The rally in Dothan, Alabama, opened with prayer, a furious verse from Psalm 5 hurled at enemies of the Lord: "Their heart is filled with malice. Their throat is an open grave." These messengers of malice were also presumably the enemies of Roy S. Moore, the former chief justice of the Alabama Supreme Court then running for the U.S. Senate as a Republican. Foremost among those enemies was The Washington Post, which had published the accounts of several women accusing Moore of extremely disturbing sexual misconduct. But they also included Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, who'd equivocated in his support of Moore, and Richard C. Shelby, the senior Alabama senator who'd taken his turn as Judas by declaring on national television that he would "absolutely not" vote for the fiery jurist.

Moore is a conservative Christian, and so were many of the supporters who attended that rally on December 11, 2017, just hours before polls opened across the state. The rally freely mixed religion and politics—several radiantly blond siblings came onstage to sing, and a boy definitely not old enough to drive held the microphone and said, "I thank the Lord that Judge Roy Moore has shown us in the past that he will stand up for our beliefs, and he will stand up for Jesus Christ."

Stephen K. Bannon took the stage more than an hour after the rally began. Unlike many of the other speakers, Bannon did not make a pandering allusion to the University of Alabama football program: He seems to have as much interest in sports as a tweed-clad intellectual.

Bannon also did not talk about homosexuality or abortion, the two issues Moore and his supporters are exceedingly passionate about. Instead, he cast the looming election as a battle between those who believed in the "Trump miracle" and those who want him impeached. He then rhapsodized to the almost entirely white audience about "the Hispanic and black working class," that would benefit from the Trump administration's stringent immigration policies.

"Economic nationalism does not care what your race is, your color, your ethnicity, your religion, your gender, your sexual preference," he said, the last of these added after a slight hesitation. Only one thing mattered: your American citizenship. "American jobs for American workers," he said, after mentioning the black and Hispanic working class again. The notion of work as a redemptive force is central to Bannon's thinking, as well as to his own habits. As far as I can tell, Bannon doesn't do much but work. Whether that fact is thrilling or terrifying depends on what you think of the work he does.

Twenty-four hours later, I sat with Bannon in a hotel room on the outskirts of Montgomery. We had both spent the evening at the RSA Activity Center downtown, where the Moore campaign had its headquarters. It was a campaign coasting on confidence. When I'd run into Moore adviser Dean Young earlier in the evening, he was certain that victory was assured. So were the hundreds gathered in the downtown Montgomery ballroom. The blond siblings sang again. The speakers who'd praised Moore as a man of God the night before did it all over again. Then the returns started to come in. Older people prayed. Stunned younger people stared at iPhones.

Moore refused to concede that night, but he'd lost, and Bannon knew it. As did his many enemies. "Suck it, Bannon," tweeted a jubilant Meghan McCain, daughter of Senator John McCain, Republican of Arizona, and herself a prominent conservative figure.

Bannon is reviled by many on the left, but he has just as many enemies on the right. Establishment Republicans fear his renegade populist campaign will ensure that Democrats score significant victories in the 2018 midterm elections. "He's a cancer," Charles J. Sykes, the popular, Wisconsin-based talk radio host who recently left the Republican Party, told me.

RELATED: Bannon says he's 'totally uncowed' by Roy Moore loss

Such calumny might wilt some, but not Bannon, who described his comportment after the Moore loss as "totally uncowed." He'd left the White House in August and in October promised a "season of war" against what he saw as the moribund Republican Party; McConnell, whom he accuses of disloyalty to Trump; and House Speaker Paul D. Ryan, whom he once called a "limp-dick motherfucker."

Bannon may not be beloved, but those he's trying to slay are also reviled in many quarters. Congress now enjoys an approval rating of 14.7 percent, according to Real Clear Politics. In August, McConnell's approval ratings with his Kentucky constituents were 18 percent. The more Bannon is maligned by powerful but disliked Republicans, the easier it is for him to paint himself as the truth-telling insurgent out to save the GOP.

