"Wikipedia is amazing," exclaims Joanna Newsom.

The harpist and songwriter likely won't read the entry about herself, but she frequently dives down Wikipedia rabbit holes. "Reading something on Wikipedia will often send me off in a new direction," she says. While living in New York's Greenwich Village several years ago, for instance, Newsom found herself digging up historical nuggets on the neighborhood around Washington Square Park.

Unlike most of us, Newsom channels these procrastinatory-seeming Internet binges into song. Vivid, stunning songs of melancholy and longing, written for the harp or piano, with dizzying and self-referential verses rich with literary allusion. The song spurred by the Washington Square Park rabbit hole, "Sapokanikan" (a word I am very much afraid of mispronouncing in Newsom's presence), is named after a Native American village located in what is now lower Manhattan. Built around a winding piano melody, the song tells of forgotten mayors and Tammany Hall, of the 19th-century sonnet "Ozymandias" and of history's inevitable fade into obscurity.

When Newsom released "Sapokanikan" unexpectedly one morning in August, accompanied by a music video and the news that she would be releasing her first album in five and a half years, the Internet erupted, as if the folksinger had just climbed out of an unmarked grave. Within hours, fans—and NPR—set to work deciphering the song's tangle of references. Newsom's fan base is deep, devoted and (on a somewhat smaller scale) as obsessive as Radiohead's or Bob Dylan's a generation prior. There is even a collection of both personal and scholarly interpretations of her music titled Visions of Joanna Newsom and a modestly successful band named after her in Wales (Joanna Gruesome).

It's a strange time to be Joanna Newsom. An indie icon, one of the most revered songwriters to emerge this side of the millennium, she's spent five years in varying degrees of seclusion, dabbling in film and endlessly postponing fans' wishes for a new record. Divers, the album she's finally finished, arrives October 23 to rapt anticipation. It's lighter in tone and shorter than the 2010 epic Have One on Me, and it's the most instrumentally varied work she's ever produced, with both keyboards and synths accompanying her long-favored harp. At 11 tracks in 52 minutes, Divers is the first Newsom album since her debut not to push the extremes of the album format (there are no nine-minute baroque epics or multiple discs) and the first music she's put out since marrying actor and comedian Andy Samberg in 2013. A few numbers even sound...joyful?

For Newsom's followers, it's a monumental occasion. "I've had a Google Alert set up for this for 4 freaking years," one fan tweeted when "Sapokanikan" was released, while another said he felt "broken from an excess of happiness." Soon after the song appeared, Newsom's father, a retired doctor in California, emailed his daughter a link to the lyric annotation site Genius.com, which had posted a full annotation of it.

Did they get it right?

"In terms of all the references, they got a lot of them," Newsom says. "They didn't get them all, though!" she adds, cackling a bit mischievously.

It's a rainy afternoon in September, and Newsom and I are chatting in the empty restaurant of the Four Seasons Hotel in Manhattan. The artist's speaking voice is not much like her singing voice, though it has the same hint of untraceable twang.

Here is the part of the article where you'll either appreciate some background on Newsom or be outraged by the notion that anyone might need such a primer. That neatly captures the polarized reception Newsom's music has garnered since the start. Raised in the small town of Nevada City, California, and classically trained on piano and harp, Newsom released her first album, The Milk-Eyed Mender, at the age of 22 in 2004. The sparse and mesmerizing story-like songs drew praise, though her vocals—a high and gloriously unrestrained Appalachian wail—made her as divisive as any singer this side of Björk. "Childlike and pure, sometimes even squeaky when she hits the high notes, I've never heard anything like it before," a reviewer for Tiny Mix Tapes reported at the time. Newsom was briefly grouped with the fleeting "freak folk" and "new weird America" movements of 2004 to 2006, but it soon became clear that her music was a genre unto itself.

For her second album, Ys (pronounced "ees"), she hired a full orchestra to bring to life dense parables about farm animals and fires, some stretching longer than 10 minutes. That album contained lyrics like "Awful atoll / O, incalculable indiscreetness and sorrow / Bawl, bellow," and its cover image depicted Newsom as a medieval maiden, as if she were warning away any less-than-committed listeners.

