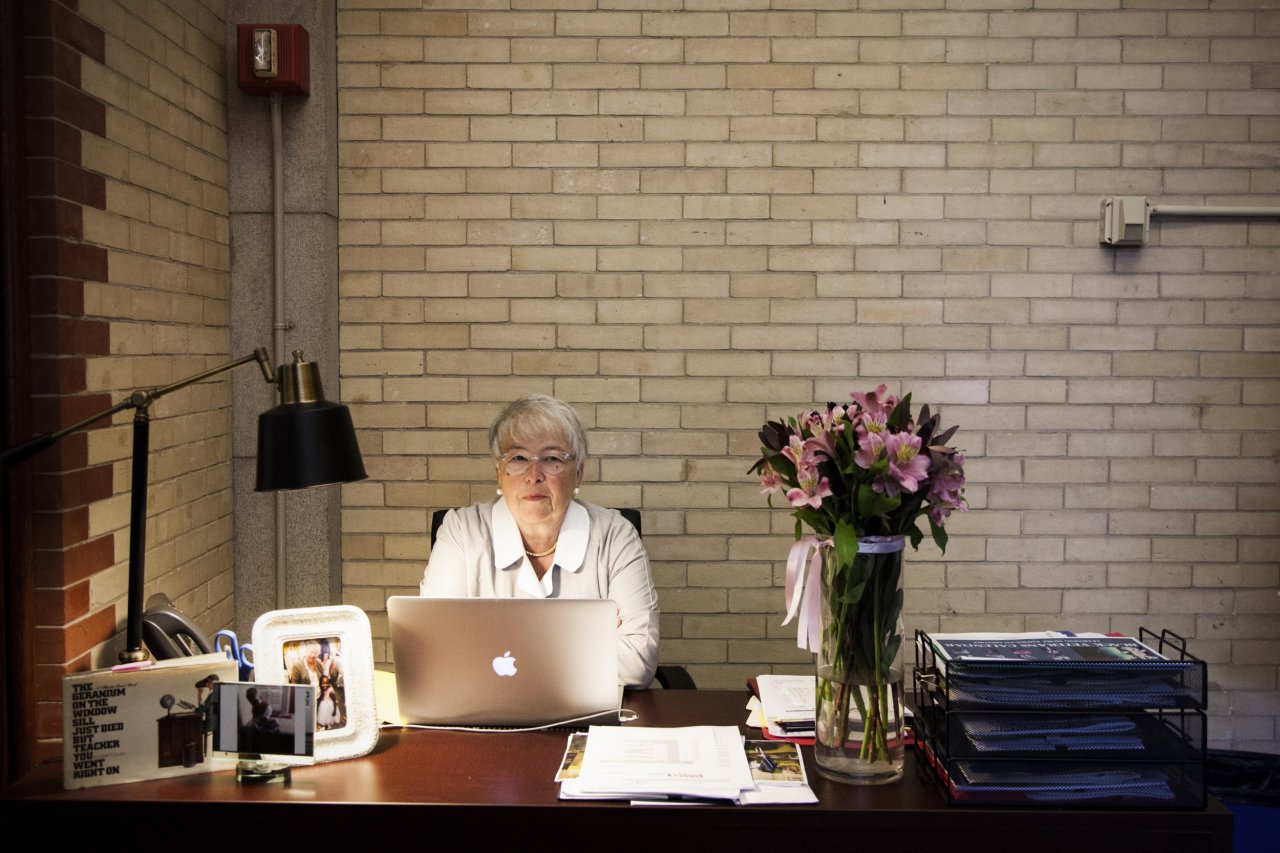

Updated | Everyone wants to think her job is challenging, but Carmen Fariña's is close to impossible: She is the chancellor of New York City's Department of Education. There are 1.1 million students in the five boroughs, which is more than the population of all but nine American cities. There are 1,800 schools in New York; Chicago has 500. Brooklyn Technical High School has more students (5,500) than Princeton does undergraduates (5,200).

The budget for the department Fariña manages is $27.6 billion, which exceeds the gross domestic product of El Salvador. There are 76,000 teachers in New York City, five times as many as in all of Idaho. The quantity of No. 2 pencils used each year is unknown but, most likely, vast enough to fell several forests.

