Hell hath no fury like a fan scorned. In 1979, when Bob Dylan issued Slow Train Coming, an album that made plain his born-again conversion as an evangelical Christian, devotees felt disillusioned, if not duped. How could such a committed skeptic, a man possessed of endless probing and independent thought, buy into this or any orthodoxy? What place did the nuanced observation of this artist have in the rigid script of the believer? Slow Train found Dylan paraphrasing Scripture in ways that struck the agnostic as condescending, condemning and small.

Of course, Dylan had pulled stark switcheroos before. In 1965, he stunned many by going electric, but the boos soon disappeared. Five years later, this avatar of originality frustrated fans again with the release of an album of tepid covers, Self-Portrait, inspiring one of the most stinging first lines of a Rolling Stone review: "What is this shit?" A mere six months later, Dylan redeemed himself with the beautifully ruminative New Morning.

But Dylan's three born-again albums, released between 1979 and '81 (including Saved and Shot of Love ), soured many for years. I was a teen at the time, and my Dylan freeze lasted until 1989's Oh Mercy, and in the wake of what followed—years of superb music and performances—there seemed little reason to revisit what many would call Dylan's lost period.

Trouble No More, a new boxed set, aims to change that, with eight CDs and one DVD of material his label, Columbia, is calling Dylan's "gospel years." (Sounds a lot less loaded than "born-again years," right?) When I listen to the music now, remorse has replaced my scorn. Oh me of little faith! The performances are a revelation.

