A video showing the hideout of Joaquín Guzmán Loera (aka "El Chapo"), filmed October 6 by the Mexican navy and broadcast by the Mexican newspaper El Universal, is incredible for its details. Films shot by law enforcement in the hideouts of mafia bosses are usually very similar—there's great excitement, even when, as on this occasion, security forces suspect that the boss and those who helped him while he was on the run are long gone. There's the care taken not to touch anything: That's why they usually enter with video cameras rolling, so that everything is documented; so that nothing, even the smallest clue, can be removed or misplaced. You can always hear the breath of the person behind the camera, who is usually filming with one hand and holding his weapon with the other.

The video you can watch above of the unsuccessful raid on El Chapo's hideout three months before his capture opens with an aerial shot of Las Piedrosas, a town in the Mexican mountain range called Sierra Madre Occidental. Then it cuts to the events on the ground: Armed men come out of a helicopter, hunting for something. When they get inside a one-story building in the middle of a clearing, we can see a spartan kitchen, spartan like the rest of the dwelling. And then a room with raw plaster walls, and a clothes rack with brightly colored shirts, a dozen of them. The first, closest to the door, seems to be the exact one El Chapo had worn only four days earlier, during an interview with actor Sean Penn for Rolling Stone. (The brand is Barabas.) The flat-screen TV on the wall, along with the shirts, seems surreal in such simple surroundings.

And then we see two beds made of concrete, one of which is covered with a dark sheet. On that bed, there is a pale duvet, a blue backpack, some toilet paper and my book about the global drug trade: ZeroZeroZero, a significant part of which is devoted to Mexico and, therefore, to El Chapo. To his rise, to his business endeavors and to his spectacular criminal career, but also to his cartel's internal struggles and to the need for a successor.

El Chapo's prison breakouts don't surprise me as much as his arrests, which seem to owe more to the internal demands of the Sinaloa cartel than to the investigative work of the Mexican police. In the past few years, while the boss has been in and out of prison, the cartel hasn't suffered significant upheaval because in its upper ranks a strong, unyielding and much more discreet leader remained: Ismael "El Mayo" Zambada, the brain and, most likely, new leader of the organization. The command certainly will not be passed on to El Chapo's sons, Iván Archivaldo and Jesús Alfredo, who seem to be victims of exhibitionism with no economic vision, traits that are a poor fit for a mafia boss. Fond of luxury, nice cars and beautiful women, they use social media to send threatening messages to the government and to express their blustering desire to show off. However, they appear to have more followers on Twitter than in the organization.

In this context, El Chapo's arrests and escapes seem like a theatrical spectacle, the plot of which we must strive to interpret beyond the government's Twitter proclamations.

Mafioso Reading List

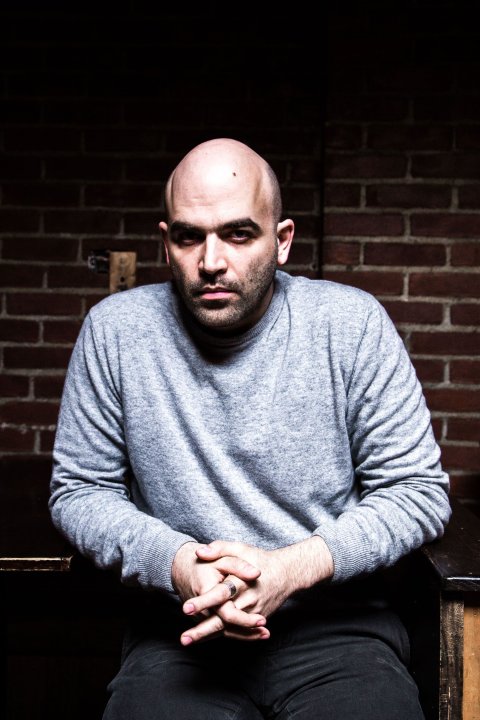

When El Chapo was captured in January and the October video was released, I was in Italy, where I am guarded at all times because of threats to my life over my first book, Gomorrah, about the Italian Mafia. Italy's Carabinieri (military police), who keep close track of anything that involves my security, woke me up in the middle of the night to tell me about the film.

I admit that my first reaction was surprise. Was El Chapo in such a hurry to get away that he didn't touch anything, or did he want to leave clues behind? I didn't wonder about it much, but I've heard a great range of hypotheses about why my book was there. One theory concerns my appearance on Mexican TV: In interviews after El Chapo's previous capture in February 2014, I had pointed out the pressing need to extradite him to the United States. Perhaps his lawyer procured the book to offer him further information about me and what I had written about him.

Some people say he was worried about the ZeroZeroZero TV series, a French-Italian joint venture currently in the writing stage and due to air in 2018. Others say the book belonged to his son, who had seen my interview on CNN. Other hypotheses range from speculation that Penn gave it to him to the absurd suggestion that El Chapo was a source for my book.