The woman who presides over this pedagogical enormity is a 73-year-old abuela (as The New York Times once called her) from Brooklyn who has been in public education for the entirety of her five-decade-long professional life. Nearly three years ago, Fariña was appointed to the chancellorship by the newly elected mayor, Bill de Blasio, a selection that surprised some who had hoped for a more radical break with the past. De Blasio, after all, is a self-styled progressive who promised "transcendent" change, surrounding himself with youthful advisers minted in the Barack Obama mold. Fariña, meanwhile, was coaxed out of retirement.

De Blasio is now more than halfway through his term, as is Fariña. Neither is especially popular. The mayor is facing several investigations into his fundraising activities, which have left him testy and New Yorkers exasperated; only 42 percent of voters in a July poll approved of the job he is doing. Fariña's approval rating, according to a May poll, is an even-more-dreary 29 percent. Some are wondering if she's doing enough to improve schools, or if she seeks merely to placate the powerful teachers union while stopping the charter school movement. Others believe the school reform movement has been a disaster that only veterans like Fariña can fix.

Since New York is the national bellwether for education reform, Fariña's smallest decisions attract scrutiny. Her biggest often invite fury. Some see her as a defender of teachers, others as the pawn of teachers unions. Is she merely a supporter of big public schools, of the sort that used to anchor a neighborhood, or does she harbor a visceral antipathy toward charter schools, which often swoop in when bigger schools fail? Is she resistant to evaluating teachers and testing students or just suspicious of how easily data can be misunderstood and misused?

These are questions that matter not only to P.S. 75 in the Bronx but also to an elementary school in Tulsa and a high school in Seattle. Much like the New York City Police Department, the New York City Department of Education often instructs the rest of the country in how to do things—and, sometimes, how not to do them.

Fariña's answers to the above questions have been starkly different from those proffered by her predecessor, Joel Klein, a potent symbol of a school reform movement pumped full of money by philanthropic foundations and altruistic hedge-funders. With the blessing of Mayor Michael Bloomberg, Klein embraced teacher evaluations and standardized exams, spurned unions and built charter schools. The efforts of Klein and like-minded reformers were chronicled in the 2010 documentary Waiting for Superman, which demonized traditional public schools as snake pits of union cronyism and chronic failure.

Superman never showed up. Federal programs like No Child Left Behind and Race to the Top left plenty of children well below the summit, while teacher evaluations and standardized tests remain fraught, imperfect measures of teaching and learning. "It's hard to see any good news for reformers," says Diane Ravitch, a New York University professor who is a vociferous supporter of traditional public schools. As evidence, she offers the declining popularity of Teach for America, the alternative certification program frequently viewed as a challenge to union power; the inability of Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg to make an appreciable difference with his $100 million gift to the public schools of Newark, New Jersey; and the shortcomings of Tennessee's Achievement School District, which took over some of that state's most troubled schools.

"The reform team is in decline," Ravitch tells me.

Fariña is a symbol of the traditional team newly in ascent—and not only in New York. Los Angeles has handed its school district to a veteran educator after its disastrous flirtation with reform; Newark also booted its reformer. The return of establishment educators is an acknowledgement that school reform is about more than just giving students iPads or hiring teachers with Ivy League degrees. Maybe the people who know the system best really do know best.

"I consider myself a reformer," Fariña says, "except reforming in a different way." She used the phrase "student achievement" three or four times during our conversation, as if to pacify concerns that the much-touted standards of the previous administration are being scrapped entirely. But she also spoke about arts education and students' emotional well-being. Neither was among Klein's top concerns.

But anxiety about Fariña remains, as her troubling poll numbers indicate: Earlier this year, an op-ed in the conservative New York Post called for her resignation. That came days after the city's principals union head charged that de Blasio and Fariña had "lost their focus on kids."

Paradox alert: The people who know our public school system better than anyone, the ones who suddenly have it back in their hands, were the very ones who allowed American schools to sink into mediocrity, so much so that the most powerful nation in the world does markedly worse than Slovenia in educating its young. The reform movement, after all, would have been unnecessary if previous generations of public educators had done their jobs.

