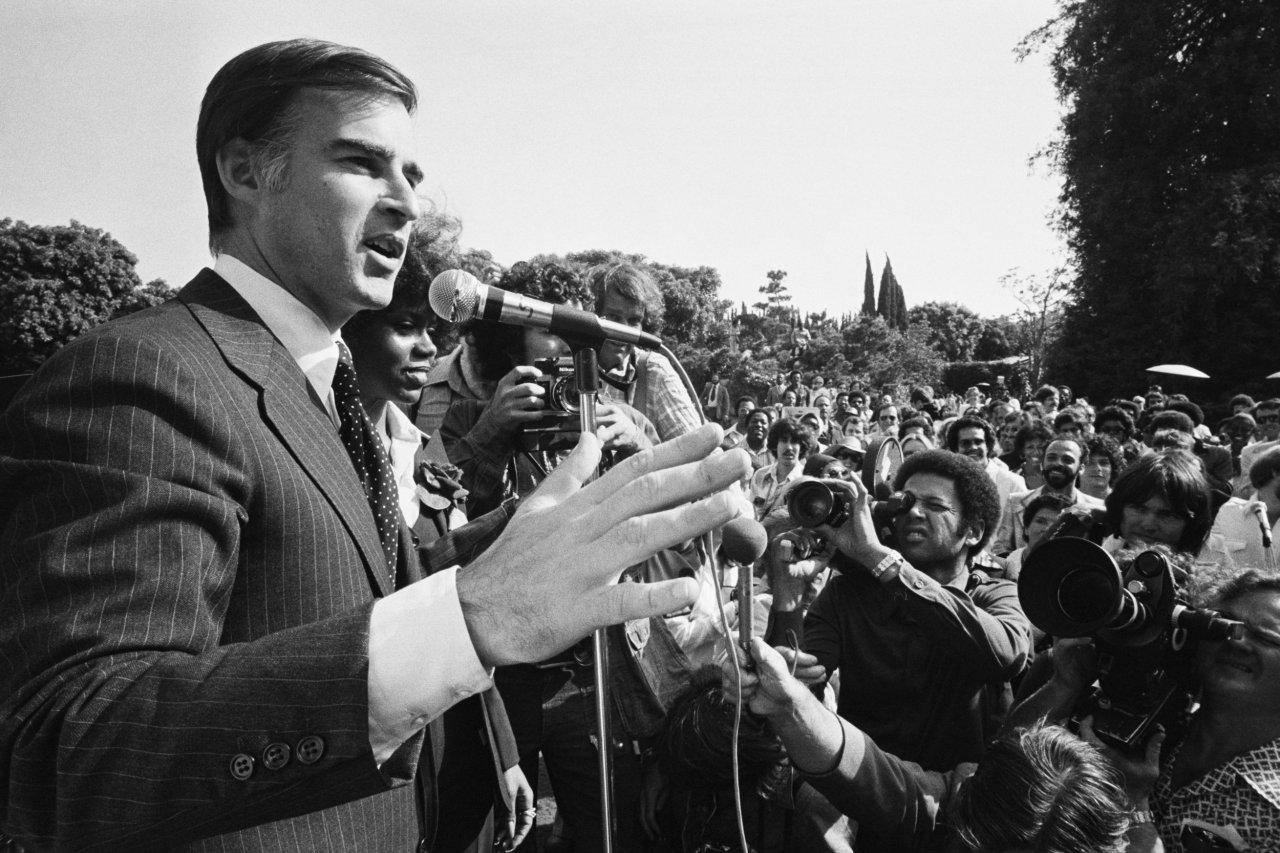

Polls are closing across the South and Midwest, and the chemical cloud of Donald Trump's hair spray hangs over the nation as I make my way through downtown Sacramento to the California State Capitol, one of those rare municipal buildings that is precisely as grand as it ought to be. Inside that alabaster pile, I stride past an enormous statue of a golden bear—the state's symbol—perhaps placed there to remind all who enter of the Bear Flag Revolt, which rendered a part of Northern California a sovereign nation in 1846. (Much like Texas, California is a state that contributes greatly to American identity by celebrating an identity that is entirely its own.) Beyond the ursine sentry is a waiting room, where an appropriately sunny aide invites me inside to meet the man many thought would have been the perfect Democratic presidential candidate for 2016: California Governor Edmund G. Brown Jr., or, in keeping with the Golden State's famous informality, Jerry.

