All our presidents have been men; many of our presidents have also been dogs. Of the 45 occupants of the White House, 14 have been known or suspected, according to one estimate, to have engaged in amorous activity that wouldn't pass muster on Sunday morning, at least until fairly recently. Chester A. Arthur was already a widower by the time he was said to be conducting a romantic affair in the White House. "Why, this is worse than assassination!" he complained. John F. Kennedy may have disagreed. His own dalliances, however, are at least as famous as his accomplishments. If the latter seem conspicuously thin, the time he lavished on Fiddle and Faddle may serve as an explanation. The pool parties, as I understand them, weren't exactly legislative strategy sessions, either.

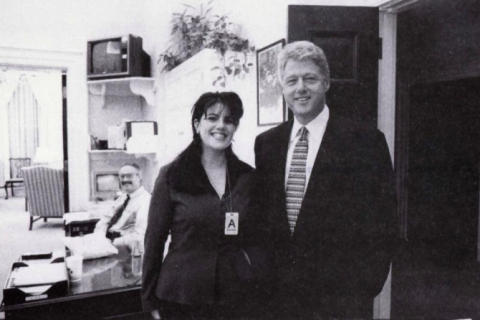

Then there's "The Big Dog," as Bill Clinton was sometimes known. If the innuendo in that nickname isn't apparent enough, he was also sometimes called "Slick Willy." Clinton was deemed "our first black President," by the novelist Toni Morrison. She famously applied that title in 1998, amid the investigation into Clinton's relationship with White House intern Monica Lewinsky, which would culminate in the president's impeachment. Clinton embodied "almost every trope of blackness," Morrison wrote, alluding to the president's "unpoliced sexuality."

The funk of sex hung on Clinton like a paramour's cheap perfume. He blew the sax on The Arsenio Hall Show. When, during an MTV forum, an audience member asked if his choice of underwear ran to boxers or briefs, Clinton answered honestly: "Usually briefs." Meanwhile, George H.W. Bush was struggling with the checkout scanner at a grocery store.

Clinton grasped policy, probably better than any president since. He also understood that people don't vote for policies. They vote for stories. And his story was of a prosperous superpower emerging victorious from the Cold War, a nation replenished and restored. We bought it in '92, then again in '96. We made his wife a senator, then secretary of state. We almost made her president. And maybe if her campaign had unmuzzled the Big Dog, she'd be back in the White House—only not in the East Wing this time.

These days, post-Weinstein, post-Spacey, with Alabama senatorial candidate Roy S. Moore spending his days fending off pedophilia charges, Willy does not seem especially slick. What may have been unpoliced in '92 cannot escape the wailing sirens of '17. Earlier this month, Senator Kirsten Gillibrand—Democrat of New York and Clinton protégé, a longtime benefactor of their largesse—was asked by The New York Times if Clinton should have resigned over the Lewinsky affair. "Yes, I think that is the appropriate response," she answered.

Boom. This was an attack from inside the Democratic redoubt, not another missile of deception and vitriol fired from Fox News. It came, no less, from a woman expected to make a serious bid for the presidency in 2020. The response from Clintonland was exactly as furious and outraged as one might expect, for Bill and Hillary have nearly as many loyalists as they do detractors. One of the faithful, former Hillary adviser Philippe Reines, quickly showed Democrats what awaited if they went the Gillibrand route instead of treating Clinton's history like something that belonged to a past distant, unknowable and, above all, irrelevant:

Ken Starr spent $70 million on a consensual blowjob. Senate voted to keep POTUS WJC. But not enough for you @SenGillibrand? Over 20 yrs you took the Clintons’ endorsements, money, and seat. Hypocrite.

— Philippe Reines (@PhilippeReines) November 17, 2017

Interesting strategy for 2020 primaries. Best of luck.https://t.co/KIsnfY4WLT

This was too late, however. In making her admission, Gillibrand committed the unpardonable Washington sin of speaking a truth everyone had agreed to keep quiet. Now that it's out, liberals finally can and should talk about Clinton's legacy, in the cultural context it deserves. They should not stop doing so because the discussion is exhausting or dispiriting, or because Trump has tweeted something outrageous.

Certainly, many younger Democrats do not hold Clinton's legacy as sacrosanct, immune to retrospection. "Kirsten was asked a question and gave an honest answer," says Alyssa Mastromonaco, a former top aide to President Obama. "I support her and hope that as we enter 2018 and the 20th anniversary of impeachment that people come to understand exactly what Monica endured."

Lauren Duca, a politically progressive columnist for Teen Vogue, goes further. "Bill Clinton's impeachment was blatantly politically motivated," she told me, "and as a result, he received a knee-jerk defense that conceals the wildly problematic nature of his behavior, even in some of the most progressive conversations. All of this is to say that he absolutely should have resigned. When it comes to removing predators from positions of power, political ideology is irrelevant," Duca says.

Will we miss Clinton if we banish him? Yeah, a little. After Clinton explained the Affordable Care Act to the American public much better than the president who signed it into law, Obama joked that Clinton was his "secretary of explaining stuff." Clinton talked about economic issues as Obama never could. But he also did things Obama never would. Clinton could use his charm to bring together the Israelis and Palestinians. He could also use it to lure an intern into the Oval Office.

