It was an early March morning on Washington, D.C.'s K Street—the boulevard synonymous with political influence the way New York's Fifth Avenue is with high-end shopping or the Champs-Élysées with love. Lobbyists and lawyers, bureaucrats and bankers gathered for a conference on America's infrastructure nightmare. And many of them were in a rut so deep that not even the model of sleek subway cars from Mitsubishi Heavy Industries next to the free coffee and croissants could lighten their mood.

They all knew President Donald Trump has been promising a massive plan to rebuild America's infrastructure since the day he descended that Trump Tower escalator in 2015 and announced his unlikely bid for the White House. And they all knew that no plan has yet been announced. And that makes many people antsy, even angry. Those who live off government largesse are eager for his rhetoric to turn into a golden shower of dollars. And those millions of Americans stuck in traffic (the average driver is jammed up 43 hours a year) or rolling their eyes at the (sad!) state of New York City's LaGuardia Airport—both former Vice President Joe Biden and Trump have likened it to a Third World country—want someone (anyone!) to do something (anything!) to fix this damn mess.

Related: Trump to unveil $1 trillion infrastructure plan this year, says Transportation Secretary Chao

While shoveling down Nutella crepes and green-power smoothies, plenty of the experts at that power event were also chewing on grave concerns about what the president will propose to, as he promised, "completely fix America's infrastructure." Obama administration Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood, a former Republican representative from Illinois, says "America is one big pothole" and laments that raising the gas tax or taking other reasonable measures to fix the country's transportation rat nest are off the table. Senator Sheldon Whitehouse, a Democrat from Rhode Island, fears that Trump's plan could turn into corporate welfare, a boondoggle for private investors. Even conservative Texas Republican Representative Blake Farenthold is doubtful that the rosy scenarios for getting a few public dollars and using them to entice the private sector to build tons of roads will work. "That's going to be tough," he says.

Later that morning, a few blocks away at the White House, the president met with his infrastructure team. Those assembled included Secretary of Transportation Elaine Chao, who is the wife of Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, and top advisers such as the then-ascendant Steve Bannon, as well as the New York billionaires Trump tapped to head a kind of business advisory board for his infrastructure push: Richard LeFrak, whose family's company is a behemoth of New York real estate, and Steven Roth, one of Gotham's largest realtors. (Roth has helped bail Trump out of at least one major real estate deal and helped his son-in-law, Jared Kushner, out of another.) The president told the group he wants to see money going to roads and bridges and sewer repair right away, and he doesn't want the states to screw around with regulatory delays. But anyone hoping for actual, you know, details was played for a sucker.

Trump didn't present his plan that day, or any day since. We have only that glint of an idea he flicked at in his joint address to Congress in early March, when he called for a $1 trillion investment in infrastructure. But he left it unclear how much of that would be direct government spending on roads and bridges and the like, and how much would be tax breaks to induce private companies to build such things. Adding to the confusion, a couple of weeks later, when the president tossed his wish-list budget to Congress—the one that got all that attention for hiking defense spending and bringing down the curtain on the National Endowment for the Arts—there was no $1 trillion line item for roads and bridges. In fact, his proposed budget had less money for infrastructure than is currently being spent, and programs such as Community Development Block Grants, or CDBGs, were cut back significantly.

Trump and administration officials keep saying a big infrastructure plan is coming, perhaps even tacked on to some other bill—" I may put it in with something else because it's a very popular thing ," Trump told The New York Times in early April. But so far, everyone is just guessing. House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi keeps saying, "Where's the bill? Show us the bill!" and Republicans don't seem to know much more than she does. The House's top member on infrastructure issues, Bill Shuster, a Pennsylvania Republican who chairs the transportation committee, guesses that Trump might tuck his infrastructure plan into a must-pass reauthorization of funding for the Federal Aviation Administration later this year. Some think it could get stuffed into a big tax reform proposal, but tax reform seems improbable since many Democrats vow to block any package until Trump releases his returns. And that seems about as likely as him swapping Mar-a-Lago for a sixth-floor walk-up.

