On a cold night late last March, retail strategist Melissa Gonzalez settled into her seat at a candlelit banquet table in the Meatball Shop's underground bar space in New York's Chelsea neighborhood. An exposed-brick wall aglow with Edison bulbs and a rustic reclaimed-wood floor made the room feel warm and welcoming. The dinner party was an intimate invitation-only event hosted by investment firm LDV Capital to connect entrepreneurs, creative executives and investors. There was one rule to the seating arrangements—it had to be boy-girl-boy-girl—and Gonzalez found herself flanked by two men: One, Matt Ruby, was a comedian and the co-producer of NYC's Hot Soup Comedy show. The other was author and notorious jerk Tucker Max.

For the uninitiated, Tucker Max obtained modest fame in the early 2000s by detailing his relentless pursuit of sexual conquests and shameless debauchery, devoid of even a shred of morality or decency, on his blog, TuckerMax.com. By dominating a subgenre that The New York Times dubbed "fratire"—politically incorrect nonfiction written for young men that skews dangerously close to misogyny—Max accumulated a large enough following that when his first book, I Hope They Serve Beer in Hell, was published in 2006, it immediately found a spot on The New York Times's best-seller list, eventually hitting No. 1 and spawning an ill-received B movie. (You may have had the misfortune of watching Max, portrayed by Gilmore Girls's Matt Czuchry, violently shitting his pants in a hotel lobby before stripping naked and slopping through a trail of his feces on the way back to his room.)

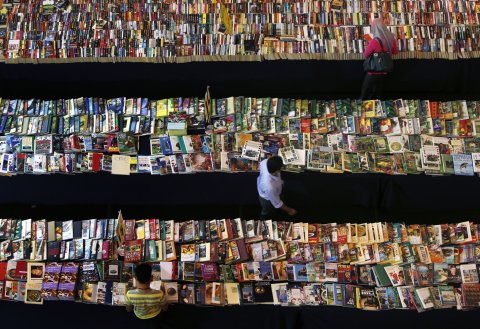

Assholes Finish First, Max's sophomore effort, made its debut at No. 3 and spent 14 consecutive weeks on the best-seller list after its October 2010 release. By the time he was ready to publish his third book in 2011, Max boldly declared he was no longer an author ("Call me a publisher") and cut a distribution deal with Simon & Schuster in order to avoid sharing so much of the profit from Hilarity Ensues—keeping, he says, "89 percent of net receipts as opposed to 15 percent of [just] hardcover sales," "tripling" his royalties and turning down two offers of a seven-figure advance in the process. After Hilarity's 2012 release, Max became the third author in history to have three books on The New York Times's nonfiction best-seller list simultaneously, after nonfiction heroes Malcolm Gladwell and Michael Lewis.

Five years later, 40-year-old Tucker Max would like people to believe that he is all grown up. He has a wife and a kid, and he is involved in at least four young media companies, including the mildly successful Tropaion Publishing, which was acquired by Lioncrest in 2012. Designated "the Jay Z of publishing" by serial entrepreneur Andrew Warner of Mixergy.com, Max is now attempting what he calls "democratizing" the industry with his new book-creation company, Book in a Box. No agent? No publisher? No time to sit down and actually write? No problem. Max and his team promise that after just a few conversations, they can deliver a professionally published book for sale on Amazon and elsewhere—all you need to do is give them $15,000 and 12 hours of your time. There's no advance, but all rights and royalties will be yours. Package options include just a finished manuscript (you're free to take it to another publisher), e-books, hardcovers and softcovers, audiobooks—even marketing support.

"When I call us a full-service publishing company, I mean it," Max tells Newsweek. The difference, he says, is that unlike traditional publishers, he's not in the business of picking winners. "Publishers are venture capitalists for book ideas. They make money when they pick books that sell a lot of copies. We make money when we do a good job turning ideas into books," he says. "Think of a gold rush. There are two business models in a gold rush. Old-school publishers are betting on gold miners; we're selling picks and shovels."

