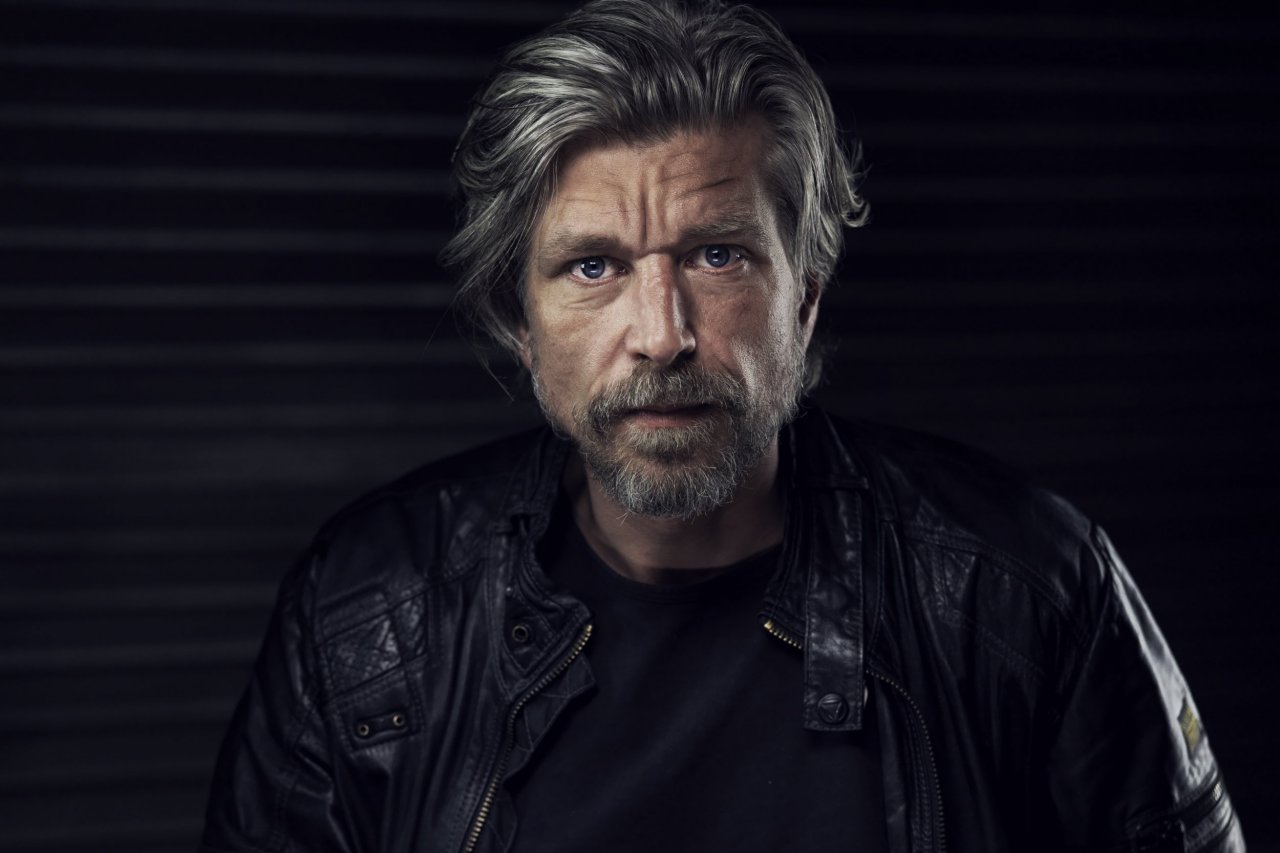

The simultaneous expression of the gigantic and the minuscule, the dull and the piercing, is the achievement of Karl Ove Knausgaard's My Struggle, an autobiography so ambitious that it spans some 3,600 pages, meted out in six volumes. The books became an international literary sensation for the cool rigor with which the Norwegian writer probes the intimate contents of his life—interlaced, as a life inevitably is, with the intimate content of the lives of family and friends, not all of whom are happy with the attention. A dashingly morose, angular, floppy-haired soul, he has, in the years since the first volume was published in 2009, submitted to countless interviews and readings, flaying himself aloud each time he squares the pleasure of writing with the pain of having written.

Knausgaard has spoken of being tortured by his success. Nevertheless, he persists. While English-language readers await publication of the final volume of this magnum opus later this year, here is Autumn, the first of four volumes (published in Norway over the past two years as a "seasonal encyclopedia") that constitute a variation on Knausgaardian introspection: discrete, fragmented meditations prompted by the mechanics of daily life. My Struggle, a Postscript it is not. Autumn is a fleeting 224 pages, including dreamlike illustrations by Norwegian artist Vanessa Baird. And the work is translated by Ingvild Burkey rather than by Don Bartlett, the voice that English-language readers have come to know as Knausgaard's. So the words, while the author's, have an ever so faintly different accent, something plainer and more immediate.

That is no accident. Knausgaard has said he looks upon this project as a respite, a new form—a diary-like sketchbook in which he can experiment with describing the physical world he loves because it allows him, for a moment, to step back from being the Nordic Proust, to just a curious guy writing three pages each on things he thinks are worth three pages each: teeth, porpoises, chewing gum, rubber boots, faces and—because he is Karl Ove—vomit, labia, piss, toilet bowls and loneliness.

Three times, the diarist also includes an interlude he calls "Letter to an Unborn Daughter." And that's where My Struggle readers will reflexively sniff the air for clues to the man they like to think they know. Knausgaard is an acute, sometimes squirmingly honest analyst of domesticity and his relationship to his family; the unborn, unexpected daughter is his fourth child with Swedish poet Linda Boström Knausgaard. Norwegian-language readers already know what happened sometime after his daughter was born: Boström Knausgaard had a breakdown. Come Spring, the author writes about the crisis. The couple is now divorced.

In its self-lacerating honesty, especially about the author's agonized efforts to confront the legacy of his late alcoholic father, the accumulated mass of My Struggle exerts a hypnotic power. Autumn is too episodic for that. But there is still the precision of his attention and his ability to toggle from the concrete to the conceptual. Forever smoking his cigarettes, the husband and father takes his children to and from school, combs lice from their hair, fries sausages for their dinner. One day, he whitewashes his house, musing that the chore "feels good in the same way that kindling a wood fire and getting the logs to catch feels good.… Why is it good? I don't know." Then he figures it out with the sharp radiance that is his gift: "The feeling of being in the world and of being a part of it. To understand that when you touch something, you are actually touching something. Not just seeing, not just thinking, but grasping."

Autumn, by Karl Ove Knausgaard, translated from the Norwegian by Ingvild Burkey, Penguin Press, $27.