Through the clear running water, the goose bumps on her skin are just visible; her white dress floats above the riverbed. The scene is peaceful—but her story is not. One year before this photograph was taken, this woman was raped at gunpoint by a man she thought wanted to help her. Marie—not her real name—was a student looking for a job in Port-au-Prince, Haiti's capital. "I met this guy on the street," Marie says. "We started to chat. He said that one of his friends was looking for someone like me. He said that he needed to go to his place. When we got there, he pulled out his gun. This is when it happened."

Marie's experience is all too common in Haiti. During the military's rule from 1991 to 1994, it used rape as a weapon to intimidate and punish women, and after a coup in 2004, thousands of women and children were sexually assaulted, including more than a hundred victims who alleged assault by U.N. peacekeepers, according to recent investigations. Women's organizations have pushed for reforms to the penal code to improve legislation protecting women, though government inaction and political instability have stalled the attempts. Rape became a serious crime only in 2005, after a group of women pushed for a change in the law. (Previously, a rapist could pay off or marry his victim.)

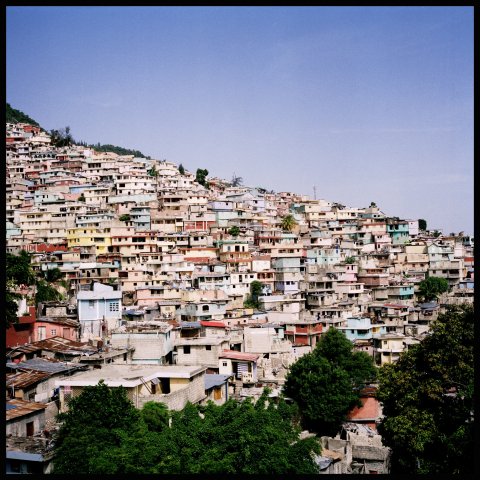

Though rape is a perennial problem in Haiti because of poverty, instability and attitudes toward women, reports of sexual violence surged after the 2010 earthquake that destroyed much of Port-au-Prince and left 1.5 million people homeless. Isolated bathrooms, poor lighting and a lack of safe housing made women vulnerable to attacks in the city's makeshift camps, where, in 2012, residents reported sexual assault at a rate 20 times higher than Haitians living elsewhere, according to The New York Times. Doctors Without Borders reported that the earthquake destroyed 60 percent of existing medical facilities, including those for victims of sexual violence. Meanwhile, desperation for food and water caused the rise of what one women's organization called "survival sex"—women and girls having to sell their bodies for food. Years after the earthquake, Human Rights Watch estimates that 61,000 displaced people still live in the camps.

French photographer Benedicte Kurzen spent three weeks last summer with women treated at a sexual health clinic founded in May 2015 by Doctors Without Borders, widely known by its French name, Médecins Sans Frontieres. Usually based in Nigeria, Kurzen had visited camps of people displaced by the Nigerian militant group Boko Haram, hoping to tell the story of the women who had been raped, to "help them gain self-confidence again." But in Nigeria, she found the trauma was so recent that the women needed psychological and medical attention—and photographing them did not seem appropriate. When MSF invited her to Haiti to photograph women who had received counseling in their clinic for months before she arrived, she found subjects for whom the experience was less raw.

Read more: After 13 years and several scandals, U.N. peacekeepers are leaving Haiti

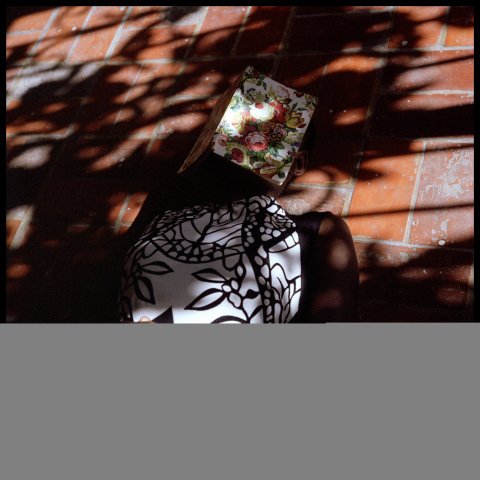

Though Kurzen was there to highlight the issue of sexual violence and the clinic's work, she also wanted the photos to bring joy to the women in them. Each woman decided how she preferred to be photographed, each expressing her own identity as a woman, not a rape victim. Kurzen's subjects hoped that by being part of the project to raise awareness of the clinic, other women could get the same help they did.

"I knew I wanted to focus on the absolute resilience of these women—on them being not victims, but survivors," Kurzen says. "Despite what happened to them, you can still have a sense of their beauty."

Kurzen spent time with each subject to build a relationship. Not all discussions panned out, particularly in the case of younger subjects. "Some of the minors were so vulnerable. We spoke to a mother of one girl who really wanted to be part of the project. She was much more uncomfortable with the picture than the daughter was; there were anger issues. She thought [the rape] was her daughter's fault." In the end, Kurzen and the team referred the mother for counseling. "We helped without taking the picture."

The earthquake had made women in Haiti particularly vulnerable, but Kurzen also wanted to photograph women outside the camps who were affected by sexual harassment and assault. "These were completely day-to-day situations," Kurzen says, "just going to the market, to church, finding a job. I could relate to these women—I never realized how vulnerable women could be if society allows them to be."

Showcasing that vulnerability while protecting the anonymity of her subjects was a challenge, but Kurzen worked with the women to come up with creative ways to avoid showing their faces. She took the photographs using a medium-format camera that was small enough for the women to see her face as she took their portraits. "[For them] to give that trust is beautiful."

Marie herself came up with the concept of being photographed in the river. "She is the most brilliant young woman—ambitious, smart, educated. She wants to do her studies and become a journalist. She had a great idea to take the picture in the water. We had a long conversation about why and how. And she said, 'It's like I'm doing laundry, a symbolic thing; I want to wash it off me, look toward my future." A future in which Marie—and women like her—might not need to be anonymous anymore.