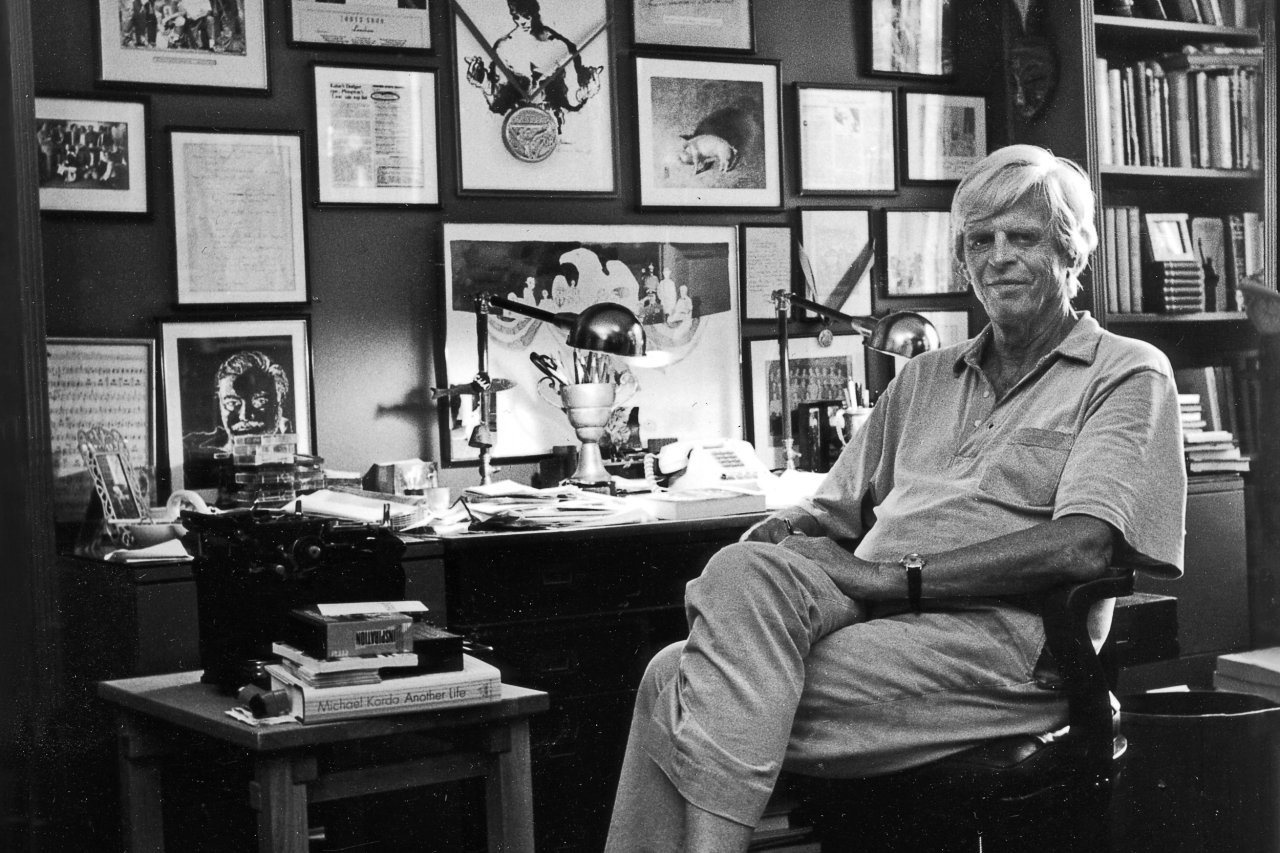

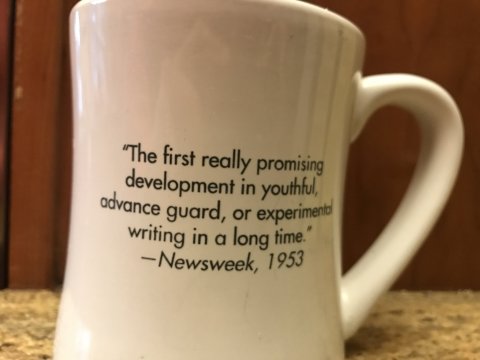

Like most people, I have a large and largely meaningless collection of coffee mugs, their provenance for the most part unknown. Yet one stands out, even if its capacity to deliver hot, caffeine-laced water is no greater than that of its ceramic peers. The mug is emblazoned with the logo of The Paris Review, the literary magazine founded by George Plimpton in 1953, and an approving quote from Newsweek: "The first really promising development in youthful, advance guard, or experimental writing in a long time."