Accessibility has never been a priority. Today, at the preference of herself and the Drag City record label, Newsom's music is unavailable on Spotify, placing her in a lonely class of artists that includes Taylor Swift and Prince. (She's not sorry about this. She says of Spotify: "It's a business that's literally built from the ground up to circumvent labels having to pay artists.") Spotify, of course, had barely emerged when Newsom last released an album. Have One on Me, a sprawling triple-disc set, might have seemed like another extreme gesture to ward off the unbelievers, but the songs—from the opening plea "Easy" to the devastating farewell "Does Not Suffice"—were the most affecting of her career, with uncharacteristically direct meditations on heartbreak and a voice that had deepened, following vocal warm-ups to prevent a recurrence of vocal cord nodules.

On Divers, that voice is back, but it's what surrounds it that's most immediately striking. With a vast pool of collaborating composers, including Dave Longstreth (Dirty Projectors) and classical composer Nico Muhly, and a wide range of often archaic instruments ranging from clavichords to Marxophones, Divers is Newsom's most richly produced set yet.

Press materials promised an album of "sci-fi sea-shanties and cavalier ballads." The nautical theme is clear—there's an oceanic album cover and a title track about a pearl-hunting romance, with eerie harp arpeggios to capture the sense of drifting underwater. But it's not the ocean that fascinates the songwriter. "It's the line separating sea and sky," she says. Newsom often talks about her work in airy, abstract terms. "I think most of the songs that take place on the ocean are very concerned with that line."

The moody "You Will Not Take My Heart Alive," for instance, opens with an image of "the line of the sea, seceding the coast." Newsom has long puzzled over borders of both love and geography and how they might be traversed. "When you come and see me in California," she sang on Have One on Me, "you cross the border of my heart."

But the final track on Divers, "Time, as a Symptom," brings Newsom back to shore, grappling with loss. "The moment of your greatest joy sustains," she promises the listener, and suddenly the song swerves into a frenzied march of voices, strings and dove calls. The track's gushing refrain calls out for the "nullifying, defeating, negating, repeating joy of life," and the grief fades into the swell of interlocking vocal harmonies.

Those five and a half years might have been worth the wait, all for this song.

Divers is Newsom's most costly work to date (and that's saying something, "cause I made a full orchestral record to [analog] tape at one point") and, by a matter of seconds, her shortest. She spent nearly half her career working on it. Not that its relative brevity makes it seem slight—every lyric sounds dwelled upon, every moment carefully considered. Still, the plan was never to burrow down into a bunker somewhere in the Hollywood Hills and emerge half a decade later with an offering.

"I'm so glad no one told me when I started it how long this particular idea was going to take," Newsom says. "I would have been really discouraged. As it was, I was bright-eyed, idealistic and really excited about this idea and forging ahead, and it just happened to take a really long time to finish."

To hear Newsom describe the making of the album is to realize how meticulous her method is. (She even had her father consult birdwatchers to identify bird calls she wanted to use on the record.) Writing took one and a half, maybe two years, she says casually. Recording the basic tracks took a few months. Then the real laborious process: trying to convey to collaborators how the album sounded in her head. That took a year or two. "There was a lot of doubling back," Newsom explains, "because this is the first record where I've worked with a different arranger or different set of musicians on pretty much every song."

There were nonmusical holdups too. In 2013, Newsom married Samberg, her longtime boyfriend, in Big Sur, California. Then, in 2014, Newsom made her film debut, narrating and appearing briefly on screen as the mystic Sortilège in Paul Thomas Anderson's mega-stoned Thomas Pynchon adaptation Inherent Vice.

This, it turns out, was very much unplanned. Newsom came to know director Paul Thomas Anderson through his longtime partner, actress Maya Rudolph, a friend of Samberg's. At dinner one night, Newsom and Anderson started talking about the book and their mutual love for Pynchon, who was one of her favorite writers in her teens and early 20s.