A Messianic Quality

The child of Spanish immigrants, Fariña was born in Brooklyn, her voice touched with the borough's famous accent. After attending New York University, she went to teach in Brooklyn, at P.S. 29, where she was noted for her dedication to students. Later, she became principal at P.S. 6 on the Upper East Side, a difficult assignment because it involved managing the neighborhood's wealthy parents, who tend to bristle at any suggestion that their progeny was not a Nobel laureate in the making. Here, she is said to have honed the style she deploys today, earning her teachers' loyalty but pushing out those she deemed unfit for the job.

In 2000, Mayor Rudolph Giuliani's Board of Education appointed Harold Levy to head the public schools. Shortly thereafter, Fariña came to Levy's attention, probably, he remembers, through parents' favorable word-of-mouth. "P.S. 6 was pretty phenomenal," he tells me. Plucking Fariña from the Upper East Side, Levy appointed her to head Brooklyn's District 15, which includes both parts of brownstone Brooklyn and immigrant areas to the south. Later, after New Yorkers elected Bloomberg mayor and he chose Klein, an antitrust lawyer, to head the school system, Fariña came to work for him as the deputy chancellor for teaching and learning.

Around this time, my fortunes became intertwined Fariña's. In the mid-aughts, I was a young teacher starting out at a middle school in Brooklyn, struggling mostly to get butts into seats and discovering that the poetry of Robert Frost would find little purchase with seventh-graders recently arrived from Kazakhstan and Michoacán.

Like thousands of other young professionals, I became an educator through the New York City Teaching Fellows, a rapid-certification program started by Levy. There was a messianic quality to the Teaching Fellows: Many of us had degrees from expensive private colleges and had not entered teaching as a means into the middle class, the way teachers of Fariña's generation had. Nor were we escaping a military draft. My colleagues left investment banks and production companies, looking for fulfillment, eager for social change. I'm somewhat ashamed to admit that we frequently derided teachers of Fariña's cut, older ethnic whites who'd gone to Brooklyn College, whose voices carried the inflections of the outer boroughs, who were proud of their union membership and spoke knowledgeably of the Yankees bullpen. They were the ones who had broken the schools. We were the ones who were going to fix them.

It did not work out that way. Despite promises that he would be the "education mayor," Bloomberg will far more likely be remembered for greening the city (with both native plantings and foreign cash) than for what he did with the schools. He ended "social promotion," the practice of pushing students into the next grade even if they aren't ready. He closed big failing schools because he believed smaller ones could be more nimble. He pushed for tougher teacher evaluations. He gave schools grades. He welcomed charters. He often said "no" to the United Federation of Teachers (UFT), an enormously powerful voting bloc that always expects City Hall to say "yes."

And after 12 years, what did he have to show for it? Not much. As a Brooklyn College education professor told the Daily News, "They threw everything they had at the problem, but the levels of learning are about the same as they were before. It's amazing how small the improvements are."

By the time de Blasio was elected, Fariña had been out of education for years, having left the Department of Education after what was said to be a contentious tenure there. Known for demanding that his staff adhere to his narrow version of progressivism, de Blasio reportedly had trouble finding a chancellor, especially after his top choice, Stanford professor Linda Darling-Hammond, turned him down. Fariña may have been a good choice, but there was also a feeling that the mayor had settled on her.

"It was always strange to me," says Rick Hess of the American Enterprise Institute, "that a mayor seeking to put a fresh face on radical 21st-century progressivism would've turned the Department of Education over to an apparatchik of the old order."

Shut It Down

To fully grasp the Bloomberg-Klein legacy on education, take the F train to 169th Street in Queens. You are advised to bring a book, since it is a long ride from Manhattan. Exiting the station, you will find yourself in a bustling, low-rise neighborhood that is part suburb and part city. It is populated by African-Americans, East Asians and Latinos. People here are poor, but the feeling on the streets is more of striving than despair.

