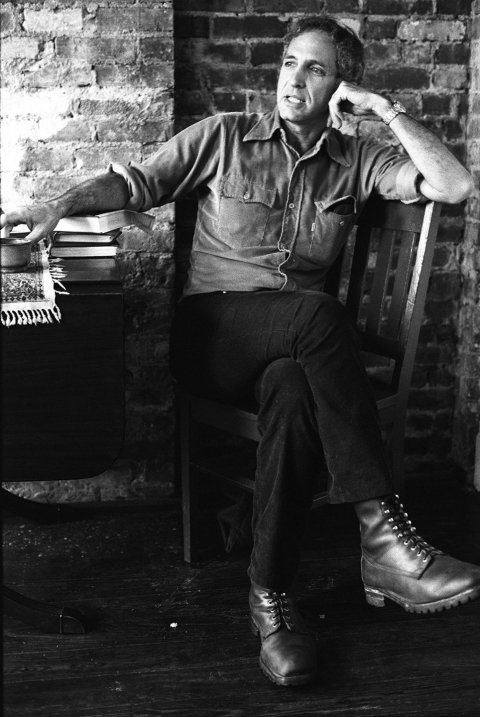

What motivated military analyst Daniel Ellsberg to risk a lifetime in prison by leaking the Pentagon Papers, a top-secret Defense Department history of U.S. deception in Vietnam? In the movie The Post, a contender for best picture at the Academy Awards, it was Ellsberg's disenchantment with the war, which flared after a 1966 flight back from Vietnam with Defense Secretary Robert McNamara. In quiet conversation with Ellsberg aboard the plane, McNamara had privately agreed that the war was a bloody stalemate, but he later told the press that the U.S. was making progress. However, another three years passed before Ellsberg made the momentous decision—and it was not McNamara's lie that festered until it became intolerable. It was something else entirely. In 1969, a Green Beret unit came to suspect that one of its top Vietnamese agents, a man named Thai Khac Chuyen, was secretly working for the Communists as a double agent. After failed efforts to extract a confession from him, despite days of interrogation with "truth serum" drugs, three of the soldiers took him out on a boat, weighed him down with chains and a tire rim, shot him in the head and dumped him overboard. The "termination with extreme prejudice" eventually leaked after Chuyen's wife began making inquiries at the U.S. Embassy about his whereabouts. Seven of the Green Berets, including their dashing commander, Colonel Robert Rheault, were arrested and charged with murder and a cover-up. It soon emerged that the defendants were going to present evidence that the CIA had approved the killing, and as the case headed to trial, the affair exploded into a national controversy. Then, suddenly, the Army dropped all charges.

The resolution of the case deeply disturbed Ellsberg, who saw it as a metaphor for all the lies and cover-ups of the Vietnam War.

The incident goes unmentioned in The Post, but in my 1992 book, A Murder in Wartime: The Untold Spy Story that Changed the Course of the Vietnam War, I described what finally triggered Ellsberg's decision on September 30, 1969. What follows is an edited excerpt.

A Not So Quiet American

Daniel Ellsberg lay in bed reading an account of the Green Beret case in the Los Angeles Times. Outside his window, the azure waters of the Pacific knuckled on the white sands of Malibu. As he read on, drinking his morning coffee, he began thinking how hard it would be to give all this up.

A wiry, intense intellectual with piercing blue eyes, Ellsberg was one of the few real American experts on Vietnam. He had made several trips to Saigon in the early 1960s as a State Department officer, studying counterinsurgency under Edward Lansdale, the legendary Air Force colonel and CIA operative fictionalized by Graham Greene in The Quiet American. A former Marine, Ellsberg often went off by himself into the villages to ask questions. Despite his growing doubts about the war, he wrote the doctrine on pacification for the U.S. Embassy. To his horror, a few years later, it formed the basis for the U.S. Phoenix program, which targeted suspected Communist agents for assassination.

In 1964, working for the Defense Department, Ellsberg had also become a recognized expert on the dynamics of force and negotiations. Threats of escalation, he concluded, never worked with the North Vietnamese. Instead, they had the paradoxical result of propelling the United States into an ever-deepening quagmire to maintain its credibility.

Ellsberg's skepticism about a satisfactory solution to the war expanded with every new brigade and squadron hurled into Vietnam. In 1965, he happened to be in Saigon when Henry Kissinger visited and asked the embassy for an off-the-record briefing by resident Vietnam experts. Ellsberg told the Harvard professor (and future Nixon administration foreign policy guru) that senior military officers had repeatedly misled McNamara, Lyndon Johnson's secretary of defense. Go talk to the younger men in the field, he urged Kissinger. Go without an embassy escort. Talk to the lieutenants and captains. Talk to some Vietnamese outside the system.

Kissinger came back deeply pessimistic about the chances for victory, believing that the Saigon government was not worthy of support. The U.S. negotiating strategy, he confided to friends, should be designed to create a "decent interval" between a U.S. withdrawal and an inevitable Communist takeover.