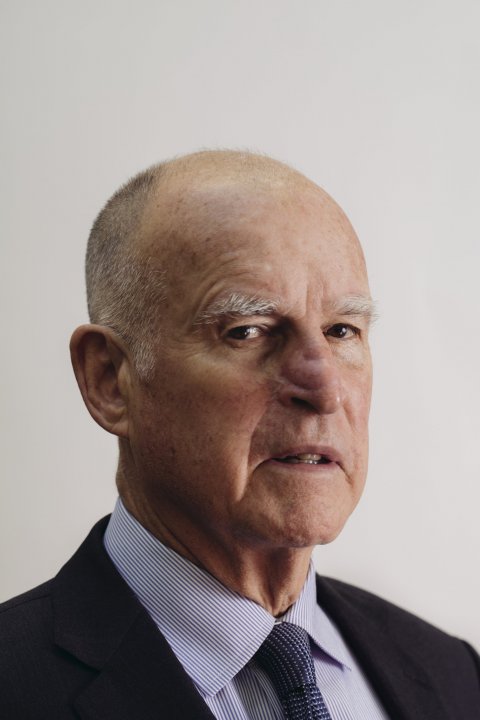

Jerry Brown is the kind of 78-year-old you fear might run the mile faster than you do. Not that he has escaped time's relentless steamrolling any more than the rest of us: He is bald now, the ebony mane he sported on the cover of Newsweek in 1979 (with then-girlfriend Linda Ronstadt at his side) reduced to a low gray crescent. A hillock of smooth skin on his nose is evidence of plastic surgery that followed the removal of a cancerous growth. There was another such growth on his ear, as well as cancer of the prostate. The last of these was announced to the public in late 2012, as Brown was celebrating the passage of Proposition 30, a ballot measure sanctioning what the Tea Party claimed no red-blooded American would ever countenance again: higher taxes.

Brown is also the kind of 78-year-old who has not forgotten his early Jesuit training, with all its injunctions against vanitas. The office in which we now sit has barely enough pomp to suit a first-term legislator from Yuba County. While his cloistered days are long gone, forays into Zen Buddhism and Mother Teresa's India have reminded Brown about the impermanence of earthly things. Beyond informing his interior decorating, Brown's intellectual affinity for austerity has helped him pull the state out of a fiscal canyon about $27 billion deep.

Spartan though it may be, Brown's office offers rich reminders of the historical currents that have brought him here once again, after two far less successful terms as governor in the 1970s. Examples include the small framed photograph of his father, who also served as governor of California, with John F. Kennedy, and an issue of New West magazine from 1976 with a cartoon rendering of himself on the cover (he had been elected governor only two years before but was already battling Jimmy Carter for the Democratic presidential nomination). New West called Brown a "philosopher-king" who was "off to a flying start." There is also, near the door, a wooden sign from the ranch his great-grandfather August Schuckman built in Colusa County: "Venado 1855," it says. California has been good to Brown and his forefathers, but they have also been good to California.

It is only the first day of March, but it feels like the middle of summer, the temperature well into the 70s. Brown says the winters were never this warm before. The previous fall, he had attended the United Nations climate change conference in Paris, where he touted California's ambitious goal of radically reducing its reliance on fossil fuels. Meanwhile, nearly all the men competing for the Republican presidential nomination were vociferously denying that climate change exists. "There's no doubt on the part of serious scientists that this is a real problem," an exasperated Brown tells me. It is also accepted by both the supreme pontiff of the Roman Catholic Church and the Communist president of China—but not by the junior senator from Texas, who has suggested it is a liberal conspiracy.

"The Republican Party is very ideological," says Brown, like a doctor who sees the disease but not the cure. "They're very off the deep end."

Brown, by contrast, is far too inquisitive and restless for ideologies, which is why some sought to draft him into a 2016 presidential race in which Trump and Bernie Sanders have been the two candidates engendering the most enthusiasm, each offering unrealistic ideas involving border walls and class revolt. If it is true, as New Jersey's hapless chief executive, Chris Christie, claimed, that governors know best, then Brown knows better than anyone, presiding over a state that proudly adheres to the popular stereotype of California social liberalism, but not to the more damaging one of Democratic profligacy. Brown is the rare progressive who can balance the books, who can sell fiscal restraint to Bay Area liberals and gay marriage to Orange County evangelicals.