From the subway station, it's just a short walk to Jamaica High School, a bulky but graceful building that suggests the power and promise of public education. Harvard paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould went there, as did film director Francis Ford Coppola. Jamaica High stands proudly astride a hill, seemingly immune to the forces endlessly remaking the streets below. But that is not the case. In the late 20th century, the school went into decline, as did pretty much every other public institution in New York City. When the rest of the city recovered, Jamaica High didn't. By the late aughts, its graduation rate was only 50 percent.

In 2011, Bloomberg and Klein vowed to shut down Jamaica and 21 other schools, citing poor performance and low enrollment. This was in keeping with their school-busting policy, which held that breaking up a broken big school into several smaller ones was preferable to fixing it. These efforts were bolstered by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, which had spent the past decade promoting this push. In all, Bloomberg closed 157 schools, angering many communities that saw such closures as existential rebukes. Appeals to numbers rarely allayed such concerns.

Another contentious artifact of the Bloomberg-Klein tenure can be glimpsed down the road from Jamaica High School, at 132-55 Ridgedale Street. Here stands the modernist box that used to belong wholly to I.S. 59, a middling middle school. Today, I.S. 59 shares its building with a branch of the Success Academy, a network of high-achieving charter schools founded by Eva Moskowitz, a former member of the City Council.

Like standardized tests and teacher evaluations, charter schools—which take public funds but operate outside some of the rules that bind traditional public schools—are both a state and city matter. But the mayor and his chancellor can set a tone, and the one Bloomberg and Klein set could hardly have been more welcoming. Bloomberg presided over the opening of 166 charter schools, often "co-locating" them in the buildings of traditional public schools, like I.S. 59. This angered some community members, who saw charter schools as usurpers. Moskowitz, a wealthy, white Manhattanite, became a convenient scapegoat for all charter-related complaints. Her sometimes harsh, uncompromising tone did not help.

Among those who sought to curb Moskowitz's ambitions was Fariña, who in 2011 protested the placement of a Success Academy branch in a public school building in Cobble Hill, Brooklyn. It is unlikely that she imagined herself, at the time, ever returning to education, let alone taking the helm of the Education Department. For more than a decade, both City Hall and the Tweed Courthouse, where the central education bureaucracy is based, had been in the grip of uptown Manhattan. Now it was Brooklyn's turn to prove that it could manage the city and its schools.

'Stop Being Ridiculous'

She was going to be nicer: That was the first impression New York City had of its new schools chancellor. "True change happens not through mandates and top-down decision-making but through communication, collaboration and celebrating the successes along the way," Fariña said upon her appointment by de Blasio.

Fariña said sensible things—that she wanted to bring joy back to the classroom and earn the teachers' trust (a generous new contract with the United Federation of Teachers has helped). But while she made clear that the Klein era was over, she failed to outline the goals of the Fariña era, never issuing a promise to students, teachers and parents about what the schools would look like when her term was through. You could have disagreed with Bloomberg and Klein, with their emphasis on data-driven accountability, but you knew exactly what you were disagreeing with. It is harder to say what passes for a Carmen Fariña vision of public education.

"She has not articulated one, that's for sure," says Patrick Sullivan, who until recently sat on the city's Panel for Educational Policy and was also a frequent critic of Klein.

Fariña told me her vision is "equity and excellence." She added that "we can't have lower expectations because of poverty," echoing the reformers' refusal to blame social ills for poor outcomes. "For me, it's all about student achievement," Fariña says—again and again. Whether this was the strength of talking points or conviction, I don't know, but she is clearly eager to rebut critics who see her as more interested in granting concessions to the teachers union than making sure that students are taught well.

I was once a member of a teachers union and have long lamented its moribund conception of the teaching profession. (I was not a fan of the mandatory membership fees extracted from my paycheck either.) The rise of testing and data-driven accountability came about because, for too long, American teaching had been viewed by its own practitioners as a trade, not a profession, a job that rewarded loyalty and longevity and, in several telling ways, was closer to metalworking than medicine. For all its shortcomings, the reform movement reminded the American classroom to fear less the forces that shaped the American boardroom.