He was grateful to Ellsberg. "I have learned more from Dan Ellsberg," he told one group during a lecture, "than anyone else in Vietnam." A few years later, however, the invitation from President Richard Nixon to be his national security adviser prompted Kissinger to revise his views. He now thought more bombing could work.

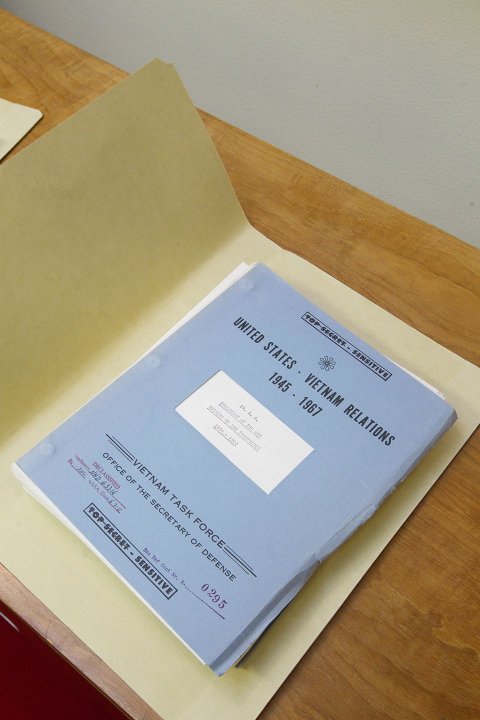

Ellsberg, meanwhile, had undertaken an unusual assignment. The Pentagon had put together a team of national security experts to compile a diplomatic, military and political history of the Vietnam War. He was invited to join.

The Pentagon vaults revealed a top-secret record in deep contradiction to the official versions of events. As Ellsberg waded into the boxes of classified cables, back-channel messages, embassy reports and CIA memorandums going back 25 years, he discovered that the U.S. had piled deception on deception all through its involvement in Indochina. The documents recounted the World War II–era requests of Ho Chi Minh, then an anti-colonial guerrilla leader, for a copy of the Declaration of Independence, and his plans to use it as a model for Vietnam. They recorded President Harry Truman's reneging on the wartime pledges of his predecessor, Franklin Roosevelt, to keep the French from reclaiming Laos, Vietnam and Cambodia as their colonies at war's end. From the spurious election of Ngo Dinh Diem as South Vietnam's president—and U.S. complicity in his 1963 assassination—through the secret CIA war in Laos, sabotage operations in North Vietnam and the implementation of the Phoenix Program, the Pentagon vaults disgorged an ugly, disturbing history of official deceit in Vietnam.

What particularly stunned Ellsberg, though, was the record of events surrounding a clash in the Gulf of Tonkin in 1964, an incident that provoked the U.S. bombing of North Vietnam and led to the introduction of the first U.S. ground combat units into the war. President Johnson's explanations for the incident were completely false, Ellsberg discovered. In the White House version, Communist patrol boats fired on innocent U.S. destroyers in international waters off North Vietnam. But in the top-secret files, Ellsberg learned the warships were encroaching on North Vietnamese waters in support of classified Green Beret sabotage missions in North Vietnam. Even the much-ballyhooed "attack" on the destroyers was doubtful; the captain of one of the ships had misinterpreted radar "shadows" as torpedoes; no other evidence of an attack existed. Johnson and the Pentagon had manipulated the incident to stampede Congress into passing an open-ended war resolution.

In Ellsberg's view, a tragedy of immense proportions followed. He was no stranger to lying, having served in high levels in the government, but this particular deception shocked and depressed him. The Tonkin Gulf lie was directly responsible, he believed, for 16,000 American deaths to date and hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese casualties, with more dying every day. (By war's end, there would be over 58,000 U.S. military service members and 1.3 million Vietnamese killed.) Had the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee known about the deception, he thought, Congress never would have granted Johnson carte blanche to wage war. And the American people would have known that Johnson's pledges of peace during his presidential campaign were a fraud. The Texas Democrat had been planning to escalate all along, just as Nixon and Kissinger were now, Ellsberg knew from his contacts in the White House. But the intense defense analyst found no one in Congress willing to believe him.

To Ellsberg, the threads of the Green Berets wove all through the secret history of the war, from early raiding parties in North Vietnam through the creation of "l'armée clandestine" in Laos, their curious background role in the Diem assassination and now the scandal surrounding Colonel Robert Rheault, commander of the Green Berets in Vietnam. As Ellsberg read through the long account of the case in the Los Angeles Times, his revulsion and anger grew. He concluded that the cover-up began at the bottom and moved up, from the three captains who carried out the murder to the major above them and then to Rheault. The colonel then lied about Chuyen's disappearance to General Creighton Abrams, the commander of U.S. forces in Vietnam, who then lied about the motives for his prosecution. And the grand finale was Army Secretary Stanley Resor's deception about why the case was dropped. Of course the CIA men could be compelled to testify, Ellsberg knew; all the president had to do was order them.

