Swinder Singh was asleep at her home in north London when she got the call. In the blurry hours of the early morning, she listened as the voice on the end of the phone told her that her younger sister Seeta Kaur, 33, was dead. Seeta's twin sister, Geeta, delivered the news.

Earlier, Seeta's brother-in-law, Jitendra Saini, had called her father and explained that Seeta had died of a heart attack while staying at his family's home in Kurukshetra, northern India, with her husband and four children. In keeping with Hindu custom, Jitendra said, his family would cremate her.

Seeta's father pleaded with Jitendra. "Do not cremate her," he told him. "We want to see her for the last time." His plea wasn't motivated only by grief—he was suspicious. His daughter's husband, Pawan Saini, an Indian citizen and British resident whom he had introduced to Seeta, had been physically abusive for years, her family says. Twice, in London, in 2010 and 2013, Seeta's sisters had seen him throttling his wife. Her family also says Pawan repeatedly demanded that she let their eldest son move to India to live as something of a surrogate son to Jitendra and his wife, who did not have children of their own. Had Pawan taken Seeta, a British citizen, to India, so that he could kill her in a country where the judicial system is riddled with corruption?

In London, in the hours after they heard the news, Seeta's family hurried to book flights to New Delhi. As they packed their bags, her father, a retired grocery store clerk, dispatched his nephew in Mathura, India, to make the five-hour drive to Kurukshetra. The family wouldn't arrive until April 1, 2015, a full day later. Someone had to guard his daughter's body.

When the family eventually arrived in Kurukshetra, dusk was falling. The nephew was still at the house, preventing Jitendra and his family from cremating the body. A large group of mourners were also present, filling the ground floor and spilling onto the street. "I walked into the living room, and you can see there's a refrigerated coffin box, glass, and Seeta's covered from head to toe with blankets, so you couldn't see the body through the glass," Swinder says.

Swinder began forcing her way through the crowd. Once she was by the coffin, she tried to open the box. "They were pushing me back, shoving me, saying 'don't touch,'" she says. Fighting them off, she lifted the lid and pulled the covers off her sister. "I can see all her neck from her upper chest is all bruised, blue and green," Swinder recalls, her voice cracking. "So it's real, you know. You can see all around her neck. She's been bruised."

Swinder remembers turning and screaming at the crowd gathered behind her: "She didn't die of a heart attack! You've murdered her! You've strangled her!"

In 2000, the United Nations estimated that each year 5,000 women are killed by relatives for supposedly bringing dishonor upon their families. The figure for these so-called honor killings is both outdated and likely inaccurate. A spokesman for the U.N. Population Fund tells Newsweek that since most honor killings happen "in areas where the social-cultural foundations are more accepting of this type of activity," they are often not reported or passed off as natural deaths. (The organization says it updates its statistics periodically and has not yet produced an update on the 2000 figure.) Some countries have their own independent estimates for the number of honor killings, but the familial collusion that frequently surrounds these deaths renders the figures unreliable.

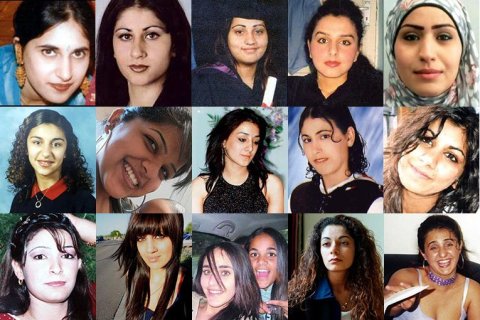

Rights groups in the U.S. and U.K. believe that transnational honor killings—when family members lure victims overseas to kill them—are a growing phenomenon. From 2010 to 2014, the U.K. human rights think tank the Henry Jackson Society recorded 29 cases of honor killings of people who resided in the U.K., based on media reports. Activists say that what's striking about the U.K. figure is that 11 of the murders were committed overseas, all of them in Pakistan. It's impossible to say what the true extent of these out-of-country killings are, the society warned: "There are no reliable figures on the total number of female British residents and/or citizens who have been killed abroad in the name of honor."

Perpetrators of these crimes apparently believe that they stand a better chance of getting away with an honor killing if it occurs in countries, like Pakistan and India, whose police forces and judicial systems suffer from corruption. Officials in the victim's country of residence are less likely to find out about such a murder, and even if they do, police cannot just travel abroad and launch their own investigation. Unless people close to a victim raise awareness of his or her death and pressure lawmakers to intercede, the crime will usually go unrecognized and unpunished.

In the U.K., the problem of transnational honor killings attracted widespread public attention in 2016. On July 20, a young woman named Samia Shahid was found dead in Pakistan. Her family had reportedly lured her to the country by saying her father was sick. When she arrived, her ex-husband, assisted by her father, allegedly strangled her.

Naz Shah, the member of Parliament for Bradford West—the electoral district in England where Shahid lived—moved quickly when Shahid's second husband told her about his wife's death. At Shah's urging, Pakistani police investigated Shahid's death, which her family had attributed to a heart attack. Officers have since charged both Shahid's ex-husband and father with her murder. Her second husband believes they killed her because they disapproved of her divorce and of him.