De Blasio's signature campaign promise had been universal prekindergarten, and early in her tenure, Fariña appeared to devote considerable time to that program's creation. But a troubling note sounded in the summer of 2014, when she announced her support of "balanced literacy," an English curriculum that emphasizes free reading and writing at the expense of teacher-led instruction. Many educators have concluded that balanced literacy does not work, but a prominent booster of the method happened to be Lucy Calkins, a friend and mentor of Fariña's. You could say (as I did, in a New York Times column) that rigor was forfeited for the sake of loyalty—the kind of thing Klein would have never done.

Several months later, Fariña decided that schools would no longer receive a letter grade, thus putting an end to a signature Bloomberg-Klein innovation. The school grades may have been confusing and leaned too heavily on test scores, but they also sought to answer a question every involved parent has: Does my child attend a good school? In the wake of her announcement, The Wall Street Journal noted that some in the city harbored a "concern about watered-down accountability."

"Revisiting old failed policies and putting a new name on them is not a way to success," one parent said, a charge that has stuck to Fariña—that she is a revanchist disguised as a reformer. These suspicions had newfound evidence when, sometime after the abolition of school grades, she took away the autonomy many school principals enjoyed under Bloomberg, making them answer to regional superintendents.

"Principals need support, but they also need supervision." Fariña said in a talk at Harvard's Graduate School of Education in the spring of 2015 , defending the reintroduction of "strong superintendents." Yet this came across as patronizing, not to mention at odds with the gentler touch Fariña suggested she'd wanted to restore to the department. Informal conversations with past colleagues who have become school leaders suggest that the superintendents micromanage and make their work harder.

Sullivan concedes that Fariña's moves have "blunted the worst of the excessive use of data and testing." The state continues to tweak its approach to teacher evaluations, and while Fariña supports the federal Common Core standards, she is right to see these as more than just test preparation guidelines. At the same time, Sullivan suspects she remains an "old-school principal who wants to control everything."

Her "old-school" tendencies are also responsible, I suspect, for an outsized antipathy to charter schools, which she shares with the mayor. Charters are public schools, and Fariña could have embraced them as a small but critical component of the education system, one that does an admirable job of educating poor kids of color. Instead, she treated them like pariahs. "They're charter schools," she chillingly declared as one fought for space in a public school in Harlem. "They're on their own now."

She and de Blasio were especially adamant about stopping the spread of Success Academy, but Moskowitz had more friends in Albany than they did, and she embarrassed the mayor and his chancellor with a rally that featured thousands of minority children and was addressed by the state's governor, Andrew Cuomo. Lesson apparently learned: Neither rails against the evil of charter schools anymore. At the beginning of the 2015-16 school year, Fariña visited a Bronx charter school and proclaimed, "We have a lot to learn from each other." This counts as progress.

Moskowitz believes City Hall remains "very hostile to charters," citing battles over real estate and accusations that networks like hers shun lower-performing students. Moskowitz represented the Upper East Side on the City Council when Fariña was the principal of P.S. 6 in that neighborhood, and she praises the chancellor for "good instructional instincts." But, Moskowitz told me, "that's very different than being the manager of a big, dysfunctional system."

While the fight over charters was draining, the question of failing schools has been confounding. If you're not going to shut down a school, you have to fix it. De Blasio named 94 troubled institutions in his Renewal Schools initiative; these would be converted into "community schools," social service centers wrapped around a core educational mission, as opposed to just buildings full of classrooms that shut down at dusk (86 remain as of this writing, with eight having been "closed or consolidated," according to a Department of Education spokeswoman). De Blasio's model was Cincinnati, though the implementation of community schools there has not yielded encouraging results. In the last fiscal year, he spent $187.6 million on the project, whose total cost is estimated at $400 million.

Yet nearly two years into the renewal schools program, feel-good rhetoric has given way to murky goals—or, sometimes, seemingly no goals at all. Shutting down schools may have been contentious, but it was decisive. The Renewal Schools plan looks to detractors like a litany of bromides, all carrot and no stick.