"Steve Bannon should send Mitch McConnell a fruit basket," jokes Andrew Surabian, who worked with Bannon in the White House and now serves as his aide-de-camp. He may similarly find himself the recipient of an Edible Arrangement from Thomas E. Perez, the Democratic National Committee chair for helping, in the eyes of many, a Democrat win in this blood-red state. The Democratic National Committee has been vowing to implement a "50-state strategy" ever since the cataclysmic 2016 election. Have the Democrats found their perfect weapon in Steve Bannon?

In Praise of the Unreasonable

First to speak at the luncheon for black conservatives at the Willard InterContinental Hotel in Washington, D.C., was Senator Ron Johnson, Republican of Wisconsin. Deploying his Midwestern monotone to lethal effect, Johnson talked at length about S corporations and pass-through entities. When it came time for questions, a woman who called herself a "red-blooded black American" pleaded with Johnson to help the African-American community. He listened respectfully, mentioned some social program he was fond of, then talked about pass-through entities again.

Two hundred and fifty people had not come to this gorgeous neoclassical ballroom to hear homilies about tax brackets. Nor had they come for the Caesar salad wraps. They had come to hear Steve Bannon.

When Bannon was introduced by Raynard Jackson, founder of Black Americans for a Better Future, the super PAC that organized the event, phones went away; backs straightened. Jackson quoted George Bernard Shaw: "The reasonable man adapts himself to the world: The unreasonable one persists in trying to adapt the world to himself." Then Bannon the Unreasonable took the stage.

After the applause quieted, he began to speak in his customary style: allusive, free-flowing content delivered in the precise, confident cadence of a military officer (seven years in the Navy). Instead of standing at the podium, he paced the stage, dressed in a black sports jacket and black shirt. In a rare nod to sartorial decorum, his shirt was tucked into a pair of khakis. He looked like an agitated history professor crossed with a revival-tent preacher. Bannon is a practicing Catholic, but his true religion is what he calls economic nationalism. It is the principle he believes won Trump the White House and could ensure Republican domination for the next 75 years. "He's proven that economic nationalism works," Bannon says of the president.

RELATED: Republicans think Steve Bannon is a huge loser

Despite that surety, Bannon can be somewhat vague regarding what, exactly, economic nationalism entails. The clearest explanation I got came from Surabian, who says Bannon's economic nationalism has three pillars: regulatory relief for business owners, tax cuts for middle-class families and an infrastructure program for the poor. The first two are long-standing Republican dogma, while the third borrows from the Works Progress Administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt. But all three require, in Bannon's conception, a much less generous approach to both legal and illegal immigration. This thrills some and appalls others.

Bannon's outreach to African-Americans seems calculated, at least in part, to blunt criticisms that he is either a white nationalist or a white supremacist. While he has been called those things, as well as a racist, misogynist and anti-Semite, this is by no means a complete list of his alleged transgressions. It doesn't help Bannon's rep that Breitbart News frequently publishes articles that, while conventionally conservative in content, are topped with incendiary headlines referencing "lesbian bridezillas" or, in the case of neoconservative Bill Kristol, a "renegade Jew." Several of Bannon's former colleagues have attested to his decency in credible publications. These do not appear to have had the intended effect.

Deploying a line he would repeat days later in Dothan, Bannon explained to those black conservatives gathered at the Willard that "a central thesis" of his economic nationalism was "programs that stop the destruction of the black and Hispanic working class." He cited the billions of dollars the United States devoted to military campaigns in Afghanistan and Iraq, asking the audience to imagine if similarly generous amounts had been lavished on Baltimore, St. Louis and Detroit. "Have we lost a sense of our priorities?" he asked.

A woman in the audience answered loudly, somberly, as at church when some collective sin has been named: "Yes!"

Later, a member of the audience asked Bannon about the lack of minorities in senior West Wing positions. "It's inexcusable," he answered. "Just inexcusable. You can't defend it."