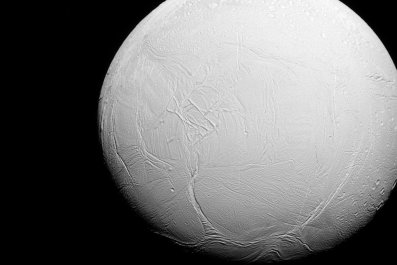

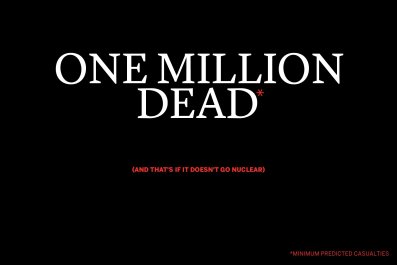

For a president with high negatives, a massive infrastructure intervention has the unusual appeal of being popular with everybody. (During the presidential primaries, both Trump and Bernie Sanders often cited the high-quality roads and airports in Abu Dhabi, the United Arab Emirates or Inchon, South Korea, while bemoaning the shabby state of America's infrastructure.) Polls show that a huge percentage of Americans favor spending more on infrastructure, which is no surprise in a country where roads are potted, sewer pipes leak, bridges buckle and dams burst. In March, the American Society of Civil Engineers gave the country a D+ in its much-anticipated (as least in the construction industry) quadrennial report. The ASCE report also said it would take something like $2 trillion to get the country's infrastructure into just fair shape.

That's a staggering price tag, but this is a moon shot everyone seems to want. This could be a great time to rally around a widely acknowledged problem (there's no fight over fake news; everyone can see the potholes), and it's a decent time to borrow big (interest rates are low) to fund these much-needed repairs. But that's unlikely, because in Washington, D.C., quotidian fights over money derail even universally shared goals: "Let's have great roads and world-class airports!" And it's not just another example of congressional paralysis. All across the land, voters demand a solution but are unwilling to pay the taxes for it. Roads aren't the only things that are rutted, corrupted and antiquated. So is the political system that probably can't fix them.

Yo! Stimulate This!

How to pave the nation's roads, build its canals and make its natural abundance available for commerce has been a pressing issue going back to the Founding Fathers. Alexander Hamilton favored an aggressive program of debt-financed "internal improvements" for roads, canals, ports and the like. His ideological heir, Kentucky Senator Henry Clay, made his name in the early 1800s by promoting an "American system" of improvements that was even more aggressive than Hamilton's schemes for making the national government responsible for transportation needs. In the 1850s, Abraham Lincoln's new Republican Party was committed to stopping the expansion of slavery but also big on infrastructure projects, most notably the construction of the transcontinental railroad. The apotheosis of government infrastructure was the building of the interstate highway system in the 1950s under another Republican president, Dwight Eisenhower. His sprawling ribbons of concrete changed America, fueling the growth of the suburbs and the mass adoption of the car.

All those politicians knew that infrastructure projects make an economy hum. When done well (as opposed to demolishing neighborhoods or building bridges to nowhere), they make life better for many. And in times of economic recession, putting people to work on shovel-ready jobs provides an important Keynesian stimulus—albeit one that has less punch in a near-full employment economy, when you're just turning baristas into bricklayers. That was the idea behind the Obama stimulus package of 2009, which would have had more road monies if Republicans hadn't insisted that the package be scaled down.

The United States is no longer in a grinding recession, but Trump was right to focus on infrastructure during the presidential campaign. The country had been spending about 20 percent less on water and transportation infrastructure than in 1959—and that's while having to meet the demands of today's much older and bigger network of roads and sewers. The cost of bringing it up to a better standard is, says Greg DiLoreto, the former head of the Tualatin Valley Water District in Oregon and infrastructure chair at the ASCE, "the price of a latte per day, per family—not even for an individual."

The Bridge From 1840

When the Oroville dam burst in Northern California earlier this year, it was yet another reminder (like the collapse of an interstate highway bridge in Minnesota in 2007) that infrastructure repairs are urgently needed—north, south, east and west, red state and blue state, big city and small town. In Washington, D.C., the famed Memorial Bridge needs serious repairs. In northern New Jersey, the Portal Bridge on the northeast rail corridor is 104 years old, based on a design popular in Britain in the 1840s and partly made of wood. Across the country, ASCE found 60,000 bridges that are structurally deficient. Jennifer Cohan, Delaware's transportation secretary, carries around a piece of concrete that fell from one of the state's bridges. She doesn't need to be hit over the head with a brick to know America is falling apart.

But the Trump plan, at least what little we know about it, seems unlikely to get anyone safely off that Victorian-era bridge, let alone fix the many other infrastructure blights, like the nation's electrical grid. The germ of it is an infrastructure paper written by economist Peter Navarro, a business school professor turned trade adviser in the protectionist Trump White House, and Wilbur Ross, the zillionaire secretary of commerce. It's a critique of Hillary Clinton's traditional call for government-financed infrastructure spending and instead promotes tax cuts as a way to get private industry to pay for road, bridge, sewer and other repairs.