Alarms over Renewal Schools have presented Fariña with the biggest crisis of her chancellorship; the 2016-17 school year will be the last full one before the next mayoral election, and hence the administration's final chance to quiet critics who relish any chance to discredit de Blasio and Fariña. This past December, Merryl Tisch, the outgoing head of the state's Board of Regents, alluded to a report in Chalkbeat New York that one school in the Renewal program was given three years to boost student reading by .01, from 2.14 to 2.15 on a 0 to 4 scale. "At some point, everyone has to stop being ridiculous," Tisch said.

Later that month, in what appeared to be a tacit acknowledgement that some schools were beyond saving, the Department of Education decided to shut down three (two of them were in the Renewal program). Fariña may be reluctant to use this strategy, but an MDRC study has found that small schools—the kind Klein opened after shutting down big ones—do a better job of getting poor kids of color into college than their larger counterparts. Many have pointed to that study, released in 2014, as a vindication of Bloomberg and Klein.

As a sign of how widespread displeasure with Renewal Schools was becoming, the program was ripped this past December by The Washington Post, in an editorial titled "Rolling back school reform." It declared the Renewal Schools program was remarkably unambitious and noted that a report from StudentsFirstNY (a nonprofit that advocates for charter schools and school reform) found "rampant grade inflation" plaguing the entire system. The editorial also took issue with de Blasio's antipathy to charter schools. Though Fariña isn't mentioned, it's hard not to see it as a broadside against her.

Then came the striking missive from the head of the city's principals union, an unambiguous sign of mutiny. "Sadly, in the timeworn tradition of the D.O.E., there are so many cooks running around in the kitchen, the chefs don't know what kind of dish they're concocting," said the column, according to The New York Times. "All we have is a recipe for disaster."

When I asked Fariña about Renewal Schools, she argued that social services were necessary, pointing to one school that had more than 150 students living in temporary housing. She also says that she replaced principals at 36 of those schools (seven other schools have gotten new principals since), and though she is loath to close schools, it is a tactic she has already used and, if necessary, will use again.

Meanwhile, she also presides over what has been called the most racially and economically segregated school system in the United States, an all-too-neat microcosm of the "tale of two cities" narrative cleverly deployed by de Blasio to win the mayoral election. But as The New York Times noted last month, "no comprehensive plans have emerged" to integrate the city's schools. That suggests either a lack of vision or an aversion to risk.

A couple of weeks after that dispiriting progress report, the paper said that "academic progress is hard to see" at Renewal Schools, where, "dwindling enrollment and internal conflicts make the prospect that they will succeed seem remote." Public education is an inextricably political affair, and while City Hall can—and has—dismissed the Post as right-wing propaganda, the Times is the paper of record, one that relies not on visceral antipathy but numbers and facts. That makes its recent reporting on New York's public schools all the more damaging to the de Blasio-Fariña narrative of progressivism plus progress.

One of Fariña's top deputies, Josh Wallack, disputes the notion that Fariña is content with the status quo. "This chancellor does not shy away from making the tough calls on personnel," he tells me. In any case, Klein proved that making tough calls—e.g., firing teachers and principals—does not necessarily result in better schools or a more equitable school system.

Also complicating matters is the fact that there isn't a universally accepted definition of a good school. Klein had his; Fariña has hers. When we spoke, she talked about training more nurses and vocational workers, the sort of sensible aspirations that might not make it into a feel-good documentary but may well secure jobs for children in neighborhoods like Jamaica and East Harlem. And she talked with passion about the arts, which have steadily disappeared from classrooms. "For too long, we have graduated students who are silent," she says. "We have graduated students who are not thinkers."

The Way of the Broom

Nobody has ever mistaken Michelle Rhee for an abuela. A graduate of Cornell and Harvard, she was not yet 40 when she was chosen to head the troubled schools of Washington, D.C., in 2007. An acolyte of Klein's, she preached accountability and demanded excellence, firing even the principal of the high-performing school her children attended.

In 2008, Time magazine put Rhee on the cover. "How to Fix America's Schools," the cover line said. The accompanying image showed Rhee grasping a broom. Education reform, the image suggested, was mainly an act of sweeping away the dross. Two years later, she was in Time again, after the mayor who appointed her lost in that city's 2010 Democratic primary. The magazine predicted that Rhee's likely departure would be a "blow to education reform." She resigned shortly thereafter.