I saw Jackson a couple of nights later, at a party for Trump campaign alumni. He is clearly glad to have Bannon as an ally. At the same time, much of his work involves convincing people that Bannon is nothing like the image of him readily available in news reports, late-night talk show monologues and social media memes. This is a task frequently complicated by the words and deeds of Bannon.

"In the media's mind, it's inconceivable that a black person would agree with anything that Steve Bannon had to say," Jackson told me later. He says that while friends and business associates are initially skeptical, hearing Bannon talk invariably dispels their concerns. They are particularly intrigued by his argument that uncoupling the United States from its foreign obligations would give African-American entrepreneurs access to capital they have historically been denied. "I believe," Jackson says, "that Steve has the ability to pull together a coalition to blow people's minds."

Stephen of Arabia

In 1916, the British intelligence officer T.E. Lawrence arrived on the Arabian peninsula to organize the region's Arab natives in a revolt against the ruling Turks of the Ottoman Empire, who'd been there since the 16th century. Lawrence quickly gained renown for his grasp of what would make the Arab Revolt successful.

One year later, Lawrence published "Twenty-Seven Articles," in which he offered counsel to his countrymen. "Bury yourself in Arab circles, have no interests and no ideas except the work in hand, so that your brain is saturated with one thing only."

When I visited Bannon in early December, a biography of Lawrence was one of two books in his hotel suite. "The structure of this is really very much like the Arab Revolt," Bannon told me of the political movement he has been trying to build since he left the White House four months ago. The more practical aspects of that revolt have included his vow to run primary candidates against every Republican in the U.S. Senate except for Ted Cruz of Texas, and fielding House candidates. A war of that scale could cost well over $100 million, perhaps testing the patience (and wallets) of conservative donors who want to see electoral victories, not intellectual ones.

Bannon expressed an admiration for how Lawrence united disparate Arab factions without forcing them to cede their identity. He believes he can play a similar role for the right wing of the Republican Party, bringing together ideological tribes in a furious fight against establishment forces led by McConnell and Ryan.

For now, he is pulling together an informal alliance of conservatives who share his populist agenda. "What we're doing is reaching out to all these grassroots groups," Bannon told me in Montgomery, "whether it's the religious right, whether it's the Tea Party groups, whether it's the Dave Bossie groups." (Bossie is head of the conservative activist organization Citizens United and was deputy campaign manager for Trump during the 2016 presidential race.)

He concedes that Moore wasn't an ideal candidate. In fact, Bannon initially supported Representative Mo Brooks, Republican of Huntsville, who was knocked out of the primary by McConnell-aligned super PACs that spent $10 million on the race. McConnell's candidate (and, briefly, Trump's) was Senator Luther Strange, whom Moore defeated in a primary runoff.

"Judge Moore has never been, really, an economics guy," Bannon said. Put more bluntly, it is almost impossible to imagine Moore and Bannon in conversation. And given that Bannon's conversation includes frequent and dismayingly casual references to yuan-pegged petroleum pricing and the Nullification Crisis of 1832, he may find it difficult to field candidates who are able to connect with him and, at the same time, with suburban voters in Northern Virginia.

Related: Steve Bannon is not running for president, associates say

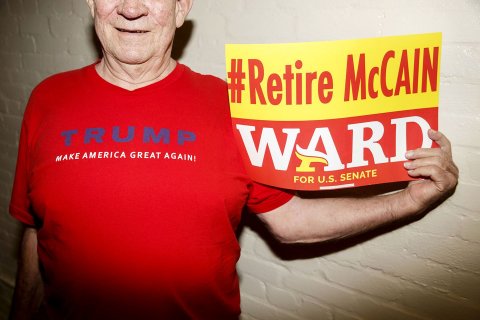

Bannon promises a stronger race from Arizona's Kelli Ward, who is running for the U.S. Senate. "Immigration and trade will be at the forefront of the Arizona race," he says. Bannon is also supporting Michael G. Grimm, a Republican from New York City seeking to regain his seat in the U.S. House. Grimm, who spent seven months in prison for tax evasion, is seeking to replace Daniel M. Donovan Jr., also a Republican. In May, Donovan was one of 20 Republicans to vote against the repeal of the Affordable Care Act. In October, Bannon endorsed his challenger, with Grimm tweeting a photograph of the two men posing at the "Breitbart Embassy," the Capitol Hill townhouse that serves as the Breitbart newsroom. Bannon also lives there.