Translation: Trump doesn't want the federal government to spend a lot of money hiring people to pave roads and build bridges. He likes a tax-cut plan designed to get the private sector to build roads and bridges that would turn a profit for them. The creative accounting is that you give $167 billion in tax cuts over 10 years, and it spurs something like $1 trillion in private investment.

In theory, there's nothing wrong with private investment in infrastructure, but many desperately needed projects have little chance of ever profiting investors. The folks who helped build a toll lane in suburban Washington, D.C., stand to get a good return on their investment because the roads there are crowded, and there are plenty of wealthy drivers willing to pay for the so-called Lexus lanes. But there's no realistic prospect of a payout for fixing, say, a rural road in West Virginia. Speaker of the House Paul Ryan blithely ignores such inconvenient truths as he touts his belief that every $1 in targeted tax cuts can spur $40 of infrastructure spending. Buried in an interview Trump did with The New York Times is his skepticism about private financing. " We haven't made a determination as to public/private," he said. "There are some things that work very nicely public/private. There are some things that don't." As with his flip-flops on so many issues, such as Syria, where he went from adamant non-interventionist to lobbing cruise missiles at Bashar al-Assad's air force, no one can be sure what to expect from this White House.Another problem with the tax-cut approach is that it likely winds up subsidizing projects already underway rather than spurring new investment. "We don't want to get into a situation where it's a giveaway for businesses who are going to do this anyway," says Sheldon Whitehouse, the Democratic senator from Rhode Island.

"Private investment is important, but it's by no means sufficient," says Ed Rendell, the former mayor of Philadelphia and governor of Pennsylvania who co-chairs Building America's Future, a bipartisan group pushing for more infrastructure investments. "Tax credits can only do so much. The lion's share has to come from the federal government. Don't screw around."

The International Finance Crapshoot

Even if those tax cuts would work, it doesn't really matter because Trump doesn't have a funding mechanism to pay for them. There are ideas being kicked around Capitol Hill to get at the trillions of dollars American corporations have squirreled away overseas because they don't want to bring those dollars home for fear of facing the U.S.'s notoriously high corporate tax rate. If the government dramatically cuts taxes on repatriated money, the thinking goes, corporations will have more to invest here, and the government will pick up tax revenue, which can be earmarked for infrastructure. That sounds like a Hail Mary pass only because it is. And it seems unlikely such an "accommodation" of tax-ducking multinationals could ever get through Congress.

Another downer: Assume for a crazy-dreamer moment that an infrastructure plan based on tax cuts is feasible. It still wouldn't do much for the unemployment rate because it is more likely to shuffle jobs around than create new ones.

Want a Hoover Dam–sized caveat? Even if Trump could pass his plan and it works well, it would only be a one-time shot. It doesn't get at many of the underlying causes of what ails American infrastructure. For instance, Americans pay for highways largely through the federal gasoline tax. But that tax hasn't been raised in 18 years, and at 18.4 cents per gallon for regular fuel (24.4 cents for diesel), it's negligible and overwhelmed by the gyrations of fuel prices. In an era of cars getting better and better gas mileage, it brings in even less revenue every year. Five years ago, Congress had to raid all kinds of other funds and engage in various fiscal gymnastics just to keep money going to the trust fund. That problem will only get worse as gas mileage improves.

Any proposal to raise the gasoline tax is doomed in a Republican Congress, but if it's not in Trump's plan, it should be, as should be some novel ideas, like taxing people based on the number of miles they drive, rather than how much gasoline they consume. That would involve putting wireless meters on people's odometers, a modest bit of technology not that different from electric meters in the home but likely to raise an outcry about privacy from those who fear the government is tracking them.

So far, though, Trump's big infrastructure initiative is bumping down the same troubled path he took on health care. Talk in glowing terms about a solution, offer no details and build no public support for them—then drop a plan no one really likes and watch it die.

That could be a criminal waste of an opportunity because, as a builder, Trump has some cred on this issue. At a meeting of building trades workers in April, Trump boasted, "Did you ever think you'd see a president who knows how much concrete and rebar you can lay down in a single day?" Maybe not, but the wobbly foundation of his infrastructure plan suggests there are a lot of things about being president he still doesn't know.