Transnational honor killings are particularly prevalent in India and Pakistan. As well as the 11 Pakistani cases the Henry Jackson Society has recorded, the Southall Black Sisters, a women's rights group based in southeast England, points to two transnational honor killings that happened in India. In 2007, a 70-year-old British woman was found guilty, along with her son, of ordering the 1998 killing of her daughter-in-law, Surjit Athwal, in India after Athwal allegedly had an affair. In 2013, a court charged Jagpaljeet Singh Kular with the 2007 murder of his wife in India, but the prosecution withdrew from the case, citing lack of evidence.

India and Pakistan are also where a large proportion of all honor killings happen. Using the U.N.'s estimate that 5,000 honor killings occur worldwide each year, the international Honour Based Violence Awareness Network (HBVA) says that around one-fifth of all such murders take place in India, while another fifth occur in Pakistan. Both countries are aware of the problem. In October, the Pakistani government closed a loophole that allowed the perpetrator of an honor killing to go free if the victim's family—who may have sanctioned the killing—forgives the murderer. (The law still allows the family to save the killer from the death penalty.)

In India, police historically recorded honor killings—assuming they were reported—as regular homicides. As a result, the Indian government had no indication of how many honor killings were committed each year, though it knew the problem was significant. In 2014, in an attempt to combat this, officials ordered police to list honor killings as a distinct category of murder. Despite this new law, the numbers suggest Indian police are still miscategorizing or overlooking hundreds of deaths. After the government's edict, Indian police recorded 251 honor killings in 2015, up from 28 in 2014. But even the 251 figure falls far short of the HBVA's annual estimate of about 1,000 honor killings in India each year.

Seeta Kaur's family believes she was one of these victims. They say that her husband felt she had dishonored him, shaming him in front of his family by refusing to give up her son to his brother. They alleged that he planned her murder before they left for India, luring her to the country by falsely claiming that his mother was sick. Her family adds that he also left his job before she died, suggesting that he had no plan to return to the U.K.

Pawan Saini denies killing his wife, and he disputes every allegation by the Kaur family that Newsweek put to him by phone. In response to his in-laws' allegations of domestic violence, he tells Newsweek's translator: "In London, even if you slap a woman, she can go to the police station. I never touched her. I never did that. Obviously, we had arguments like any other family, but I never laid a hand on her."

Pawan claims that he and Seeta discussed their son moving to India only once or twice. He says he told her they were going to India to celebrate their twins' first birthday. (Their other two children were then aged 6 and 8.) He also says he never resigned from his job but kept asking his boss for extensions to his vacation. After Seeta died, Pawan says he decided to remain in India but didn't notify his boss of the decision. (He showed Newsweek one WhatsApp message in which he told his boss he would return on March 24, not March 4 as planned. His employers declined to comment on his history with the company, citing data protection laws.)

Southall Black Sisters says Pawan is lying. The organization, which is campaigning for British police to look into Seeta's case, has evidence from 26 witnesses, including family, friends, colleagues and clients, that contradicts Pawan's claims. The witnesses say they either saw him being physically abusive toward both his wife and her young children or heard Seeta describe the alleged violence. (Newsweek has seen a redacted summary of evidence from the 26 witnesses.)

Southall Black Sisters also showed Newsweek a letter Seeta had sent to her children's school principal. In the document, she asks if they can have time off from February 8, 2015, to March 3, 2015, to visit their allegedly sick grandmother in India. The letter makes no mention of celebrating the twins' birthday, which Pawan says was the main point of the trip. The group also sent Newsweek a copy of his P45, a document British workers receive when leaving a job, that shows his employment ended on March 22, 2015, nine days before Seeta's death.

Once Swinder Singh had seen inside her sister's coffin, she decided she was right to suspect Pawan. Her family had already made inquiries in New Delhi about repatriating the body and Swinder and her father told Pawan they needed to take Seeta back to the U.K. They say he agreed to sign the necessary paperwork at the local police station in the morning. As Pawan's family laid out bedding, Swinder and her family settled down to try and sleep.

As the sun rose on April 2, 2015, they demanded that Pawan take them to the police station to sign the repatriation forms. They wanted to get Seeta's body away from her husband and to the U.K. for a proper post-mortem.

Pawan delayed, Swinder says, for a few hours. Then, at around 10 a.m., he came upstairs and sat before her father. "He says to my dad: 'I've cremated her,'" Swinder says. "It was shocking. My dad, he just froze." In response to the family's horror, Swinder remembers Pawan telling them: "She was my wife."

Pawan, speaking through a Newsweek translator, disputes Swinder's comments. "I went upstairs and said we're going to cremate your daughter, and they said they didn't want to come," Pawan says. "They didn't give a reason." Pawan added that if the family thought he had murdered Seeta, why did they wait until the day after they arrived in India to go to the police? (Swinder says the family was in shock and thought it would be easier to get the necessary documents signed in the morning.)

After Pawan delivered the news about Seeta's cremation, Swinder says she ran downstairs, where the coffin still lay, and stopped short. Had Pawan lied to them? Inside the coffin, the blankets were arranged in the same way as the night before. For the second time, Swinder lifted the lid and pulled down the covers. There was nothing inside. Pawan had indeed cremated her sister, and in doing so, Swinder believes, he destroyed the evidence of her murder.

