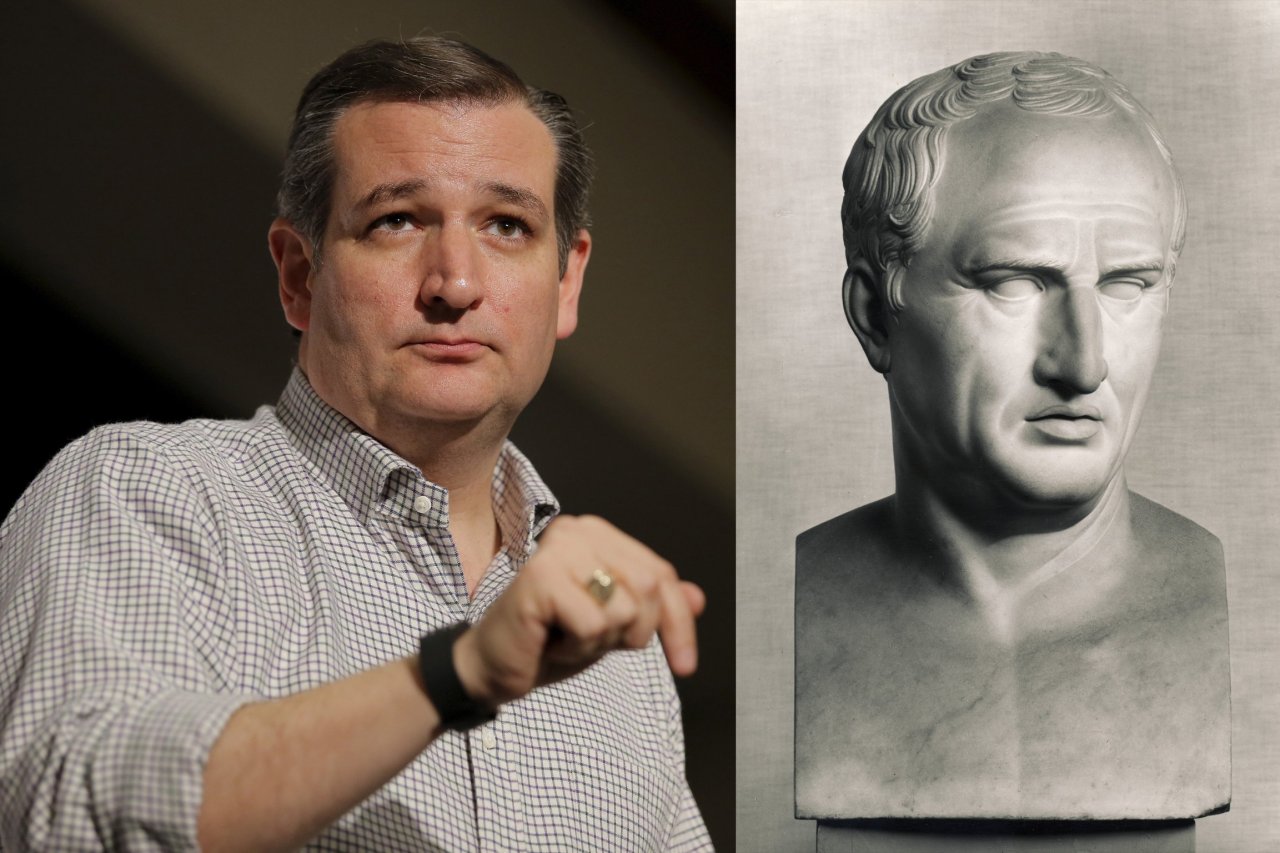

Ted Cruz's onstage appearance with Sean Hannity was going well. It was February 2015, and Cruz, like all the other GOP hopefuls, was at the Conservative Political Action Conference near Washington, D.C., being lobbed softballs by the Fox News talking head. Hannity was playing a little word game. "I'm going to ask you about three people, first words that come to your mind," Hannity said.

"Barack Hussein Obama," Hannity prompted. Cruz took a few seconds. The senator's response was "lawless imperator."

Lawless was no surprise. President Obama's executive orders render Republicans and Cruz in particular apoplectic.

It's the other word—imperator—that puzzled. Imperator is a Latin word, and not one of the handful, like et , cetera , ad and hoc that have made their way into everyday English (though the word was in best picture nominee, Mad Max: Fury Road, as the title of Charlize Theron's character, Imperator Furiosa).

In republican Rome, imperator was a title held by military officers that meant commander—literally, someone who had been granted imperium, or command, by the senate. Later, after Julius Caesar overthrew the Republic and declared himself a god, his heir, Augustus Caesar (also a god), made the title exclusive to himself and to members of his family, the Julio-Claudian dynasty. It was used in place of rex—king—because, while the Romans could stomach being ruled by an autocrat, they couldn't stand having it rubbed in their faces. So more palatable terms, like imperator and princeps were used, at least until the Romans got used to the idea of being ruled by a tyrant.

And the emperors were unquestionably tyrants. It was in this sense that Cruz likely used the word to refer to Obama, according to Robert P. George, a conservative thinker and the senator's thesis adviser when he was an undergraduate at Princeton. "You have to be careful not to attribute to him more than what he's saying," George says, but "I think what he's suggesting is there's just too much of a whiff of the dictatorial, the Caesarian, when any president—and Obama is now doing it—operates by executive orders to legislate, especially when he himself has said he lacks the legal authority."