Grimm says Bannon reminds him of his father's family, German and Irish immigrants who worked factory jobs in Brooklyn and saw little purpose in niceties, political or otherwise. "If President Trump is not successful, we're gonna lose our country as we know it," Grimm says. "Nobody understands that better than Steve Bannon." Apparently, Ryan does not share that view. Several days after Bannon endorsed Grimm, Ryan endorsed Donovan. That puts Bannon, once again, in the position of battling his own party instead of the Democrats.

What Bannon sees as principled battle, many Republicans fear is a suicide bombing. As the Republican strategist Tim Miller explains, Bannon's influence could lead establishment conservatives to tack right, as Ed Gillespie did, in hopes of attracting Bannon's support. (Gillespie lost in November's race for governor in Virginia.) Conversely, Republicans unwilling to do so, but also fearing attacks from Breitbart News for moderate positions, may choose not to run.

That's likely why, The New York Times reports, some Republicans " intend to kneecap" Bannon "before he has the chance to recover" from the Moore loss. Rick Wilson, the veteran Republican strategist, says the GOP needs to "beat his candidates down the moment he endorses them."

But Bannon, who calls himself a street fighter, may welcome such attacks, as they could sharpen the contrast between him and a moneyed but unpopular Republican establishment. That will, in turn, make him seem even more the tribune of the common man.

Bannon Agonistes

The second book in Bannon's hotel room was a bound printout of a congressional report on China. "I'm going back and getting every government document I can put my hands on on China," he said, brandishing the thick volume. "That's my light reading."

If Richard Nixon "opened" China with his visit there in 1972, Bannon is intent on closing it. To him, China's rise is frightening but its dominance of global affairs is not yet inevitable. He believes China's rise to superpower status has been abetted by what he calls "the Bush/Clinton crowd," which welcomed the nation into the World Trade Organization (Clinton) and failed to recognize it as a growing geopolitical menace (Bush).

That China poses a mortal threat to American hegemony is an unshakeable article of faith for Bannon. He told me he "absolutely" endorses the hawkish views of Peter Navarro, the Death by China author whose appointment by Trump as a White House adviser signaled that a trade war was coming. Bannon thinks the war is already here, and that Americans are as slow to recognize incipient doom as the Poles were in the summer of 1939, when the Wehrmacht gathered on Poland's western border.

"It's one-sided. They have all the forces of state power driving this," he says. He was alluding to China's most ambitious plans: a $1 trillion international infrastructure plan known as One Belt One Road; the introduction of the biggest and fastest mobile telecommunications network in the world; and "Made in China 2025," an upgrade to 10 industries, including biomedicine, information technology and clean-energy generation.

But while Bannon yearns for a confrontation with China, others worry about potentially devastating effects on the American economy, citing research that a trade war could lead to millions of lost jobs and higher prices for consumers.

Trump was a protectionist long before he met Bannon. In the 1980s, he was a frequent critic of Japan, which was then in the midst of an economic expansion. "They come over here, they sell their cars, their VCRs," Trump complained to talk show host Oprah Winfrey in 1988. "They knock the hell out of our companies." In 2015, he launched his presidential campaign with a similar broadside against Japan, though this time without mention of VCRs. He described a national landscape resembling The Grapes of Wrath: "They can't get jobs, because there are no jobs, because China has our jobs and Mexico has our jobs."

Trump's campaign manager in the early days, when his bid for the Republican nomination seemed either a joke or a publicity bid, was Corey R. Lewandowski, who channeled Trump's pugnacity and bluster. Next came Paul J. Manafort, who piloted the campaign to Cleveland for the Republican National Convention. But by late summer, Lewandowski says, his "primary juggernaut" had been perverted by Manafort into a "general election failure." In his refreshingly punchy new book about the campaign, Let Trump Be Trump, co-authored by Bossie, Lewandowski has a newly hired Bannon watching, aghast, as Manafort gives a television interview from the Hamptons, dressed in boating attire. Manafort was gone within days.

