Before a University of Miami–Notre Dame football game in the late 1980s, a team chaplain for the Hurricanes dismissed the notion that the Catholics from South Bend, Indiana, had the Almighty on their side. "God doesn't care who wins football games," the cleric huffed.

When Lou Holtz, the Fighting Irish coach at the time, heard that, he said, "I don't think God cares who wins either," adding with a sly grin, "but his mother does."

How did Mother Mary, the most renowned female figure in history, a paragon of virtue and pacifism, become so inextricably linked to the violent game of American football? How is it that on almost any autumn weekend her name is invoked not only in prayer but by broadcasters? How did the most spectacular play in America's most popular sport come to be known as the Hail Mary pass, and why do we love it so? "The greatest stories have the largest arcs," says ESPN analyst Brock Huard, a former NFL quarterback. "That's what makes the Hail Mary special. In an instant, it flips the entire story upside down."

Agony to ecstasy. Misery to redemption. Flutie to Phelan. The Hail Mary pass redeems lost souls while tormenting, if not sinners, then defenses who rush three players while dropping eight. For those who feel its awful sting, the Hail Mary is sport's answer to inexorable fate: knowing what is coming yet being powerless to stop it.

Holy Mosh Pit!

On a recent Saturday, in the gloaming of Athens, Georgia, the University of Georgia Bulldogs trailed the Volunteers of Tennessee 28-24 with 19 seconds remaining. Georgia quarterback Jacob Eason took the snap near midfield, drifted right in the pocket and fired a 47-yard pass to Riley Ridley, who caught it in stride along the left sideline as he crossed into the end zone. That was not a Hail Mary. "No, not at all," says Huard. "Eason knew exactly who his intended receiver was, and he hit him in stride."

One play later, following a kickoff and two penalties on the Bulldogs, Eason's counterpart for the Vols, Josh Dobbs, took the snap with 4 seconds and unleashed a 43-yard invocation toward the end zone. "Dobbs heaves it," intoned CBS announcer Verne Lundquist. "They're bunched up in the end zone.… It's tipped up [it wasn't, but Uncle Verne is 76 years old, and you try calling a Hail Mary pass on the fly].… It's caught! It is caught! Jauan Jennings! Jauan Jennings!" Now that was a Hail Mary.

The Hail Mary, for those of you familiar only with the prayer ("full of grace/The lord is with thee.…"), is a pass thrown in desperation at the end of a football game. While the term has come to be associated with any unlikely game-winning toss as the clock expires, the genuine Hail Mary has these defining features: (1) The pass must be thrown from at least 40 yards outside the end zone; (2) the team attempting the pass must be trailing; (3) the game must be in its waning seconds—ideally, the clock expires during the play; and (4) the pass must be directed not so much to a particular receiver as to an area near the goal line.

"I like to think of it as a mosh pit, the area where the ball is thrown," says Huard, a Seattle native who played at the University of Washington in the 1990s, in the age of grunge. "There have to be players from both teams scraping and clawing one another to get in position to catch the ball."

A mosh pit is a fine description, but the Hail Mary more closely resembles a bride tossing her wedding bouquet over her shoulder to a klatch of distaff guests. There is that sense of the blind heave, the pregnant anxiety as the projectile traces its parabola, the scrum as hopefuls jostle for position, the euphoria of having snared the prize and the anguish of having not. All that's missing is Brent Musburger bellowing, "I don't believe it!"

Among the singular plays in sport, the Hail Mary has no equal. The walk-off home run is close, but that situation produces a wider range of outcomes than what "Casey at the Bat" would have you believe. Sure, the batter may strike out or clout a game-winning home run, but he also might draw a base on balls, extending the ultimate outcome for at least one more batter. The Hail Mary is an all-or-nothing gambit in which gravity ensures that a resolution is nigh. It is putting all your money on red or black at the roulette table, as opposed to splitting it across four numbers.

"That's what makes it so incredible, the suddenness and the finality of it," says Huard. "And I think it's different for players and coaches. For players, the excitement of being on the winning side of the Hail Mary probably far outweighs the feeling of being a victim of it. But for coaches? Losing on a Hail Mary is probably something that will be with them until the day they die."

Full of Grace Notes

There are more Hail Marys on YouTube than there are beads on a rosary: the Miracle at Michigan, Kordell Stewart's 64-yard heave to Colorado teammate Michael Westbrook that shocked the Wolverines in 1994; the Prayer at Jordan-Hare, Auburn's 73-yard, fourth-down Lazarus act against Georgia (the Bulldogs are sorely in need of some good karma) three years ago. In the NFL, you can point to Aaron Rodgers's two Hail Mary tosses last season, of 61 and 41 yards; or to the Fail Mary of 2012 in Seattle, in which players from both teams appeared to catch the football.

Time and space limit a closer examination of them all, but there is one man we know of, ESPN's Musburger, who was present at the two most famous Hail Mary plays in the game's history: the Dallas Cowboys' answered prayer in the 1975 NFC playoff game against the Minnesota Vikings in Bloomington, Minnesota, and Hail Flutie in Miami nine years later. "What I remember about the [Roger] Staubach to [Drew] Pearson pass is that it looked like Pearson pushed off the defender," says Musburger, who as a CBS pregame host was standing across the field but at the same end zone. "I also remember that it was incredibly cold."

