Once upon a time, Bill Clinton thought he had rid the world of worry about the nuclear dreams of the cruel dictator of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea, aka North Korea. The Agreed Framework was signed in 1994: Pyongyang promised to shelve its pursuit of a nuclear weapon in return for energy assistance—in the form of a light water nuclear reactor—from the United States, Japan and South Korea.

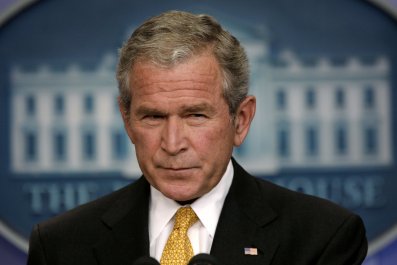

That deal died during the administration of Clinton's successor, George W. Bush, when the U.S. confronted the North about its secret effort to enrich uranium in pursuit of the bomb (the program covered by the Agreed Framework was for the North's pursuit of a plutonium-based weapon). Ever since, Pyongyang and the outside world have been trapped in an endless loop: North Korea, slowly increasing its small nuclear arsenal, conducts another nuclear test; an outraged world passes United Nations resolutions to increase sanctions on Pyongyang—sanctions meant to inflict sufficient economic pain to bring Kim Jong Un, the current dictator, to heel. After the passage of some time, Kim tests another bomb, just as he did on September 9.

This has become so routine you've probably forgotten that this precise sequence of events has already occurred this year. In January, the North tested a nuke—its fourth such test—and after two months of talks the Security Council passed Resolution 2270. Still, skeptics warned, in order for Resolution 2270 to curtail North Korea's persistent violations, all U.N. members need to enforce the sanctions. And that includes the People's Republic of China, Pyongyang's lone ally. It's the only country in the world that can make or break the North Korean economy.

There are only two questions that really matter here: Is Kim crazy enough to use one of his nukes in an attack on Japan, South Korea or the United States? The received wisdom is, no, he is not that crazy, because such an attack would almost certainly result in the obliteration of North Korea. Second, then, is the question of China. Does Beijing want to put so much pressure on the regime that it might destabilize the North, or does Pyongyang's value as a strategic buffer in northeast Asia—a firewall against the U.S.–South Korea alliance—mean that Kim can basically do whatever he wants with his nukes, so long as he doesn't use them.

Beijing is Pyongyang's economic lifeline—roughly 70 percent of North Korea's total trade is with Beijing—and its main supplier of energy and food. If Beijing wanted to cut off Pyongyang, even more lights in the North would go off—and stay off. There have been moments when Beijing has wielded its clout: Early in 2003, for example, Pyongyang test-fired a missile in contravention of U.N. resolutions, and China stopped shipping oil to the North for three days. In 2013, South Korean Foreign Minister Yun Byung Se said, "China appears to have increasingly viewed the North's military adventurism as a strategic liability, instead of a strategic asset." The following year, Chinese President Xi Jinping appeared to snub Pyongyang by visiting Seoul before Pyongyang—the first time a Chinese leader had done so. For a brief time, the U.S. and its key East Asian allies, South Korea and Japan, thought the campaign of "strategic patience" with the North might be working, given Beijing's apparently mounting irritation.

That moment passed, and now, just months after detonating its fourth nuke and withstanding the latest round of U.N. sanctions (and alleged Chinese anger), the North has tested an even bigger bomb. The endless loop plays on: President Barack Obama left meetings in the Laotian capital of Vientiane stating the obvious—that he needed more help from Beijing to rein in Kim.

But has anything changed in the past few months that would alter China's strategic calculus? Beijing enforced some tougher sanctions after the March nuclear test, but none that would meet the "bone-numbing" standard, in Seoul's words, necessary to get Kim's attention. Beijing knows the North's nuclear program is more shield than spear: It is the guarantor of the Kim dynasty's survival. No one will pre-emptively attack the regime, since it has nukes. China also believes Obama's "pivot" to Asia is a plan to encircle China with U.S. allies nervous about Beijing's growing military clout in the region. Beijing was angered by Seoul's willingness to adopt the U.S.'s Terminal High-Altitude Area Defense system. Though it will be deployed as a hedge against missiles from the North, Seoul's agreement with Washington to deploy was seen in Beijing as a snub, since China has publicly warned South Korea against THAAD.

As long as Beijing does not believe the North would use its nukes against its lone ally, then Pyongyang's test of its fifth, sixth, seventh or eighth nuke won't change the calculus. Beijing wants stability on the Korean peninsula above all else. So the cycle is likely to continue: China will agree to punish Pyongyang a little bit harder each time but not enough to truly imperil the regime.

That leaves Washington with a problem. Obama will attend his final U.N. General Assembly meeting this month, and once again tougher sanctions on North Korea are on the agenda. The Security Council members will probably agree on something, but will Washington adopt its own tougher sanctions against governments and companies that trade with North Korea—or even enforce existing sanctions that could hit Chinese entities doing business with Pyongyang?

It's likely that the Obama administration, on its way out the door, will not take such strong measures. Obama said recently he views climate change as the most consequential issue he has had to deal with, and China, the world's largest emitter of carbon dioxide, is the key to doing something about it. Seriously upsetting Beijing is not something this president will do. What a President Hillary Clinton or Donald Trump would do is anybody's guess (though Trump, in his limitless confidence in his ability to negotiate "good deals," has said he would talk with the North Korean dictator).

Forget about it, Donald. The depressing bottom line is that putting off the issue, while believing that Kim won't hurt anybody with his nukes, remains the only option that doesn't risk a possibly calamitous confrontation with the North—and Beijing. Expect whoever is in the White House next to realize that.