As protesters filled the streets in cities across the United States following the killings of black men in Louisiana and Minnesota by police in early July, the normally sleepy Twitter account for Dallas Area Rapid Transit turned grim. "Four DART police officers were shot," it posted before midnight on July 7. "One deceased."

Within hours, the number of Dallas police officers known to have been killed by a sniper during a protest there had grown to five, with nine more wounded. After a two-hour standoff, authorities dispatched a bomb robot to neutralize the suspect, who made his motive clear before he died. "He said he was upset about the recent police shootings," Dallas Police Chief David Brown told reporters on July 8. "The suspect stated he wanted to kill white people, especially white officers." Brown described the attack as "well planned."

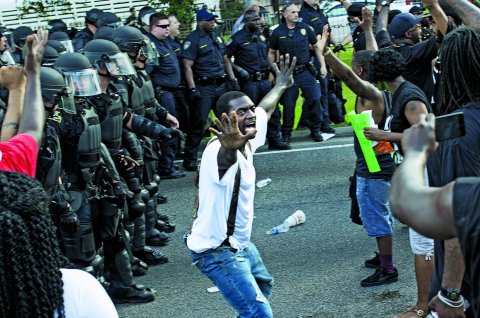

The protests in Dallas that preceded the sniper attack were in response to the fatal shootings of Alton Sterling in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, on July 5, and Philando Castile in Falcon Heights, Minnesota, outside of Minneapolis on July 6. The U.S. Department of Justice has said it is investigating Sterling's death. Those two shootings mobilized the Black Lives Matter movement, which has been speaking out against police violence in the U.S. since the shooting of Trayvon Martin in 2012. Some law enforcement officials complain that the movement paints all cops as villains, and after the Dallas shooting, one Black Lives Matter organizer was quoted as saying, "I understand why it was done."

But most leaders from the black community and protest organizers said the sniper attack is more of the racially charged violence they are fighting. "We mourn the police officers killed beside [peaceful] protesters seeking justice 4 #AltonSterling & #PhilandoCastile in #Dallas," NAACP President and CEO Cornell Brooks wrote on Twitter. And a Twitter account for the Black Lives Matter movement said: "#BlackLivesMatter advocates dignity, justice and freedom. Not murder."

With these killings in Dallas, the number of firearm-related deaths of law enforcement officers is up 44 percent over this time last year, according to the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund, a nonprofit that researches officer fatalities and maintains the national monument to fallen officers in Washington, D.C. The fund reports that 26 officers have been shot and killed in 2016. At this point in 2015, the tally was 18, and for the entire year, 41 officers died in shootings, while 123 were killed overall, including in traffic accidents. (The figures would rise further on July 11 when two bailiffs were fatally shot at a Michigan courthouse as Newsweek went to press.)

"I can't think of anything that compares," says Nick Breul, director of research for the memorial fund and a retired Washington, D.C., police lieutenant, of the Dallas bloodshed. "That certainly is the largest [toll] since 9/11 in terms of a massive casualty incident for law enforcement." (Seventy-two law enforcement officers died during the 9/11 attacks, and dozens more died later from illnesses believed to be related to them, according to the Officer Down Memorial Page, a nonprofit that memorializes fallen officers online.)

Recalling other mass killings of cops, Breul points to 1932, when six police officers were killed while attempting to apprehend a murder suspect and his brother on their family's farm in Missouri. The event became known as known as the Young Brothers Massacre.

More recently, four officers were shot and killed in 2009 at a coffee shop in Parkland, Washington, in what was described as an "execution-style" slaying. The killer died in a confrontation with police days later. His motive remains unclear, though officials said he was likely angry about the time he had spent in prison.

But the Dallas killings are different from those incidents, Breul says, and far more disturbing: "I can't think of anything [else] in law enforcement history when officers in that circumstance, negotiating a parade, managing a public demonstration, are then sort of put into...a shooting gallery and systematically shot."

Dallas police dealt with an ambush shooting a little over a year ago, but no officers died; a man fired upon the police headquarters and left explosives outside the building in June 2015 because he blamed the police for him losing custody of his child and "accus[ing] him of being a terrorist," the police chief said at the time. Officers pursued the suspect, James Boulware, in his van, and he died after law enforcement shot him.

"Ambush shootings," as Breul calls them, are happening increasingly often, numbers show. He says there have been 11 deadly ambush incidents on U.S. law enforcement so far this year, compared with eight in all of 2015. Since the beginning of 2014, 34 officers have been shot and killed in ambushes, says Craig Floyd, president and CEO of the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund, "assassinated because of the uniform that they wear, the job that they do."

"It's a really troubling trend," says Steve Weiss, director of research for the Officer Down Memorial Page and an active cop. Weiss traces the recent uptick back to the December 2014 killing of New York City Police Department officers Wenjian Liu and Rafael Ramos, who were shot with a semi-automatic handgun as they sat in their patrol car.

Dr. Michael Stone, a professor of clinical psychiatry at Columbia University, who published a study last year in the journal Violence and Gender on the murder of 74 law enforcement officers in 2013 and 2014, says such killings are related to growing anti-police sentiment. In his study, he cites one rallying cry of protesters in New York City in late 2014, weeks before Liu and Ramos were killed: "What do we want? Dead cops! When do we want them? Now!"

Floyd agrees: "If we're going to spew anti-cop rhetoric, anti-government rhetoric, then we have to realize there could be consequences of the type we saw in Dallas."

By Stone's count, there was a 39 percent jump in the number of officers—not just police but also corrections and security officers, as well as those from other law enforcement agencies—who were killed between 2013 and 2014. He found that all of the killers in that period were male. (The researcher says he didn't count Amanda Miller, who officials say was involved with her husband in killing officers in Las Vegas in 2014, because he considered the husband the primary killer.) The majority of them had criminal records, and around half died during the altercations. Their ages ranged from 15 to 88, and around half of them were white. Most seemed to have killed on impulse, rather than planning their attacks.

DART named its officer who died as Brent Thompson. The Memorial Fund identified the other victims as Sergeant Michael Smith, Senior Corporal Lorne Ahrens and police officers Michael Krol and Patrick Zamarripa, all of the Dallas Police Department. Police identified the suspected killer as Micah Johnson, 25, believed to be a Dallas-area resident and an Army veteran with no criminal record. At press time, no other primary suspects had been identified.

This latest attack has left many in law enforcement deeply shaken. "If a guy goes and climbs up on a building with a rifle and shoots you from a long distance, there's no training or tactics that can prepare you to defend against that," says Weiss. He expects law enforcement agencies will increase training around "situational awareness," or encouraging officers to keep alert about what's going on around them, and perhaps do a better job of mining social media and web content for threats against police, the way they now look out for postings by extremists.

"Law enforcement is a big family, whether you know an officer or not, whether you're from New York or Texas or Alaska or Hawaii or somewhere in the middle," he adds. "When something like this happens, it affects everybody."

Correction: Citing an academic study, this article previously incorrectly stated that all killers of police in 2013 and 2014 were male. Officials say there was one female perpetrator, who was omitted from the study.