In a daze, she left the house with her father and brother and began asking for directions to the local police station. Swinder says 40 of the mourners followed them to the station hoping, she thinks, to intimidate them and run them out of Kurukshetra.

At the police station, the family found the officers lethargic and bored. They couldn't compile a report, they told Swinder, because their electricity was down. A few hours later, an officer named Ram Kumar interviewed the Saini brothers and then went to speak to the Kaur family. "Just take your son-in-law and his four children back to the U.K. and don't do the report," Swinder recalls him saying.

The family ignored the officer and filed a report. For 21 days, they remained in India, begging the police to arrest Pawan and properly investigate Seeta's death. Swinder says the police kept reassuring them that they were looking into her sister's case, but she saw little evidence of this. The officer, who has moved to another police station, repeatedly refused to speak to Newsweek about Seeta's case and the allegations her family has made against him.

Eventually, Seeta's family flew back to London, forced to leave the four young children with their father. Since the police had not charged Pawan, her family had no claim to them. Still, they reasoned, Seeta was a British citizen—surely the U.K. police would want to pursue her case.

But, as Swinder and her family were soon to find, the law wasn't on their side.

There is only one piece of U.K. legislation that applies to transnational honor killings. The 1861 Offences Against the Persons Act covers domestic and transnational murders, as well as acts of manslaughter. The law states that any British citizen who commits murder or manslaughter abroad can be investigated, tried and punished in the United Kingdom. But the 156-year-old law doesn't include immigrants who do not hold British citizenship, even if, like Seeta's husband, they are legal permanent residents and even if their alleged victims are British citizens. (The equivalent laws in the United States and Canada similarly legislate only against nationals. France, Germany and Australia—countries that also have significant immigrant populations—do legislate against nationals and residents who commit murder abroad.)

In the U.K., Nusrat Ghani, a lawmaker of Pakistani descent, submitted a bill to Parliament addressing honor killings and violence against women that happens abroad. But though she told Parliament Seeta's death was one of the cases that compelled her to write the bill, it provided only for "the prosecution in the United Kingdom in certain circumstances of citizens of the United Kingdom" who commit overseas honor killings. The bill did not make it to a second reading.

For Seeta's family, the gap in the 1861 law reduces their chances of getting what they see as a just resolution to the case. Six months after the family returned to England, the Indian police told their lawyer in India, Simranjeet Singh (no relation to Swinder Singh), that Seeta had been murdered, but the killer remained untraced. Case closed. Pawan denies the police ever reached the conclusion of murder.

The police decision disappointed Seeta's family. Pragna Patel, founding member of the Southall Black Sisters, tells Newsweek that the Indian police never interviewed Seeta's family and friends. The conclusion of the investigation meant the family had hit a wall. Indian officials believed the matter over, and U.K. law didn't allow for the prosecution of Pawan. A British citizen was dead, and her own government seemingly couldn't help her.

Simranjeet Singh is frustrated with U.K. officials. "It takes years to get justice in India," he says, speaking from his office in Chandigarh in northern India. Blaming the country's inefficient and bureaucratic legal system, he adds: "Often justice is better rendered by a developed foreign authority. I do not understand why the police have not taken action in the U.K."

The lawyer says that the family's claim that Pawan tried to strangle his wife in London should prompt the city's police force to carry out their own investigation. In an emailed statement, London's Metropolitan police told Newsweek they are responding to queries from the Kaur family's U.K.-based lawyer. (In September, Shamik Dutta, the British lawyer for the Kaur family, asked the police to open their own investigation—including examining Pawan's actions prior to leaving the U.K.)

The British police don't have to take action on overseas murders, but that doesn't mean they can't. If U.K. police officers believe a foreign case merits their involvement, they can offer their assistance to the country in question. This happened in 2014, following the murder of two British backpackers, Hannah Witheridge and David Miller, in Thailand. Their deaths, which were particularly brutal, attracted widespread media attention. Then–U.K. Prime Minister David Cameron leaned heavily on Thai Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha to allow British police officers to observe the investigation. At the time, Thai police had arrested two suspects, and Cameron wanted U.K. police to ensure the arrests were the right ones. The Millers and Witheridges, who had expressed concerns about the investigation, subsequently said they believed the Thai police arrested the right people.

Seeta's case did not make the front page of a single newspaper. Nor did the Metropolitan police offer to investigate her death. In a leaflet calling for justice for Seeta, the Southall Black Sisters claimed that Britain is less interested in intervening in cases concerning "non-white British nationals." In response, the U.K. Home Office tells Newsweek that individual police forces, and not the government, decide which cases to investigate.

Almost two years after Seeta Kaur's death, the family seems no closer to getting justice. Her four children—a son aged 10, a daughter aged 8 and twins aged 3—remain in India with their father, Pawan Saini, despite a British ruling calling for their return. Swinder Singh, who hasn't been back to India since her sister's death two years ago, doesn't know how they are. She is afraid that she will never see her nephews and nieces again.