The man who replaced him was little known to the kinds of people who make it their business to know everyone in Washington. He'd worked for Goldman Sachs, made some conservative documentaries in Hollywood and collected millions from having purchased a share of the Seinfeld television series back catalog. Now he was running Breitbart News, a potent force on the right still obscure to readers of The New York Times. A profile in Bloomberg Businessweek showed Bannon in shorts and untucked dress shirt, looking like a mildly disgruntled couch potato.

Bannon's elevation to campaign manager seemed to signal desperation, a reaction he recalls now with delight. "As soon as I took over, they said, 'Oh my God, Trump's going to lose by 25 points now, they brought in the mad bomber, just to destroy his enemies on the way down.'" He does not harp on the victory over Clinton quite as much as Trump does, but he has mentioned it in every speech I've heard him give: in California, Alabama, Washington. For him, it is a lesson that the moribund establishment can be defeated. And must be defeated.

Campaign alumni frequently follow their victorious candidate to the White House, but not since Karl Rove arrived at the West Wing with George W. Bush has an appointment been met with so much alarm—Bannon's new position would be chief political strategist, a press release several days after the election said. "Bannon will be the most powerful person in Trump's White House," wrote Ryan Lizza of The New Yorker.

So why didn't Bannon use that power to advocate more forcefully for his populist views? Miller, who ran communications for the Jeb Bush campaign and is now one of Trump's most vociferous Republican critics, believes those ideas were never more than an ideological Potemkin village for "cultural and racial grievance." He says Bannon's genius was in spotting the first shoots of that grievance in the wild ecosystem of right-wing internet news outlets.

Although Bannon reportedly sought a top tax rate "with a 4 in front of it," the notion of a tax increase was dismissed as whimsy, "a dead cat bounce," in the words of free-market activist Grover Norquist. Infrastructure Week, which the White House could have used to make the case for a Works Progress Administration–style plan, ended with a proposal to privatize air-traffic control. Nor did Bannon push for the kinds of smaller-scale solutions that both Republicans and Democrats could have supported: faster internet in rural communities, free community college, effective job-retraining programs, expansion of opioid-treatment programs. These would not have been revolutionary, but they would have likely been effective.

Bannon left the White House in mid-August, after clashing with national security adviser H.R. McMaster, chief economic adviser Gary D. Cohn and the president's influential daughter, Ivanka Trump. (Again, by no means a complete list.) At the time, he looked miserable, exhausted.

"I'm so happy since I've been out of the White House," he says now. "I'm just not built to be a staffer, right? In the White House, I had a lot of influence, but at the end of the day, you're a staffer. It's just a different thing. It's very hierarchical, you've got your lanes you gotta stay in. It's not the way I roll."

Bannon continues to regularly talk with the president. But while he said that he spoke to Trump for more than 30 minutes on the day of the Alabama special election, someone with access to the White House call logs said the call was only nine minutes long.

That discrepancy may be telling. A senior White House official, who could speak only on the condition that her name not be used, told me that the relationship between Trump and Bannon has "soured," even as media reports continue to paint Bannon as a Rasputin figure singularly capable of influencing the president. She dismissed any notion that Bannon would be advising the president on strategy for the 2018 elections. "We have no desire to engage with him in any way in '18 on campaigns or other topics," the official told Newsweek.

The White House official adds that Bannon's influence on China policy has been exaggerated: "People want to credit Steve for some of the language and the rhetoric, but these are things the president has been talking about for years."

As far as Bannon is concerned, no amount of palace intrigue can eclipse Trump's work on the economy. Asked if Trump were an economic nationalist, he says, "Look at his policies." He attributes Trump's success to the protectionism that animates them both, listing the executive orders that, he believes, are going to be accelerants to the American economy, the manufacturing sector in particular: "the 301 on intellectual property, the 201 on aluminum, the 232 on steel."