"A few months later, he texted me and asked if I might be interested in trying an idea," Newsom recalls. "He was fooling around with the idea of having the narration from the book be voiced by a character." She didn't believe she was really being considered for the role. "I think he said, 'I'm trying an idea out. Would you mind recording these lines into your phone and sending them back?' I didn't have a lot of information out the gate. I think I kind of figured that if he liked the idea, he was going to hire a professional actor to do the job."

Then, after being asked to take part in a table read, another surprise: "I got a call from the wardrobe department at Warner Bros. asking for my measurements, and I was like, OK, I guess there's a chance I'm going to be on camera then. But Paul never asked me or told me." Newsom ended up appearing in several scenes. The filming took just five days, but the narration process stretched on for months. Anderson kept rewriting the script slightly. Then Newsom got a cold and had to redo a number of great takes when her voice became hoarse without warning.

It was worth the aggravation, Newsom says. Making a movie was new; it was rejuvenating. Of the final cut, she raves, "I think it's amazing."

The album was largely recorded by the time she began filming, but it hadn't been mixed. "I had a distinct feeling through the whole process of making this record that the thing that would give it its identity, the thing that would breathe life into the album, was going to be the mixing process," Newsom explains. She doesn't listen to any music while recording an album, until the mixing. Then she revisits her favorite albums for inspiration. "Right now, everything under the sun sounds like garbage to me," Newsom admits of this process (though she does declare an affection for Kendrick Lamar's recent To Pimp a Butterfly). "I get ear fatigue, and it's really nice to orient yourself to a complete record that sounds great." For this album, her reference points for mixing were mostly from the early 1970s. She rattles off a list: Richard and Linda Thompson's First Light, Mickey Newbury's Looks Like Rain, Roy Harper's Stormcock, Joni Mitchell's Blue.

She pauses at the mention of Blue. "That record is astonishing. If you just look at it as a technical document, it's incredible. The piano sound that she has on that record—there's no piano that has sounded like that before or since."

She sounds just like a Joanna Newsom obsessive talking about one of her songs.

Newsom knows there's a feverish cult surrounding her. She's unconcerned with the details. She doesn't Google herself, she says. "I don't think it's a great idea for me to read reviews," she says. Nor does she keep a social media presence or much of a public persona outside of the music. She is walled off from the incessant chatter, the daily distractions. When I mention a fashion Tumblr that exists solely to chronicle her outfits—vintage dresses, silver leather heels—she nods in recognition, but says she hasn't looked at it. In February, Pitchfork ran a piece titled "The Atypical Fashion Cult of Joanna Newsom." "I have been made aware of that as well," she says. "It's sweet. It's awesome. But it's probably not the best idea for me to personally read it."

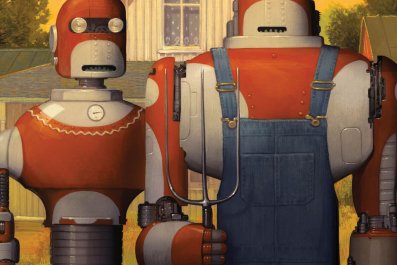

Though her relationship with Samberg has garnered her Emmy appearances and mentions on Us Weekly, she guards her private life. Before we sat down for an interview, I was told she doesn't want to discuss her marriage or her home. The record has much to say about love and loss and places in between, but it is not diaristic. Newsom refers to her songs as being sung by a "narrator," voiced by something apart from herself. "Every single song is narrated by a slightly different entity on this record," she explains. "They're all kind of about the same thing, but they are approaching that collection of themes from different angles." Divers is the first Newsom album not to feature the artist on the cover in some fantastical garb, but "the cover still is representative of the narrator."

I ask Newsom if she would articulate the themes. She refuses, as if I've asked a novelist for the CliffsNotes version. That's a task for the cult, the devoted followers, who'll get to the bottom of Divers like divers for pearls.

"It's all there," she says. "It's all in the record. I feel like for me to summarize it is taking the fun away."