If Democrats don't talk about Clinton, Republicans gladly will. During last year's presidential election, then-candidate Donald J. Trump invited as his guests to the second of three debates several women who'd accused Clinton of sexually assaulting or harassing them.

He must have known he wasn't going to rattle Hillary, who'd continued to endure rumors about Bill's behavior well into this millennium (see: Air Fuck One). The greater purpose was to remind Democratic voters, Hillary's people if not Hillary herself, of the Clintons' original sin. The women reminded Americans of something genuinely sinister about Clinton. In doing so, they called into question his entire legacy. They also distracted from Trump's own manifold alleged transgressions.

I reached out to one of those women, Juanita Broaddrick, who has long maintained that Clinton raped her in a Little Rock hotel room in 1978. She agreed with Gillibrand's assessment. "I think the moral decay of our society that we see today is a direct result of their years in power," Broaddrick told me in a text message, referencing both Clintons. "If he had resigned, it would have said, 'What I did was wrong, and it will not be tolerated.'"

Broaddrick, and other Clinton accusers, used to be smeared and dismissed, but that's no longer the case. Michelle Goldberg, an op-ed writer for The New York Times, recently wrote a column titled, simply and powerfully, "I Believe Juanita." Not a week later, her colleague Ross Douthat, The Times' resident conservative scold, attempted something similar in "What If Ken Starr Was Right?"

It is a convenient time to beat up on Clinton. But it is also the right time, as the treatment of women undergoes an examination it hasn't had since the second wave of feminism more than 50 years ago. The Clintons managed to hide behind charges that a "vast right-wing conspiracy" had sought to undermine Bill's presidency, and that his female accusers were but foot soldiers in that battle. Two opposite things can be true, however: Yes, conservatives badly wanted to depose Clinton. They'd have had a much harder time doing so if he behaved with anything resembling dignity or decency.

It's no accident that this renewed focus on Clinton comes during the administration of a president who has been accused of sexual misconduct by more than a dozen women. Earlier this month, Trump effectively endorsed Moore, the Alabama candidate for Senate who has been accused of child molestation. "He totally denies it," Trump said of Moore. He sure does. Clinton denied it, too.

Donna Brazile was there, having worked on Bill's 1992 campaign. Twenty-four years later, she served as the interim chair of the Democratic National Committee as Hillary was in the midst of her own presidential run. I asked her the difference between Clinton's accusers and those of Trump and Moore.

"The difference: Clinton was impeached," Brazile told me. "Trump was elected president, and Moore is seeking to become a U.S. senator." In other words, he was punished for his transgressions, while the Republicans never have been.

Maybe so, but the impeachment was over Clinton's lying about the Lewinsky affair under oath. His accounting for Lewinsky has been lawyerly in its contrition. In 2004, he said of the affair, "I did something for the worst possible reason—just because I could." He has denied other, more serious allegations that predate his time in Washington.

It is astonishing just how much Clinton's legacy has been diminished. During the 2008 presidential race, the nation's "first black president" tarnished his standing with African-Americans when he said that Obama's campaign was "the biggest fairy tale I've ever seen." Eight years later, with his wife running for president again, Clinton came under fire from Black Lives Matter activists who blamed his 1994 crime bill for sending a generation of African-American men to prison. He defended himself in a long, embittered diatribe that included reference to "gang leaders who got 13-year-olds hopped up on crack."

It was hard to tell if Clinton only seemed out of touch or, rather, had always been out of touch and the fact was only becoming apparent in that moment. I want to believe it is the former, if only because time is fundamentally unkind to all of us, to all of our convictions. And yet I fear it is the latter.

Other parts of Clinton's legacy were embattled as well long before this #MeToo moment. The entire Trump campaign was a referendum on free trade and economic deregulation. Clinton didn't start either trend, but he did sign the North American Free Trade Agreement into law. And he did repeal the Glass-Steagall Act, which had for decades prevented banks in exercising the kind of complex financial engineering that, in 2008, would lead to a financial collapse.

Hillary Clinton had spent decades defending her husband's treatment of women. In 2016, she had to fend off attacks on parts of his legacy that seemed unassailable. In any other case it would have been monstrously unfair, a wife forced to explain—and assume—her husband's shortcomings. In the case of the Clintons, however, you always knew you were getting a Shaq-Kobe combination. Clinton is eternally in the plural tense, just like Kennedy or Bush. (Chelsea in 2024, anyone?)

But don't blame the Democrats for their long embrace of the Clintons, even if they do seem to be pulling back a bit. Politics is compromise, and sometimes the compromise is not with legislators but our own imperfect selves. A deeply flawed figure picked by the party to stop a countervailing political force. Does that sound familiar? It should, because what the left did with Clinton in '92, the right did with Trump in '16. We say we learn from our mistakes, and yet we learn nothing.

In both cases, voters were asked to put aside the idealism that is inherent to civic life and pull the lever on more cynical concerns: the composition of the Supreme Court, the future of Roe v. Wade. The president, in this conception of politics, is not the voice and spirit of a nation but, rather, the final rubber stamp on a partisan legislative agenda. Except he is a man, not a machine. Sometimes, his flaws are so flagrant, they lead him to falter, to vitiate our body politic with his own weakness. And in the end, that weakness is all that we remember.