While he admits that the tax bill congressional Republicans just passed is flawed, he won't denounce it as a giveaway to corporations and billionaires, having apparently adopted the widespread conviction of congressional Republicans that getting anything passed—no matter how unpopular—is better than passing nothing.

"President Trump should be eligible for the Nobel Prize in economics," Bannon says. "He's proven that economic nationalism works. He's getting the animal spirits flowing in America."

The Right-Wing Liberal

Robert Kuttner was vacationing in Tanglewood, the bucolic classical music retreat in Lenox, Massachusetts, when he got an email from Bannon's assistant, inviting him to meet at the White House, where Bannon was then employed. Unable to travel to Washington, Kuttner agreed to a phone call. "Bannon promptly called," Kuttner wrote in an account of their exchange.

"I've followed your writing for years," Bannon told him. This stunned Kuttner, who edits The American Prospect, a progressive magazine consistently critical of Trump and the Republican Party. Nevertheless, Bannon recognized that Kuttner, like other progressives, shared his antipathy to free trade and militarism. Their many differences, especially on social issues, he appeared to ignore.

"We're at economic war with China," Bannon told Kuttner, in an interview that was astonishing for its incautious honesty. He promised to install China hawks at the State Department while admitting that there was "no military solution" to the standoff with an increasingly bellicose North Korea. Asked about the white nationalists who were purportedly his allies, and whom Trump had praised as "very fine people," Bannon dismissed them as "a collection of clowns."

Bannon was gone from the White House within two days. Even if he was already on his way out, the Kuttner interview was a middle finger thrust high into the air. It was also an intriguing reminder that there's some overlap between the far left and the far right, at least on economic views. The political extremes bend toward each other in their antipathy to the free-market capitalism of the flattened, digitized world. Twelve percent of people who voted for Vermont's Senator Bernie Sanders, a self-described democratic socialist, voted for Trump in the general election.

I spoke to a Democratic congressional staffer on Capitol Hill who was invited to the Breitbart Embassy because Bannon had learned of his work and was intrigued by the possibility of cooperation. The staffer, who asked that his name not be used, said he was "shocked" by Bannon's "interest and level of respect." They talked about populism and war. "His willingness to engage was striking. It was a surreal experience."

"It's obvious he could not last in the Trump administration, in part due to his opposition to wars of choice, hypermilitarism and endless U.S. occupations, and also some domestic policies where he sides more with liberal Democrats than with Republicans, including full employment, wage growth, fair trade, antitrust enforcement and serious spending on infrastructure," says the Democratic staffer, who fears being "crucified" by fellow liberals on the Hill for merely meeting with Bannon.

Bannon's understanding that class discontent would eclipse party affiliation in the 2016 election was prescient, and even his harshest critics concede that. Steve Schmidt, a top adviser on John McCain's 2008 presidential campaign, credits Bannon with seeing the shift to populism before many others did. But he calls Bannon's economic nationalism movement "an absurdity" that will ruin the Republican Party unless McConnell and Ryan beat him down before the 2018 midterms. "The revolution he speaks of is a freak show," Schmidt says of Bannon's movement. "The only thing missing is someone in a Chewbacca costume next to him on a stage."

Kuttner, too, is skeptical that Bannon can win converts from the left. "Hitler had a terrific interstate highway system," he says. "Hitler also had a terrific welfare state. But that doesn't mean progressives have anything in common with Hitler." He says this not to compare Bannon to Hitler but to caution that "incidental overlap" shouldn't be exaggerated into a bigger political confluence. Kuttner notes, like many others I spoke to, that Bannon has thus far failed to field a candidate who embraces his eclectic set of ideas. "Unless he's planning to run for office himself, he's mostly blowing smoke," Kuttner says.

Bannon is planning no such run. And yet he continues to flirt with ideas that could be more attractive to the center-left than the far right. He believes, for example, that Silicon Valley has become too powerful. "Google and Facebook ought to be public utilities. I think they're too big for control. And I think that data ought to be held in trust. These ought to be regulated like utilities. Like the gas works."