I'd spotted the mug at a Paris Review party in Manhattan a couple of years ago, in the kitchenette of the West Chelsea loft where the magazine moved after vacating the East 72nd Street townhouse where Plimpton ran the publication until his 2003 death. The day after the party, I sent Lorin Stein, the editor of the Review since 2010, a note; he, in turn, kindly sent me the surprising, not to mention useful, memento of our respective publications' long-ago bond.

Sometime after that, I went hunting for the 1953 Newsweek issue that covered the birth of The Paris Review in the intellectual hothouse that was postwar New York City. Newsweek was harder to navigate back then than it is today, and I ended up spending several hours learning about a year that surely deserves a book of its own, as much as 1968 or 1914: the discovery of DNA, the death of Soviet despot Josef Stalin, the Mau Mau rebellion in Kenya, the polio vaccine pioneered by Jonas Salk, the ascension of Elizabeth II to the British throne, the execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg—all of it studded with advertisements for cigarettes and long-defunct airlines.

RELATED: A new Chumley's for a new Manhattan

As for the Paris Review quote, I never found it, but its mere existence (assuming Plimpton didn't make it up, which, if you know anything about him, is a not all that remote possibility) has always struck me as poignant, even a little heroic. Despite the turbulence of that time, Newsweek found time to cover the creation of a new magazine, an event that would today occasion little more than a few congratulatory tweets. Newsweek was not especially prescient or highbrow; rather, the nation as a whole was more cultured and took the arts more seriously, so that a new literary magazine was indeed big news worthy of coverage in a newsweekly. Ernest Hemingway and John Steinbeck were best-selling authors. Duke Ellington issued his album Piano Reflections; Arthur Miller's The Crucible premiered on Broadway. It's not that we had a high culture; we had culture. And the wording of that brief Newsweek quote—"advance guard," especially—suggested that the culture was fighting for something profoundly important and just as profoundly American.

Preserving Cultural History

Call me a nostalgist, but I miss those days, at least in that narrow sense (don't bother pointing out that there were many awful things about the 1950s; that is obvious, and true about every other epoch of human history, except maybe for those years in which the Mets won it all). That popular culture, namely television and the internet, has replaced actual culture, namely literature and the arts, seems a point well beyond argument, what with revered This American Life host Ira Glass declaring on Twitter—where else?—that "Shakespeare sucks." It's telling that since the 1990s, "culture wars" have not had anything to do with intellectual debate but, rather, are about the right-wing assault on the very notion of culture: trying to defund the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) for sponsoring transgressive work by the likes of Robert Mapplethorpe; banning books by Toni Morrison and Khaled Hosseini, among many others who run afoul of the right's faux-Christian ideology; railing against filmic representations of gays and lesbians; deriding any publication that tries for nuance and demands rigorous thought as yet another example of coastal snobbery. This conservative crusade has culminated in the election of the proud vulgarian Donald Trump, who frequently hints at a kind of joyful illiteracy.

A few days after the election, The Paris Review made news in the literary world by announcing it had digitized the entirety of its archive, a considerable achievement for a publication whose every issue is essentially a book-length anthology. This, along with a sleekly redesigned website, was evidence that, as New York Times book critic Dwight Garner wrote in December, the Review has been "on a hot streak."

Diving into the digital archive, as I did, is a bracing reminder of the artist's duty in times of national crisis—and there were very few times in the Review's first two decades when the nation wasn't in crisis, between the John F. Kennedy assassination, the civil rights movement, Vietnam and Watergate. Resistance then wasn't retweeted; it was rendered in poetry and prose.

Thus you have William Styron publishing an excerpt from his hotly debated The Confessions of Nat Turner, a novel of racial violence for a nation fighting over race anew; Edward Hoagland's short story "The Witness" (1967), written from the perspective of a young man in New York "full of minority sympathy"; the poet Ted Berrigan, writing in 1968, in the bleakest days of Vietnam: "The War goes on & / war is Shit"; David Lehman admitting in 1995 that he'd never liked the towers of the World Trade Center, but after they were bombed in 1993, he suddenly came to appreciate "the way the tops/of the towers dissolve into white skies/in the east when you cross the Hudson"; the violent silhouettes of slavery life by artist Kara Walker, published in the Review in 1999, seven years before her career-making solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art.

Of particular pleasure are the "notices" by Plimpton that open many issues of the Review. Never a firebrand, he managed to convey his cultural and political convictions without hurling the kinds of rhetorical bombs that characterize so much discourse today. In 1974, Plimpton announced in his editor's letter that he was joining a campaign with bookseller Waldenbooks to get Americans to buy more books. "Jonathan Swift spoke of books as being 'children of the brain,' but the American home has become a nursery without children," he wrote.