Regardless of the theories, I felt as though my work had been sullied, as though it had attracted the attention of the wrong person. El Chapo knows El Chapo's life. He knows cocaine's power. He doesn't need me to explain those things to him. My book was directed at others, and yet I had to once again contemplate the natural interest all bosses have in knowing and controlling what is said and written about them. And not only that—I also had to account for the habit of fugitive bosses to read, to keep books with them, to study, to listen to classical music. Fiction has accustomed us to the idea of mafiosi as criminal animals, mostly uneducated, but that's never been the case, and today, more than ever, it's not the case.

Gabriel García Márquez's One Hundred Years of Solitude and a book by Italo Calvino were found in the bunker of Pasquale Condello, boss of Italy's 'Ndrangheta mob, and Camorra boss Francesco Schiavone, known as Sandokan, had dozens of essays on Napoleon. Cosa Nostra boss Pietro Aglieri read only theological works, favoring Saint Augustine. The Camorrista Raffaele Cutolo had Hobbes, Plato's Republic and Hitler's Mein Kampf in his cell.

Mafia bosses are experienced businessmen who read, examine, study, analyze and try to use the information circulating about them to construct a twin narrative. On the one hand, it must present them to civil society as men who have tons of women and money and are forced into criminal choices by the world's iniquity. On the other hand, it must give a forceful and unequivocal message to their members and rivals alike: I am the strongest and most brutal. I punish and seek revenge. They write about my monstrosity, so fear me.

That's why, when approaching a project dealing with criminal power, the first task of a journalist, screenwriter and even a director is to read. One must study not only criminal history but also, and above all, the ways in which mafias have learned to communicate with their members and with the rest of the world. Because mafias do communicate, continually, utilizing the most popular channels, including social media, to create consensus, to legitimize themselves and to terrorize.

It's no surprise that El Chapo was thinking about a film to tell his story; it's no surprise that he wanted to meet Sean Penn, a famous Hollywood actor. This was not about vanity but about his need to come out in the open, to tell his story, to send a strong signal: I'm alive. I'm here. I'm not hiding like a rat. I'm the strongest. Bosses want movies about themselves not because they think they can improve their image but because they know it is the only way to make others clearly perceive them as the real main characters of this world. In an article, or during a trial, a boss is reduced to only one dimension. But in a film or a TV series, even when the protagonist is a murderer, a criminal, he may nevertheless be observed from multiple points of view. Michael Corleone, Tony Soprano and Tony Montana are all lead characters who thrill audiences because they are complicated, strong and vulnerable.

When Rolling Stone published Penn's interview with El Chapo, the reactions were immediate. The first and most common was annoyance: What does Sean Penn have to do with the Mexican mafia? Why him? Why not a journalist or writer who works on these issues? And why did Mexican actress Kate del Castillo arrange the meeting? Why didn't a lawyer act as mediator? El Chapo's desire to stand out and be interviewed and the plans for a film all suggest an apparently vain man who is more likely to follow his whims than to take care of business deals.

And yet to anyone who read the interview, the real motive for the choice is clear: El Chapo did not want a difficult interlocutor. Even at the risk of seeming ridiculous, he wanted to tell his story, to talk without being contradicted and without having to respond to sensitive questions about the organization of the Sinaloa cartel, his assets or the code he lives by.

If you asked me whether I would have interviewed El Chapo while he was a fugitive, I would respond, "Maybe yes, if I had had the real chance to do so without being used as a channel for messages." Penn's error was not in doing the interview, nor was it that he refrained from judgment. It was arriving unprepared, unable to ask complex questions. It was a lack of awareness.

And that lack of awareness also prevented him from understanding that joining the ranks of writers who take on mafia stories doesn't make you a better person. It doesn't grant you professional recognition or personal prestige. On the contrary, it closes doors, and it exposes you to constant criticisms, not the least of which is that of speculating, exaggerating and inventing.

Cutting Deals With Beasts

The reality of the global drug trade is so complex and extreme that it sometimes seems unbelievable. Today, Mexico is the center of this world, and El Chapo is its most famous boss. He is living proof that calling the Mexican cartels "narcos" is inaccurate. They are mafias. The difference is not always clear to those reading the news, but it can be clarified like this: Gangsters are motivated by money; mafiosi are driven to construct a system of power (in which money is only one tool).

Understanding the difference is an important step toward grasping why El Chapo is interested in knowing what the world says, thinks and writes about him, as well as why the interview granted to Penn held immense value for him. Why he was interested in producing a film, something that might have compromised his ability to remain on the lam. Why, through his lawyer, he had asked Patrick Radden Keefe to collaborate on a biography. The author and journalist refused, and, writing in The New Yorker, he reflected on a fundamental point: He needed the freedom to be able to talk about the man Joaquín Guzmán Loera and not about El Chapo—that is, about the myth.

This distinction is important, especially with respect to the role the United States could, but does not, have in the fight against organized crime. Often governments are moved to act by pressure from public opinion, but in the U.S. public opinion is clueless when it comes to understanding this criminal phenomenon. Americans have a partial vision of mafias and drug trafficking because in the U.S., unlike Mexico or Italy, they don't kill journalists, they don't kill priests, they don't kill judges. And this creates a public perception of the mafia as an organization that is merely theatrical, one that doesn't present a threat to democracy or hold power over life and death.