"If Jerry were even 10 years younger, he would've been on everybody's list," says Ethan Rarick, associate director of the Institute of Governmental Studies at the University of California, Berkeley. Brown is three and a half years older than Sanders, but age isn't everything: While the unkempt socialist has the grumpy demeanor of a South Florida retiree wondering who forgot to flush the poolside bathroom, Brown is both physically fit and mentally astute, fighting off senescence with regular trips to the gym. In his free time, he has been reading about nuclear disarmament. Never the retiring kind, Brown is not ready for retirement.

Nor does he seem especially enamored of the current crop of presidential candidates. He calls Trump—on the day of his Super Tuesday rout—"pretty wild" and says his claim that he'll make Mexico pay for a border wall is "not a serious statement." About two weeks after we met, as the golden-haired man-child drew ever closer to the Republican presidential nomination, Brown joked at a dinner for labor organizers that he would wall off his state if Trump wins.

Brown is more conciliatory toward Hillary Clinton, whom he calls "a very powerful force" who "fills up a lot of the room for the Democratic primary." That sounds less like an endorsement than a concession, which should be no surprise: In 1992, when Brown undertook his third and final bid for the presidency, he sparred with Bill Clinton over improprieties involving her law firm. "You're not worth being on the same platform as my wife," Clinton thundered back, the two men thrusting fingers at each other as if they were lances.

Brown watches Hillary Clinton's plodding ascent of Nomination Mountain with bemusement, telling Chuck Todd of NBC's Meet the Press last summer that her email scandal is "almost like a vampire," one that possesses a "dark energy" and "mystique" Clinton would find hard to extirpate. And she has. Earlier this month, Politico suggested that Clinton might make Brown her running mate, though he has previously said he is "not particularly" enthralled by the vice presidency.

Whether on climate change, government spending or Clinton's email servers, Brown has a Cassandric quality, a mixture of prescience and alarmism that was disconcerting when he was young but is soothing now that he is old and can say "I told you so" with an unthreatening demeanor. The best thing to say about Brown is also the worst thing to say about him, and it is the thing that has always been said about him: He is way ahead of his time.

Quixotic Parsimony

The portraits of the state's past governors hang on the third floor of the Capitol, and they invariably show solid men aglow with the promise of the California dream: Earl Warren, Ronald Reagan, Arnold Schwarzenegger. One painting, though, is unlike all the others, the one of Brown by Santa Monica painter Don Bachardy to commemorate his first two terms as governor. Rendered with wide, disjointed strokes, the painting shows a young man troubled by something in the distance—as if anxious by forces beyond his control, perhaps haunted, Hamlet-like, by the spirit of his father.

Brown was only 36 when he first won the governorship, taking over the post from Reagan, who had defeated Brown's father, Pat (Edmund G. Brown Sr.), in his bid for a third term in 1966. The younger Brown did not seem a natural for the world's second oldest profession, as Reagan once deemed politics, having spent three years in a Jesuit seminary before decamping for the secular maelstrom of Berkeley in 1960 and, after that, Yale Law School. His first elected position was to an obscure community college governing board in Los Angeles, which he quickly used as a ticket to Sacramento, winning the secretary of state election in 1970.

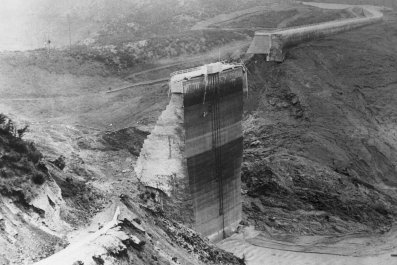

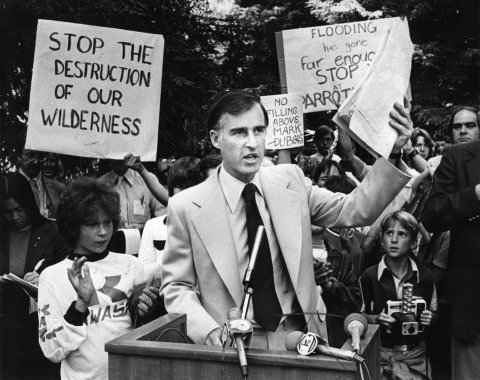

The family name helped elevate Brown to the governorship. Once in office, though, he distanced himself from his father, a classic big-spending Democrat who made huge outlays to fund the State Water Project, expand the University of California system and build new highways. Brown was philosophically closer in some ways to Reagan, with his conviction that government could not always help those it governed. Confronted in 1976 with his parsimony, he declared: "As you know, I don't like to spend money, but it's not because I'm conservative. It's just because I'm cheap." He famously eschewed the governor's mansion and drove himself to work in a blue Plymouth Satellite.