Nineteen years later, as the Review turned 40, Plimpton railed against the loss of an annual $1,000 grant from the NEA. "It is despairing that this country—or at least its Congress—does not consider its artists worthy of the same kind of support given by, say, France, which knows that its cultural heritage is an entity to be supported to the fullest," he wrote. He continued on this strain in the next issue, noting that "the city of Munich spends more on literature than the U.S. So does the Basque Ministry of Culture. The Canadian Province of Ontario spends twice as much." Things haven't gotten much better, with a 2014 analysis concluding that the United States spends 40 times less on the arts than Germany. Given the lowbrow predilections of the incoming president, we may soon find ourselves on par with Papua New Guinea.

Some have accused the Review of being too political—and not in the service of the liberal cultural establishment with which it is usually associated. The recent publication of Joel Whitney's Finks: How the CIA Tricked the World's Best Writers resurrects the claim that the Review's founders, in particular Plimpton and Peter Matthiessen, were working with that agency. In a Salon essay from 2012 on which his book is based, Whitney writes that The Paris Review was supported, in part, with regular funding from the CIA-backed Congress for Cultural Freedom. The magazine thus became, in Whitney's complex tale, part of the Company's "vast quest to beat the Soviets in cultural achievement and showcase American writing to influential European audiences and intellectuals." It made things only easier that the two institutions drew heavily on the refined men of the Ivy League, who could recite Chaucer or charm a Bulgarian diplomat over cocktails.

The 'Beginning of Who Knows'

Speaking of which: Earlier this winter, I joined Stein at the offices of The Paris Review as he mixed brain-cleansingly strong Manhattans and spoke about literature in the age of Trump. The morning after the election, he'd gathered his aghast staff to chart a path forward. Plainly, that would include at least some material on the nation's new president. Since the election, the Review's website has published a cri de coeur by its Southern editor, John Jeremiah Sullivan, in which he professed a "bone-and-mother love" for this country and a fear for its future; Mike Powell filed a sensitive dispatch from Tucson, in which he profiled Raul, a native of Tijuana, Mexico, living in Arizona on an expired green card and playing in a band called Rock en Español. "Now is the beginning of who knows," Raul tells Powell, who'd spent election night tripping on acid.

As we drank and spoke throughout the frigid evening, digital editor Dan Piepenbring lingered in the office. He told me that he'd been inundated with Trump-related submissions since the election and was trying to find how to strike the balance between content that took on Trump and content that ignored him. The conundrum reminded me of a famous George Orwell saying: "All art is propaganda; on the other hand, not all propaganda is art." An editor who can't discern between the two is a flack with a red pen.

Stein says that web traffic at the Paris Review is up 20 percent since the full online archive was launched on November 23. Just as encouraging, there have been 3,000 new print subscribers—myself, for the first time, among them. "The Review has more readers today than ever before," he wrote in a recent fundraising letter. "It stands for a community bound together, not by an echo chamber, but by a shared sense of tradition and vitality." As for the suggestion, being promulgated by Whitney, that the Review's mission is somehow tainted by a CIA affiliation, Stein dismisses the findings of Finks as "unconvincing," the evidence thin and circumstantial.

We argued about whether all art was political—and how political art should be. The argument continued later, over email. "I was impressed and surprised by how consistently the magazine avoided politics from the top," Stein wrote to me, "even after Plimpton campaigned for Robert Kennedy, and wrested the gun out of Sirhan Sirhan's hand—while always, at the same time, being open to politics in fiction and poetry. I suspect the editors wouldn't have called it 'political' to publish gay love poems or a poem about sexual harassment, or a story about dealing with the draft. But we would, looking back."

I was playing with my toddler son on the floor the other day when my eyes alighted on a low bookshelf I normally didn't browse. Squeezed between a couple of obscure tomes was a Paris Review issue from 1962. How it came into my possession, I have no idea. It was the winter-spring issue: the beginning of the U.S. embargo against Cuba, Jacqueline Kennedy's famous TV tour of the White House, the battle for Algerian independence, the hanging of Nazi henchman Adolf Eichmann in Israel.

Back then, the Review struck the same tone as it does today, humanistic and inquisitive, but understated where another publication might be infuriated. The first item in the magazine is a short story, "The Revolutionary," by the Italian writer Mauro Senesi, about a radicalized young man named Adias: "Once in a lifetime, he said, while the fury turned his eyes wild again, the time is ripe, and a man can be as hateful as he wants."

A poem by Robert Bly captures the mood of 2017 as much as of 1962:

If we are truly free and live in a free country,

When shall I be without this heaviness of mind?

There is also an interview with the novelist Mary McCarthy, who had a long history of political activism. Asked by the interviewer about her present-day convictions, McCarthy calls herself a "libertarian socialist," whatever that means, but also expresses a pessimism about the political scene. She then voices a sentiment increasingly popular today, what with the rise of demagoguery, and the ocean levels also rising, and everyone building nukes, and Adam Sandler still finding work, somehow. "It really seems to me sometimes," McCarthy says, "that the only hope is Space."