Ted Cruz knows more about classical antiquity than any of his challengers for the Republican nomination. Every would-be president has their political icons. John McCain said his is Theodore Roosevelt. For Cruz, ancient Rome is as relevant as Ronald Reagan. It's the stage on which the issues he cares most about have unfolded. But in a world where few outside the Vatican speak Latin (and even fewer speak classical Latin, the variant most of the texts from the Republican and early Imperial periods come in), why does Cruz bother with these abstruse references? Sara Monoson, a professor of classics and chair of the political science department at Northwestern, has an idea.

"My own suspicion is it's part of his effort to craft this image of himself as someone in possession of special knowledge," she says. A dog whistle for the classically savvy, in other words. "It's a way of cloaking yourself in a lastingness, in a claim to not be a flash in the pan," she says, "but rather engaged in some kind of deeply important matter that's not going to go away."

Even so, Cruz's esoteric classics references rarely resonate with his audience.

Take, for instance, a November 20, 2014 speech Cruz gave before the senate, on Obama's executive actions on immigration "When, President Obama, do you mean to cease abusing our patience?" Cruz asked. "How long is that madness of yours still to mock us? When is there to be an end to that unbridled audacity of yours, swaggering about as it does now?" He went on: "Shame on the age and on its lost principles. The senate is aware of these things; the senate sees them; and yet this man dictates by his pen and his phone. Dictates."

If Cruz's words sound odd, it's because a Roman senator wrote them, albeit in classical Latin, in 63 B.C. A few changes were made—the word phone appears in Cruz's speech but not, of course, in the original—but otherwise Cruz was faithful to the original speech, which was meant to convince the Roman senate to execute Lucius Sergius Catilina, whom we call Catiline, himself a member of the senate, heir to an ancient but crumbling family. Catiline, the speech alleged, planned to overthrow the Republic and murder a good chunk of his fellow senators. Following the speech, Catiline, scared for his life, fled Rome and marshaled an army. He died at the Battle of Pistoria, near modern-day Tuscany, in 62 B.C.

The senator who spoke the words that drove Catiline into exile and eventually to his death was Marcus Tullius Cicero, perhaps the most famous Roman statesman and orator who ever lived. Cicero had two great political enemies in his lifetime: Caesar and Catiline. If Cruz equates his political foes to Cicero's political foes, is it thus fair to assume that Cruz sees himself as a latter-day Cicero, defending the republic against the usurpatious Obama?

"I'm sure [Cruz] doesn't see himself as a modern-day Cicero," George, Cruz's thesis advisor says. "Anybody who runs for President's got to have a healthy ego in the sense that they have to believe in themselves, but you don't have to believe you're Cicero or Plato or Justinian." Others who knew Cruz during his time at Princeton disagree. "It was my distinct impression that Ted had nothing to learn from anyone else," Erik Leitch, who lived in the same dorm as Cruz at Princeton, told The Daily Beast.

But there are definite parallels between Cruz and Cicero, according to John Wynne, an associate professor of classics at Northwestern University who studies the Roman orator. Both men consider themselves defenders of older, purer orders against the predations of populist tyrants. For Cicero, that meant the looming shadow of empire; for Cruz, it's the shadow of the so-called "Imperial Presidency." And neither man was a native son of their respective empires: Cicero was born not in Rome, but in Arpinum, about 120 kilometers southeast, and was thus excluded, by virtue of his foreign birth, from the highest class of Roman society. Similarly, Cruz was not born in the United States, but in Canada to a Cuban father and an American mother (Cruz renounced his Canadian citizenship in 2014). Further, both men received sterling educations. Cicero had the best tutors money could buy. Cruz went to college preparatory schools in Texas before attending Princeton, then Harvard law school.

It's not a perfect analogy. Cicero, for one, was well-liked by his peers. Cruz is not. Foreign Policy called him "the most hated man in the senate" and former Republican presidential hopeful Bob Dole has said he likes all of the Republican candidates this time around—"except Cruz." And, though Cicero was a conservative like Cruz, he agreed in principle with many of Catiline's more populist reforms, like debt forgiveness. What he disagreed with were Catiline's methods—debt relief through the murder of lenders, for instance, didn't sit well with the orator.

But, unlike Cicero, Cruz isn't purely concerned with the opinions of the optimates (what Roman society called its most well-respected members). His references to classical antiquity aren't all meant for the ears of the traditional donors class. Take, for instance, Cruz's common refrain on gun control: "Come and take it!" The phrase was supposedly spoken by the defenders of the Alamo after General Santa Anna of Mexico demanded they give up the cannons guarding the fort during the Mexican-American War. The phrase has become a mantra among the anti-gun control crowd, and the defenders of the Alamo are portrayed as heroes fighting for their God-given freedoms against an overweening dictator.

Of course, the Alamo defenders were fighting in defense of slavery, and Santa Ana was protecting his country's territory. And, notably, Santa Anna did come and take it: the Alamo defenders were slaughtered almost to a man. But the phrase appeals to more than just diehard Texans. It also triggers a response among Cruz's classics-savvy followers, because it actually harkens back to classical antiquity. Supposedly, it was first spoken by the Spartan king Leonidas at the Battle of Thermopylae (on which the movie 300 is loosely based). The Persian king Xerxes demanded Leonidas cede Sparta, to which he famously responded, "μολὼν λαβέ"—come and take. The outcome that time was a bit different: While the Spartans were slaughtered, the Persians couldn't take Sparta. But the outcomes don't really matter. What matters is how Cruz channels the Spartan king's belligerence to sway voters, both well-educated and less-so. And it's not unfair to suggest that the notion of the West defending its culture and society—by force if necessary—from an Eastern potentate probably resonates with most Cruz supporters, as well.