Beyond these shows of thrift, his accomplishments were few. "The first time around, a lot of his term was focused on undoing what his father had done, including the system of higher education," says Sherry Bebitch Jeffe, a professor of public policy at the University of Southern California. Brown made groundbreaking appointments of women, gays and people of color, while passing important environmental legislation, but eight years in office yielded no signature achievement. And while the 1976 run for the presidency was thrilling, the 1980 one was quixotic, leaving Brown with the battered reputation of a young man with more ambition than follow-through. Rarick says a sign of Brown's unpopularity was his 1982 senatorial campaign, which served as referendum on his governorship: Brown lost that contest to San Diego Mayor Pete Wilson by half a million votes.

Another defeated politician might have gone into lobbying or consulting, shilling for some maligned industry or bloodstained nation. Brown went to study Zen Buddhism in Japan and work with Mother Teresa in India, in a return to the spiritual questing of his earlier years. Sacramento, it seemed, had purged Brown of any remaining enthusiasm for politics.

Oaktown's Finest

The Oakland Military Institute College Preparatory Academy sits in the flatlands of that ever-ailing city by the bay, in a neighborhood of few trees and low houses not yet invaded by those whom Uber and Facebook have made obscenely rich. OMI is a cross between a charter school and a boot camp: drills, uniforms, rules upon rules. The school's Latin motto is age quod agis, which means "do what you are doing," a traditional Jesuit exhortation. Here, behind plastic green fencing, is an early relic from the second coming of Jerry Brown.

Brown became mayor of Oakland in 1999, a move akin to President Barack Obama declaring that, after he vacates the White House, he wants to be a Chicago alderman. But in some ways, Brown's decision was even more fantastical: Oakland is a stronghold of African-American culture that gave rise to the Black Panthers and had not seen a white mayor since the 1960s. A battered but proud city, it is eternally suspicious of carpetbaggers.

OMI is a symbol of the two terms Brown spent as mayor of San Francisco's moody, complex and far poorer sibling. He supported charter schools before they were a fashionable New Left cause, starting two. And though he'd always had what Rarick calls a "law and order streak," his pro-police stance was a risky one in a city where, not all that long ago, the Panthers had followed police officers with rifles drawn. Further signaling an impatience with the status quo, he courted private developers in an effort to attract 10,000 new residents to Oakland's ghostly, abandoned downtown. Some complained then, and some complain still, but nobody could have foreseen Oakland celebrated as the coolest place since Brooklyn. Back when he had been governor, all those years ago, he had preached "creative inaction." Now he yearned to get things done.

Brown clearly retains an affection for Oakland, the way you might for a lover whose time has come and gone. Before our meeting, he had just returned from the house he and his wife, Anne Gust Brown, own in the Oakland Hills; the long, plain desk in his Sacramento office comes from his loft in Oakland, which was salvaged from a Sears building. Down the street is another Sears building, soon to become an East Bay outpost of Uber.

Above all, he learned a lesson that the creatures of Capitol Hill would do well to absorb: "People don't like squabbling at City Hall."

The eight years Brown spent in Oakland were successful enough for him to ponder a return to Sacramento, though not because he wanted to rescue another down-on-its-heels city. He ran for California attorney general in 2006, touting his crime-fighting credentials. Brown won that election and used his new position to frequently advocate for environmental causes.

In 2009, Brown made an announcement that would have astounded the most those who know him the least: He would run for governor once again. His first governorship had come in the wake of a Hollywood Republican; so would this one, if he managed to pull off an improbable victory. Or maybe not that improbable. The housing crisis had hit California hard, making Brown's famous austerity oddly fitting, 35 years after it had first been foisted on the state. His opponent was the former eBay executive Meg Whitman, who would spend $178.5 million on the race, yet would be largely undone by the revelation that she'd employed an undocumented immigrant as a housekeeper. Many figured that Whitman had long known about her status, only firing her when the looming election forced her hand. Whitman issued the expected denials, and the housekeeper fought back, announcing to the media, "I felt like she was throwing me away like a piece of garbage."