Max argues that getting a book into print has always been a rigged game. "The publishing industry has done a very good job of finding and producing books that are designed for white, upper-class intellectuals, because that's who they are as people," he says. "I think they do a very poor job of producing books for anyone outside of that demographic."

Still, with its $15,000 price tag, Book in a Box clearly isn't for everyone outside that demographic. The service mainly targets authors interested in producing nonfiction—from memoirs to business how-tos—who have money but not the time it takes to write a book. For those who can't afford the asking price, Max has yet another option. In late August, The Book in a Box Method: The New Way to Quickly and Easily Write Your Book (Even If You're Not a Writer) became available online for free download, while the paperback version costs about $10. "Our end goal is to turn this method into software," says Max, adding that a prototype is expected by next year, and the cost could be as low as $150. Then it'll be the "ultimate democratizing instrument...the way Pro Tools is for music."

The Book in a Box idea was born from a conversation Max had at that (albeit largely upper crust–dominated) LDV dinner, where he sat next to Gonzalez—the Penn State University–educated Latina CEO of pop-up retail firm The Lion'esque Group, who was peppering him with questions about getting published. "I'd been told I needed to write a book if I wanted to be recognized as an expert in my field," Gonzalez tells Newsweek. "But I'm not a writer. I didn't know how to get an agent or a publisher. I figured it was going to take years." Wasn't there a person or service she could collaborate with to quickly and easily transform her retail expertise into hardbound prose?

Max recalls looking at her disdainfully: "Are you asking me how to write a book without writing it?"

"Yes!" cried Gonzalez.

By Max's account, he was midway through a spiteful diatribe about "writing being hard work," when Gonzalez coolly interrupted him.

"Tucker, are you an entrepreneur? Because I am. And I spend all day helping people solve their problems. Are you gonna help me solve my problem or just lecture me?"

Anyone who's read Tucker Max knows his ego's not easily tamed. He left the conversation obsessed. "I dropped everything I was doing," he says. He found himself thinking about Socrates, Marco Polo and Malcolm X—authors whose locutions were put to paper with the aid of faithful scribes. He called Gonzalez and told her he'd reconsidered. He knew enough about book creation from running his publishing company; he just needed to get her talking in an informative way. His next call was to author and future Book in a Box co-founder Zach Obront, and the two of them began creating a roadmap for getting a book out of Gonzalez's head and onto the page.

Max says the process has evolved organically. "We ask every client, 'What audience do you need to reach to hit your goal?' In Melissa's case, it was people who care about pop-up retail. So we asked her, 'What do you know that's valuable to your audience?' By asking the right questions, we're able to come up with a five- to 10-page outline."

Then, through a series of interviews, a team of journalists and editors drag the book's content out of the author-talker. "It's their words, in their voice," says Max. "This is not ghost writing. We just act as a conduit between their ideas and finished books."

Gonzalez's book, The Pop-Up Paradigm: How Brands Build Human Connections in a Digital Age, was published last December, nine months after she met Max at the Meatball Shop. She says her business has doubled since the book came out. Meanwhile, Book in a Box has been garnering an impressive staff roster of industry pros, including a former HarperCollins executive editor, Mark Chait. And sales have been good—both for Book in a Box and the titles it's churning out. Most notably, Josh Turner's LinkedIn playbook, Connect, became a Wall Street Journal best-seller a week after publication, while Max reports $1.4 million in sales since January and 100 percent quarter-over-quarter growth.

But Max is not exactly treading new territory. Andrew Rhomberg, founder of reading analytics startup Jellybooks, says Book in a Box is just an expensive take on traditional author services. "It's a nice twist on a well-known proposition," he says. "But it's no revolution."

So will publishing's best-selling player remake the industry? Considering that this is the man who turned shitting on himself in a hotel lobby into a multimillion-dollar personal brand, it might be foolish to bet against Tucker Max.