regarded lower Manhattan institution, on opening night.

The Wall Street Journal, which is not generally known for trafficking in lefty conspiracy theory, noted in 2002 that Lombardi's drawings "suddenly have a role in the global war on terrorism," singling out their "impressive" scope, from the Saudi banker and Osama bin Laden associate Khalid bin Mahfouz to Arkansas tycoon and Clinton friend Jackson T. Stephens. His drawings, the Journal said, featured "some of the shadiest and most familiar individuals in finance and politics worldwide." It is entirely possible that Lombardi went one provocation too far.

However he died, Lombardi had achieved the dream not only of artists but of conspiracy theorists: He had gained attention from the powers that be.

Mark Lombardi was born in 1951, in Syracuse, New York. He was 12 when John F. Kennedy was assassinated, and, as Goldstone tells it, the bloodshed of Dealey Plaza in Dallas would forever haunt him, giving his worldview an ominous cast.

Lombardi went to Syracuse University in 1971 to study art, only to discover, as Goldstone writes, that he "lacked the ability to draw." That might end most artistic aspirations, but it did not end Lombardi's. He was a devoted disciple of James Harithas, then a professor at Syracuse and head of the Everson Museum of Art, an unabashed left-wing provocateur. A show organized by the Everson, "From Teapot Dome to Watergate," had a profound effect on Lombardi, aligning him with the explicitly political, often didactic sensibility that was to mark his work.

After college, Lombardi followed Harithas, who had been hired by the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston and was in the midst of creating there what Goldstone calls an "anarchic spirit" at odds with the conservative image of Texas. She paints an unflattering picture of the erstwhile Lone Star Republic as a "parallel state" drunk on oil money and uninterested in political scruples. Clearly sympathetic to the conspiratorial mindset, Goldstone aligns what she calls the Texas Raj with the German-Jewish bankers of Manhattan and the military-industrial complex tumescing in the Beltway. Goldstone can, sometimes, seem to tease out the kinds of connection between power and capital that animated Lombardi's art, as well as the novels of Pynchon and Don DeLillo. She can also, however, seem only a step away from the graying hippie passing out leaflets about the New World Order and the gold standard.

By the late 1980s, after about a decade in the "boys' club of badly behaved boys" of Houston, as Goldstone calls it, Lombardi abandoned any hopes of becoming a painter. He started two art galleries, but he was as inept an entrepreneur as he had been a draftsman. Without many prospects, he drifted toward the deadly seas of middle age.

His breakthrough came in 1987, as he was talking on the phone with Leonard L. Gumport, a lawyer in Los Angeles. (Lombardi would later put the conversation in 1993, but Gumport stands by the earlier date.) Lombardi wanted to know about the arms dealer Adnan Khashoggi, whose financial entanglements Gumport was trying to unravel. As they delved into the complex matter, Gumport suggested that Lombardi draw an explicatory interlock, "a type of flowchart used in antitrust litigation and accounting that involves graphing the relations between interlocking boards of directors," in Goldstone's words.

Lombardi tried to publish a book on Khashoggi but failed. Yet he somehow grasped that the drawings that formed the backbone of his research were, themselves, a form of art. So he kept drawing, subsisting, as Goldstone puts it, on "alcohol and overextended credit" while allowing his marriage to dissolve. In 1996, Paul Schimmel, a former classmate from Syracuse who now headed the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art, came to Houston to judge an arts competition. He was especially astounded by a drawing called Neil Bush, Silverado, MDC, Walters & Good, which was submitted anonymously. "When I saw this obsessive-compulsive chart, filled with facts and paranoid fantasy—there was nothing like it," Schimmel said. He chose the drawing as the winner.

Mark Lombardi had what Goldstone calls "his first big recognition." He was approaching 50.

Conceptual art is not beautiful. It is like a culinary movement that declares a war against flavor, yet nevertheless demands that you taste its creations. One famous conceptualist work by Hans Haacke, Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, A Real Time Social System as of May 1, 1971, essentially traces the New York properties of a single slumlord through charts, maps and photographs. The work isn't pretty, nor wants to be, but it does convey a message as earnest and profound as that of any fresco in Venice.

Lombardi's first exhibition, in the fall of 1996, had 26 works, with titles like Charles Keating, ACC, and Lincoln Savings and Banca Nazionale del Lavoro, Reagan, Bush, Thatcher, and the Arming of Iraq. Though he collected information on thousands of note cards, the drawings were presented without explicatory legends or commentary, even if the artist's political leanings were obvious. You were supposed to be awed by the information, the astounding connections that all could see but few could trace.

That winter, when the Drawing Center in New York asked him to partake in a group show, Lombardi decided that he'd move to New York. He had, as he said, "one continual drawing in my head," and his existence in Brooklyn was devoted to translating that image into works of art. In his free time, he indulged in the chasing of women and the consumption of intoxicants. He made a business card that proclaimed "Death-Defying Acts of Art and Conspiracy." (That became the title of a posthumous German documentary about his work shown at the Brooklyn Film Festival.)

Goldstone argues that he was "the first artist to do metadata," the kind of visualization that, today, is a commonplace means of understanding the world: masses of numbers made into attractive, coherent pictures by data ninjas with Stanford degrees. Lombardi did it all without the Internet, which he apparently disdained. He stored his information on note cards, of which there were some 14,000 at the time of his death.

Today, there are 20 of his drawings in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, according to the Manhattan museum's online archive of his work. Goldstone says that the prominent Gagosian Gallery recently had one of his drawings on sale for $450,000. Harithas, his mentor, calls Lombardi "the first great artist of the 21st century," an astounding claim about someone who found his medium only in the last years of his life.

"Lombardi is more than a conceptualist or political artist," argued Jerry Saltz of The Village Voice after Lombardi's death. "He's a sorcerer whose drawings are crypto-mystical talismans or visual exorcisms meant to immobilize enemies, tap secret knowledge, summon power and expose demons." But demons dislike exposure. One way or another, they will take their toll.

About the writer

Alexander Nazaryan is a senior writer at Newsweek covering national affairs.