The Los Angeles Times wasn't exactly giddy about Brown's return to Sacramento but endorsed him anyway, telling its readers Brown was "a sort of grizzled mechanic of the state's failing machinery. He knows which parts can hold out a few more weeks, which rattles can be ignored and how much tension the timing belt can handle before it fails."

Brown won like he usually wins: easily.

Uplifting Doom

California had aged too, and not all that well. "California is no more," declared the critic Saul Austerlitz in 2010, writing in The New Republic. "The state, last I checked, is still there, hugging the Pacific Ocean, but the dream of California—of sunshine, of fresh opportunity, of unbounded freedom—has withered. It has been perhaps irreparably shrunken by decades of poor financial planning, bad politics, and a maddening electorate demanding more while offering ever less." Two years later, long after the Great Recession had run its course, a campaigning Mitt Romney compared California to Greece, which was then in the midst of a protracted meltdown.

Today, the much more apt comparison would be to Germany: a smoothly functioning social democracy that couples technological avant-gardism with liberal social norms and fiscal restraint. Both California and Germany welcome immigrants, even as xenophobic neighbors erect fences. Both are flush with cash. If it is true that California is, as the historian Carey McWilliams called it, "the great exception," then it is also the exception that tends to become the rule, whether in cultural attitudes or technological innovations. Ohio may be the mother of presidents; California is often their tutor.

Brown is at work on two major infrastructure projects: the high-speed rail between Southern California and the Bay Area and the Sacramento River tunnels, which are supposed to alleviate the state's perpetual water woes. But though these would become permanent features on California's face, they pale in comparison with his climate change efforts, which culminated in his star turn late last year at the United Nations conference on climate change. California has been central to the creation and promotion of the Under 2 MOU, a memorandum of understanding that stipulates signatory nations and jurisdictions will work to keep global temperature increase from pre-industrial levels to under 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit). He has also instituted a cap-and-trade program for carbon emissions; the recent legislation known as SB 350 commits California to having renewable sources meet 50 percent of its energy needs by 2030. To meet this goal, he has promoted the aggressive expansion of utility-scale wind and solar power.

Some in the environmental movement, however, praise Brown's climate change leadership but worry that it obscures grave shortcomings. Some call him "Big Oil Brown," pointing to what they see as his close ties to oil and gas companies. His 2011 firing of two oil-industry regulators continues to hound Brown, as does his refusal to close the Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant. His support of hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, to extract natural gas, has further frustrated greens who see his policy positions often clashing with his public persona. "Brown is not a green governor," says Daniel Hirsch of the University of California, Santa Cruz, where he heads the environmental and nuclear policy program.

There are other criticisms. Some on California's vociferous left have called on the stingy governor to spend more on social programs that might benefit the young, the sick, the homeless and the poor. "California has turned the corner. But not every Californian is feeling it," complained a Democratic legislator from San Diego earlier this year.

Brown's critics can rest assured that he has heard them; he just won't heed them. When I bring up this line of complaint, Brown quickly counters that the next recession could cost California $55 billion, so to spend now for new programs would be foolish. "So you pump them up, and then you deflate them," he says with something that could be either impatience or condescension. "That doesn't make any sense." Although Brown signed a bill this spring implementing the highest minimum wage in the country—$15 per hour—he did so only at the prodding of labor unions. The move is revolutionary yet cautious, in that it doesn't actually take full effect until 2022.

Those trying to make sense of Brown's pessimistic view of the state's future note his friendship with the Stanford philosopher Jean-Pierre Dupuy, a theorist of the apocalypse who believes that telling people about the worst thing that could happen might actually make them act in a way that prevents it: instead of the audacity of hope, the efficacy of despair. In a recent op-ed, close California watcher Joe Mathews wrote that " Brown's famous skepticism of new programs makes sense if you believe, as Dupuy argues, that man is blind to the consequences of his own progress. Brown's focus on avoiding catastrophes—including his rainy-day fund and his crusade on climate change—reflects Dupuy's 'prophet-of-doom' calls."