The biggest mistake you can make is to believe that mafia bosses are simply war machines or characters of folklore, because in doing so you underestimate them. The criminal economy is a winning economy; the drug trade totals more than $300 billion a year worldwide, so these bosses inhabit the very top of the pyramid. In the United States, the bloodshed is nothing like that on Mexico's scale; the killing is mostly internal, but the drug lords pollute the economic system:

- In 2012, banking giant HSBC agreed to pay a fine of $1.92 billion for money laundering linked to drug cartels. Between 2007 and 2008, HSBC Mexico moved $7 billion to the American branch of the bank, a large part of which came from the Sinaloa cartel.

- In 2009, Antonio Maria Costa, executive director of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, said there were clear signs that during the global financial crisis many banks were saved thanks to liquid capital from drug trafficking.

- In 2010, Wachovia Bank agreed to pay the federal authorities $160 million (the result of forfeiture and a fine) for failing to apply the proper anti-money-laundering protocols and allowing transactions linked to drug trafficking. Wachovia, like HSBC, was used by the Sinaloa cartel to launder hundreds of millions of dollars.

The drug lords' goal is to reinvest drug trafficking revenue in legal activities. And the American banking system is completely defenseless against this aggression.

Additionally, there is a direct link between the survival of Central and South American drug cartels and the United States' enforcement strategy. Consider the history of El Mayo's son, who, in contrast to El Chapo's offspring, seems to be the one with the characteristics of a mafioso chief. His story is worth knowing precisely because it concerns the United States.

Up to his arrest in 2009, Vicente Zambada Niebla, known as "El Vicentillo" ("Little Vincent"), was a prominent member of the Sinaloa cartel until he was extradited to the U.S. in 2010 to face drug trafficking charges. Once there, he started making devastating statements. For example, he talked about the existence, since the end of the 1990s, of a deal between the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) and the Sinaloa cartel in which the anti-drug agency allegedly guaranteed immunity to the cartel's leaders in exchange for information about their rivals.

Zambada's trial was delayed multiple times, and in the end he negotiated a plea bargain, pleading guilty and receiving a reduction in his sentence (which could be cut to as little as 10 years, compared with a life sentence) in exchange for not contesting a forfeiture judgment of more than $1.37 billion and pledging to collaborate with U.S. authorities. His story about the deal brokered in the '90s never convinced me in its entirety, but if the DEA did strike an immunity deal with Zambada and the Sinaloa cartel, it would mean the U.S. essentially agreed to allow the cartel to operate undisturbed in Mexico as long as it was subdued on U.S. soil. This is the kind of flawed logic known as the "poisoned well"—that is, we poison the wells in Mexico to obtain clean water in the U.S.

The events surrounding Little Vincent's stay in the U.S. demand careful reflection on the future of El Chapo if he is extradited. First of all, even if his lawyers don't put up a fight, the extradition will take at least six months, a period during which Mexico certainly wouldn't be the most secure place for guarding a criminal of his caliber: He could escape again, or he could fall victim to an internal feud behind bars. Then, if he was extradited, the United States would have to prove itself capable of handling El Chapo, granting him a fair trial and keeping him secure in prison.

Even more important would be to prevent him continuing to rule the cartel from a prison cell. U.S. authorities would also have to resist the temptation of doing a deal, of pursuing domestic peace at the expense of combating drug trafficking in Mexico. It won't be easy, but it is essential to avoid making such a pact with El Chapo, to understand that a life of crime, a life on the run, a life spent trusting no one and always being ready to sacrifice anyone, including one's own children, transforms a man into something extremely dangerous and decidedly inhuman.

The End of What?

Immense power, infinite assets: All that is over for El Chapo, at least for now. In January, another video was released, this time filmed in another of his hideouts. A video camera shows us the places where the Mexican boss spent his final moments of liberty. He's not in the shot. In the shot, there are armed men, weapons firing, shouts, heavy breathing and confused excitement. Again. The video camera frenetically darts around to show all of the exits; nothing can be left to chance. And then another video, very short: A bare-chested El Chapo is transferred from a car to the helicopter that will bring him back to prison.

The Sinaloa cartel's No. 1 man is once again in captivity. We don't know for how long, but we can follow the moves made by his cartel, which must reorganize, and quickly. Who will succeed El Chapo? His right-hand man El Mayo? And will El Chapo's sons sit around and watch that happen, or will they begin a bloody feud?

And what can we do? What is our role in all of this? To observe, to be vigilant, to pay attention and to never quit asking questions and looking for answers. To insist that everything be brought into the spotlight because it's in the shadows, in the gray areas, where the most terrible pacts are signed.

Roberto Saviano is the author of the books Gomorrah, about the Neapolitan Mafia, and ZeroZeroZero, about the global cocaine trade. Since the publication of Gomorrah in 2006, he has lived under police protection because of threats to his life by the Camorra. This article was translated by Kim Ziegler.