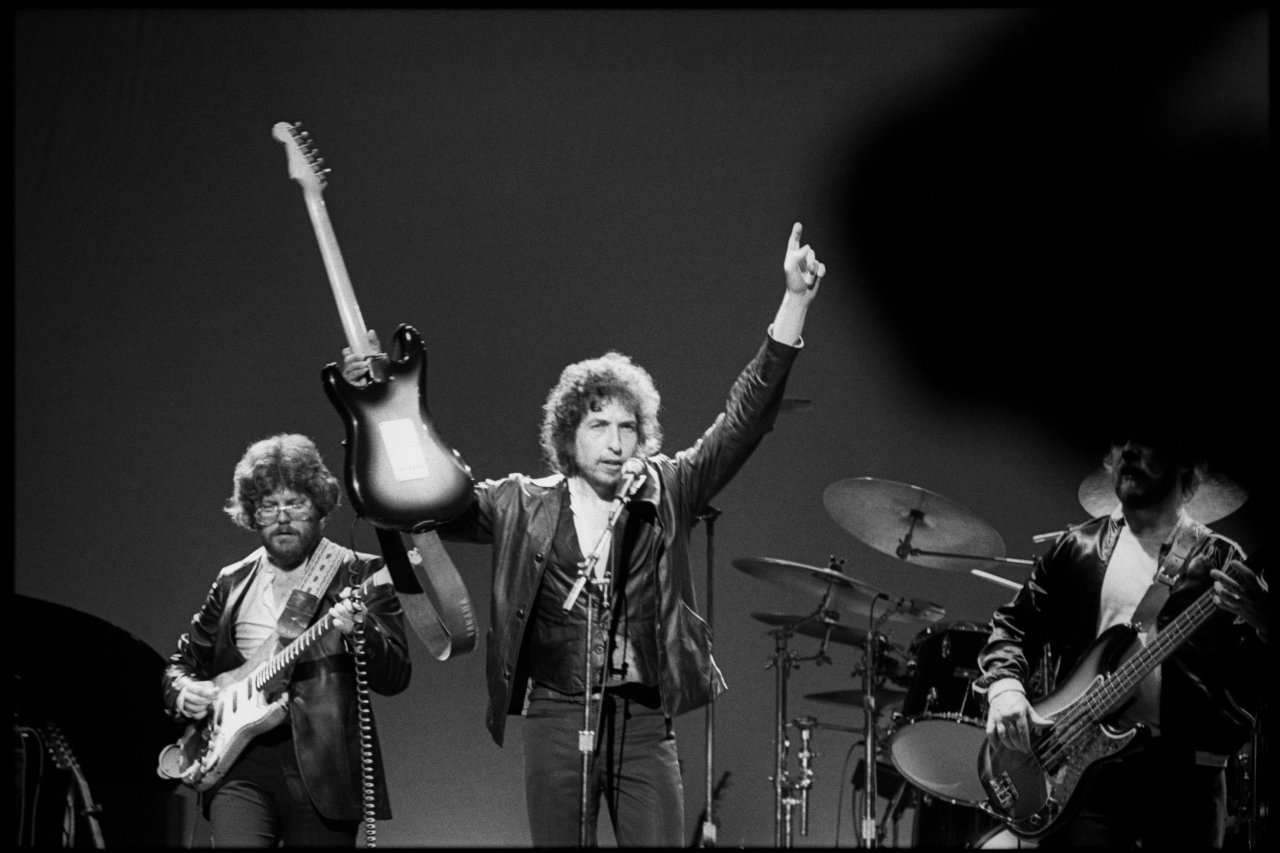

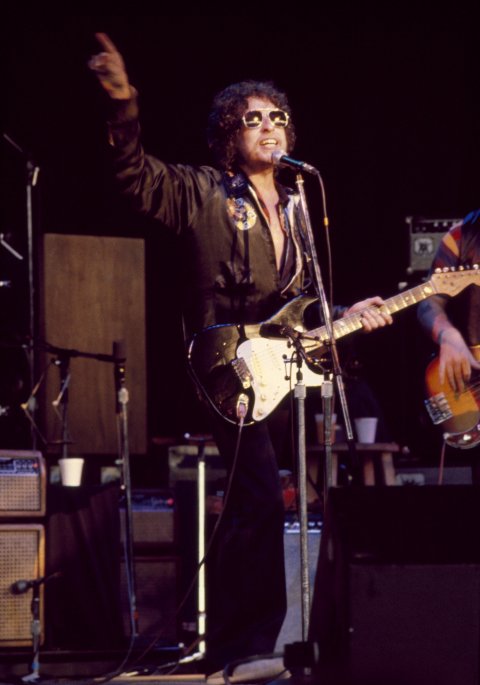

One caveat: The tracks included aren't the original studio recordings, which, to this ear, still sound constricted, self-conscious and didactic. Instead, the set focuses on the wildly dynamic live performances from concerts between 1979 and 1981. The stark contrast between studio and live performance makes sense. Dylan was taking his message directly to the people in real time back then, and you can hear how jazzed he was by the experience. Seldom has his singing sounded more engaged; rarely has his band mirrored him with such urgency and edge.

The shows, featuring shifting musicians, often included Spooner Oldham on churchy Hammond organ, Tim Drummond manning a funky bass, Jim Keltner pounding resounding drums and frequent Little Feat collaborator Fred Tackett on guitar. The backup singers, numbering up to five, played the convincing role of the choir, an ideal part for stars in their own right, like Clydie King, who brought her profound growl to "Shot of Love" and "Rise Again." It's a wholly new take on gospel music, fired by a rocking fervor.

Even so, some fans stormed out of those shows, mostly because Dylan wouldn't play older material and certainly not hits. He had relented some by late 1980, sifting some classics back in: "Girl From the North Country," for example, which has a gorgeous new gait in this reading, and "Forever Young," here kissed by R&B. Dylan made sure every song at these concerts was "busy being born" by adding different lyrics and new arrangements or shifting through fresh rhythms. Six distinct, increasingly inventive versions of "Slow Train" appear: One has a deep blues groove, kicked by Tackett's hard guitar leads; another features two axmen, with Tackett's stinging chords playing off Steven Ripley's wily wah-wahs. Surprising guest stars show up, like Carlos Santana whipping around "The Groom's Still Waiting at the Altar" or Al Kooper surging through "In the Summertime."

The mission behind this music inspired one of Dylan's most dense creative spurts. Fourteen of the songs included have never appeared in any form before. It's hard to believe he let a piece like "Ain't No Man Righteous, No Not One" slip away, but the take from '79, featuring singer Regina McCrary, has a depth of soul that might have been hard to re-create in the studio. It's even harder to fathom how "Ain't Going to Hell for Anybody," a lightning-paced stunner heard in two entirely different takes, was never recorded.

For a bit of fun, the boxed set includes a radio advertisement for the tour that features fans bitching about how deeply they hate Dylan's new guise. Perhaps we should have accepted that he moved—has always moved—in mysterious ways. It's not as if religious images hadn't figured in his music before, from the vengeful God of "Highway 61 Revisited" to the divine release of "Knockin' on Heaven's Door." When artists write songs of love, we never question the object of their affection, nor do we expect to share it. Why, then, did fans (myself included) challenge Dylan's clear passion during these years?

The faith Dylan expressed in his gospel songs came from what he claimed was an encounter with holiness in late '78. Several years later, that spell seemed to break, just as enigmatically. In 1997, he told Newsweek, "I find the religiosity in the music. I don't find it anywhere else. I believe in the songs." With Trouble No More, Dylan is giving us songs we believe in too.