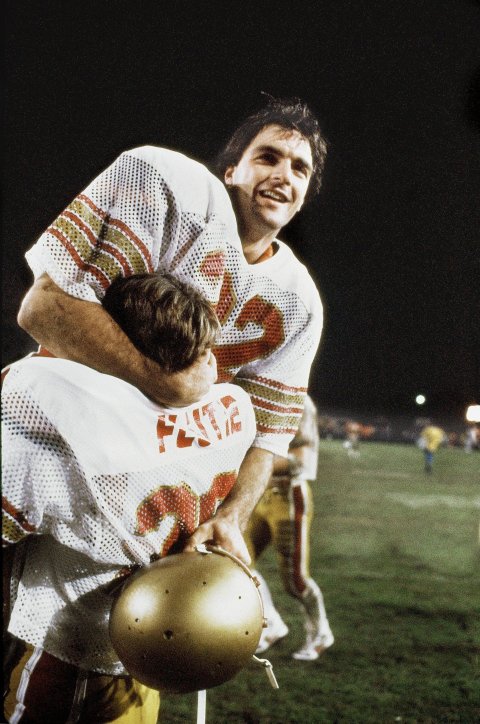

Musburger, 77, has more vivid memories of the game he called between Boston College and Miami for CBS on the Friday after Thanksgiving in 1984. The Hurricanes led 45-41 with seconds remaining. The Eagles, led by diminutive Heisman Trophy candidate Doug Flutie at quarterback, snapped the ball from the Miami 48. "Flutie was flushed from the pocket," recalls Musburger. "As the ball sailed through the air [it would travel 65 yards], the only thing I could see was that a BC player had caught the football. But I didn't know who."

Fortunately for Musburger, a Boston College alumnus who was also a CBS executive was in the production truck. He strode to the mic connected to Musburger's earpiece and said, "Phelan. Gerard Phelan."

Musburger, showing the same blind faith that Flutie had displayed just moments earlier, repeated the name to his slack-jawed television audience. "Years later, Flutie told me that he had no idea who caught the ball either," says Musburger. "He asked his center as they were walking off the field, and he replied, 'Doug, it was your roommate.'"

Jude Not

The Hail Mary, like an anvil falling from the sky toward Wile E. Coyote's head, has an inexorable and painful nature to it. What makes it maddening for defenses is that they know exactly what is coming and yet are sometimes powerless to stop it (according to ESPN Stats & Info, roughly 10 percent of the Hail Mary passes attempted over the past five years have worked; as a metric for success, that is low, but as one for prayers answered, you could do a lot worse).

What are the most surefire ways to be taken down by a Hail Mary pass? First, only rush three down linemen. Second, put a committee of defenders near the end zone, all of whom assume their teammate is going to be the one to knock down that missile from above. Against Tennessee, Georgia coach Kirby Smart put the Bulldogs' tallest player, 6-foot-6 linebacker Lorenzo Carter, in the end zone for the explicit purpose of knocking the ball down, but Carter wound up being boxed out by two of his teammates as the Vols' Jennings secured the trophy from out of the sky. "Everybody on the field executed their job," Smart said with dismay, a remark that may remind you of what former USC coach John McKay said when asked what he thought of his team's execution after a loss. Quipped McKay, "I'm in favor of it."

The Hail Mary is not only an anomaly; it is a misnomer. After all, Saint Jude is the patron saint of lost causes, and it is to him that Catholics often pray when things look bleak. If there were ever a saint whose name you'd want to invoke in hopes of completing a desperation pass—besides Drew Brees—you might think it would be Jude. How about a "Prayer to St. Jude," or even, to secularize it, "Hey, Jude?" But no, the Hail Mary has slipped into common parlance. Why?

The answer may be found at a certain Midwestern, football-obsessed university that is named in her honor. Notre Dame, translated from French, is "Our Lady."

On November 24, 1934, Army and Notre Dame were playing in front of 80,000 fans at Yankee Stadium. With the score 6-6 in the fourth quarter and Notre Dame at its own 48-yard line, Irish quarterback Andy Pilney completed a 27-yard pass, in heavy traffic, to receiver Dan Hanley. On the next play, the two hooked up for the game-winning 25-yard touchdown. Writing for the Daily News, columnist Paul Gallico said of the former of the two completions, "This pass carried on it several Hail Marys, not to mention the special blessings of Rome. It was fired with devout faith."

Six days later, The Scholastic, the school's weekly student publication, vilified Gallico for what it considered his prejudicial commentary (and you thought hypersensitive college students were a 21st-century phenomenon). "[Gallico] has no right…to bring religious prejudice into an alleged account of an athletic contest marked by unusually fine sportsmanship," the weekly sniffed.

In the same issue, in its own report of the contest, The Scholastic described the play thusly: "With the impossible staring him in the face and with the Army's pass defense tighter than a Scotchman's purse on the first of the month, Andy [Pilney] passed. Dan Hanley leaped high in the air and snagged the ball out of the hands of two surrounding Cadets, being downed immediately on the 25-yard line." One scribe's prejudice is another's snark.

Although Gallico's is the first written reference to "his mother" in relation to football, for years former Notre Dame football player and coach Elmer Layden told a story on the banquet circuit, claiming that the initial invocation occurred in 1922. During a game at Georgia Tech, with the Irish trailing 3-0 in the second half, an offensive lineman who happened to be Presbyterian supposedly suggested in the huddle that the team say a Hail Mary. The play went for a touchdown.

Later, facing a fourth down, the same player made the same suggestion, with the same result. The Irish won 13-3 and, according to Layden's punchline, that player told his teammates, "That Hail Mary is the best play we've got."

The tale is at best apocryphal, but it bears repeating for this reason: The player in question was named Noble Kizer. Notre Dame's quarterback this season is named DeShone Kizer. And while the two are not related, it may interest you to know that the school of Our Lady has never completed a genuine, game-ending Hail Mary.