Brown's climate change crusade makes obvious sense when seen through this lens of existential dread. Instead of appealing to the moral rightness of cutting greenhouse emissions, he invokes a horrifying image of a planet ruined by our ignorance. "Human beings are developing the capacity of unimagined impact," he says. Here, philosophy meets politics, for by raising the stakes, Brown lowers objections.

He recently finished reading Philip Taubman's The Partnership: Five Cold Warriors and Their Quest to Ban the Bomb and references atomic warfare several times during our conversation, as if it were a threat that might materialize by week's end. He worries about India and Pakistan in a way that I imagine Governor Greg Abbott of Texas does not. A perfect summer day in winter's midst is not, to him, a reason to rejoice but, rather, to fret over the parched California land and the warming Pacific Ocean and so much else. Out on the Capitol green, there are people happy to bask in the afternoon sunlight, but Brown is constitutionally incapable of joining them. "It's very foolish to think the world's just going on its merry way," he says, "because it isn't."

Hi, Taxes!

In the popular imagination, California is a redoubt of true-blue conviction that stretches between San Francisco and Los Angeles. Against this bulwark, all Heartland conservatism shatters. The truth is more complex in this state that has produced some of the nation's most famous Republicans: Nixon, Reagan, Schwarzenegger, Fiorina. The coast is indeed a liberal stronghold, but inland California can be as red as Wyoming.

Joel Kotkin, an urban studies scholar at Chapman University in Orange County, loves California like only a native of outer Brooklyn can. The California he loves, however, is not the one Brown envisions. Kotkin, who came to California nearly 50 years ago to study at Berkeley, tells me he is a "great admirer" of Brown's father and retains favorable impressions of Brown's first governorship. "He was very interesting in those days," Kotkin laments. "He was very eclectic." He does not have kind words for the latest iteration.

The climate change crusade of Brown's more recent governorship, Kotkin charges, has been a costly distraction from the business of governance. "It's consuming him; it's consuming the state," Kotkin says. "Why should the people of California pay for Jerry Brown to be the high priest of climate change?" Kotkin says new climate change regulations have increased the cost of housing while driving out industry, twin forces that are far more likely to punish working-class Hispanics in Modesto or rural whites in Modoc County than the landed gentry of Los Angeles or San Francisco. "Nobody thought he would become so fanatical in his old age," Kotkin bemoans. Then again, nobody thought he would be governor again either.

It is true that people are leaving California and that the cost of business is, indeed, much higher there than elsewhere. The taxes are higher too, in part thanks to Brown. But his approval rating stands at a very solid 60 percent. "He's made no major mistakes," says California historian Kevin Starr, who puts Brown in the top echelon of the state's governors. Like Brown, Starr is a graduate of St. Ignatius College Preparatory, a prestigious high school in San Francisco. Starr was a freshman in 1954, when Brown was running for the presidency of the senior class. He hasn't stopped running since.

Rainy-Day Fun

Earlier this year, in January, Brown gave his 13th State of the State address. The legislators who milled before the speech showcased the ethnic and cultural diversity of California: a white legislator in a cowboy hat, a black legislator in a bow tie. It was Brown who, four decades ago, first brought women and minorities into the political fold. The fruits of that effort were now on happy display.

Brown began his speech with an allusion to his strange political career, then made a joke about how he might use the remnants of his campaign war chest (about $24 million) to push through a referendum abolishing term limits and thereafter run for a fifth term as governor. This was met with laughter, though later in the day California news outlets discussed the plausibility of the proposal, in a sign of how good things under Brown have been.

There was otherwise little occasion for laughter. The speech Brown delivered was short and relentlessly dour, fixated on the downturn sure to come. And whether caused by Chinese currency devaluation or the deflation of Silicon Valley's bubble or maybe some other force malevolent and yet unseen, the downturn was as certain as a traffic jam in Los Angeles. Illinois would not be ready and probably Florida would not be ready, but California would be, with its projected rainy-day fund of $2.23 billion by the end of June 2017.

Never during the State of the State did he explicitly mention the two projects that may define his legacy. The big ideas—water conservation, public transport—were fully subservient to the mundane challenges that, if not addressed, could have the commentariat likening California to Greece once more.

Only toward the very end of his speech did Brown allow for a loftier note, an allusion to the fact that California is not only special but exceptional, a nation unto itself, the end point of Manifest Destiny, the golden place at the end of the land, the Bear Flag Republic in comparison to which all other states are mere cubs.

"We dare to do," he said, "what others only dream of."