Rhee's resignation suggested a shift toward school reform, a weariness with the way of the broom. Bloomberg, reportedly unhappy with Klein, pushed him out of Tweed a month after Rhee's exit in Washington. His replacement was Cathie Black, a Hearst magazine executive with no experience in education. She lasted three months, whereupon the Department of Education was handed over to a middle-of-the-road reformer, Dennis Walcott.

Other districts too have reverted to traditional educators after seeing the grandiose promises of reformers dissolve into air. John Deasy's tenure in Los Angeles was marked by a disastrous attempt to introduce iPads into classrooms, as well as what has been described as an "uneasy relationship with the teachers union." He has been replaced by Michelle King, a veteran of the Fariña model. King, like Fariña, will have to confront the expansion of charter schools, which is even more aggressive in Los Angeles than it has been in New York.

Cami Anderson was supposed to fix Newark's schools; she left last year, to the joy of many residents. San Francisco has doubled down on Richard Carranza, a longtime educator, instead of seeking a Michelle Rhee of its own (as this article was heading to press, Carranza announced that he was heading to Houston, where he will lead one of the largest school districts in the country).

Hess, the American Enterprise Institute scholar, says it is too simplistic to say the school reform movement is over. He divides reformers into two camps: engineers and gardeners. The engineers are those like Klein and Rhee who see improvement as "a matter of pulling this lever and imposing that requirement": more frequent tests, tougher teacher evaluations. This drive for reform has "stalled out," he argues. But there are also the gardeners, who harbor the "conviction that all policy can really do is foster the conditions under which good things are more likely to happen." The gardeners, he suggests, continue to thrive.

I spoke to Randi Weingarten, who was my union president when I was a teacher. She left New York and the UFT for Washington, to head the American Federation of Teachers, and was treated especially roughly in Waiting for Superman, which portrayed her as a craven labor boss with no concern for the children her union members were supposed to be educating. That harsh characterization seems, at least to me, far more fitting for her UFT successor, Michael Mulgrew, than Weingarten, who radiates a fundamental dignity.

Weingarten told me reformers like Anderson, Klein and Rhee "created tremendous turmoil and tension…. Their view was the system itself was the problem." Like Hess, she sees reform as a nuanced business, and it hurts her that only those with grandiose visions of accountability and Big Data earn the coveted "reformer" label. She thinks that "two decades of test-and-sanction" are coming to an end and that chancellors like Fariña can restore confidence in teachers while also making sure they do their jobs.

As for Fariña, her job is safe as the 2016-17 school year begins, even as many other high-profile de Blasio appointments (police chief Bill Bratton, legal counsel Maya Wiley) depart what has been called a chaotic and micromanaged City Hall. Austin Finan, a spokesman for the mayor, told me de Blasio stands behind her "100 percent. When you change the status quo, you're going to have critics along the way," he says. Noting rising graduation rates and falling dropout rates in New York City public schools, Finan adds that "under Chancellor Fariña, our schools are moving in the right direction." State test results released earlier this month showed New York City's public school students making gains in both math and reading, bolstering the case for Fariña's leadership. Many of the Renewal schools saw their scores rise, too, and while that may not silence critics, it does seem to validate the holistic approach touted by de Blasio and Fariña.

Klein's supporters were no less cheerleaders than Fariña's, even though his path forward was nothing like the one charted by her. Everyone wants to return to that golden age when the American school was the crucible of upward mobility, when public education was a matter of national pride and international envy. Only we all have different maps, with different cardinal points. One day, charter schools are the north star; the next day, it is language immersion programs. We need more standardized tests but also more art classes. Respect teachers but also measure their work relentlessly.

This state of affairs is unfortunate but not surprising. We are not a small, monocultural nation like South Korea, or an autocracy like Russia where a history textbook might fall victim to Kremlin diktat. In America, school reform will always be a Hegelian contest between clashing visions, frequently maddening, infrequently productive. It is the only way we know.

Editor's Note: This article has been updated with the correct location of Fariña's place of birth, Brooklyn, New York, and the length of her career, as well as with more accurate details of Harold Levy's appointment.