It's an intriguing idea, one that has been wafting through liberal outlets for some time. Of course, nothing will make that idea toxic to liberals quite like an endorsement by Bannon. Democrats can only hope he doesn't start preaching about a $15 an hour minimum wage.

The Fighter Still Remains

Political campaigns are like military ones, and not only for the lack of sleep. The losing faction resorts to blame and recrimination, while the winners embalm their victory in flawless amber. The House of Representatives could flip in 2018 and, under Democratic control, vote to impeach Trump. But those who fought for him in the months leading up to November 8, 2016, those happy few, will always have Wisconsin.

One cold night in December, Bannon threw a party for Lewandowski and Bossie, who'd just published Let Trump Be Trump, their brisk account of Trump's march to Washington. The party was held at a steakhouse across from the Fox News headquarters in midtown Manhattan. The place slowly filled with conservative luminaries, like Ann Coulter, who brushed off someone who wanted to snap her picture, and Sean Hannity, wearing a green field coat that made him look like a suburban dad. Loud and happy, Lewandowski bounded between guests. Cindy Adams, the gossip columnist, wore a white coat. An olive-oil importer told me about the proto-Trumpian culture warrior Patrick Buchanan and his collection of antique guns. I recall bacon, ample and delicious.

Bannon came near the end of the affair. When he did, the already crowded room imploded around him, as if a new gravitational field had formed. He was the star among stars. Bannon knew this, accentuating his import by dressing down for the occasion, wearing a barn coat and cargo pants, which both looked comfortable and entirely inappropriate in this room of tailored suits. True power is dressing exactly as you damn well please.

Bannon is unique among those who have left the Trump administration in that he has not attempted to trade on his association with the president for personal profit. Plenty of others have, even if their association was a lot more tenuous. Having vowed to continue fighting for Trump when he left the White House, Bannon has done just that. Losing a skirmish in Alabama is unlikely to temper his zeal. Bigger battles loom. "One of the things he does, that most of us in Washington don't do, is he thinks in terms of history," says Keith Koffler, the White House Dossier author who recently published a biography of Bannon, Bannon: Always the Rebel. "It will be very little of a deterrent to him at all, what happened in Alabama."

Several days after Moore's loss, pundits and columnists were still arguing whether Bannon was to blame, what the election meant for Democrats, what it meant for Republicans, what it meant for Americans and whether it would save democracy.

Bannon, meanwhile, went to Tokyo. There, he gave an address to a conservative group, praising Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe for being "Trump before Trump" by reviving Japan's long-dormant nationalist impulses. "Japan has every opportunity to seize its destiny," he said. But only if it stands with the United States against China.

Back home, Trump released a national security strategy that branded China a growing threat. "China expanded its power at the expense of the sovereignty of others," the document says. "Its nuclear arsenal is growing and diversifying. Part of China's military modernization and economic expansion is due to its access to the U.S. innovation economy, including America's world-class universities." If this wasn't written by Bannon, it was inflected with his ideas.

But almost as if to underscore how much Bannon's influence has diminished, the White House shortly thereafter appointed Susan A. Thornton its top East Asia diplomat. This was seen as another defeat for Bannon, who'd bragged to Kuttner that he'd have her expelled from the State Department.

So now it is winter, and Bannon is in the wilderness, tromping through the snow, preparing for numberless battles to come. He hears the crackling reports of incoming fire but doesn't bother to duck. "I think it's one of my superpowers that I don't care what people say. I really don't." For him, this is only the beginning of his movement, not the end: the first inning, not the ninth, as he put it to me in Montgomery, with stars falling over Alabama, Roy Moore demanding a recount, and reporters pecking away at their laptops, writing obituaries for Bannon and his revolution.

"We're fighting on tonight," Bannon said as aides came into his hotel room with gravid, greasy bags of Arby's. "We'll get up and fight tomorrow morning."

An earlier edition of this article incorrectly deemed Keith Koffler's biography of Bannon "authorized." It is not an authorized biography.