This is a system I've served for 15 years, he thought. It is a system that lies automatically, from top to bottom, to protect a cover-up of murder. His attention drifted to his copy of the secret history of the war—thousands of pages locked in a safe in his office.

'We Need a S.O.B.'

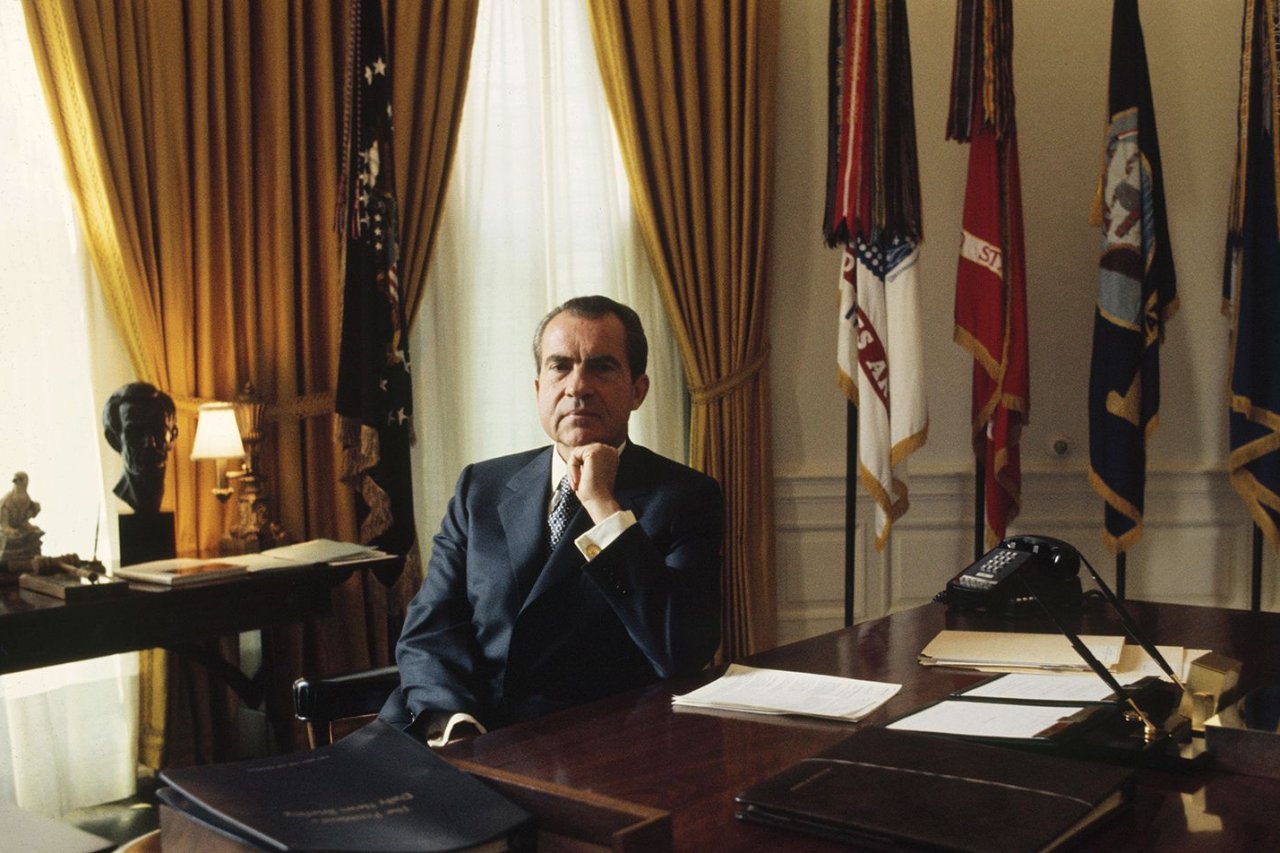

As Ellsberg brooded, Nixon sat down at his Oval Office desk and scratched out a handwritten note. After a mysterious delay, the House of Representatives had finally passed the military funding bill under the guidance of L. Mendel Rivers, the powerful chairman of the Armed Service Committee. Rivers had also helped keep the Green Beret affair quiet while the case was under investigation. The president was grateful.

Dear Mendel,

I need not emphasize the importance to our country of issues involved. You know them as well as I do, and you acted as you always do where the good of the nation is at stake.

Thank you,

Richard M. Nixon

Nixon had handled the Green Beret case just as Ellsberg suspected. And for good reason, the president believed: to protect national security secrets, particularly relating to Cambodia.

Every president who had dealt with the war thought he had acted reasonably. Nixon had come into office, as had his predecessors, determined to project the view that the war was winnable without great domestic sacrifice. Each had been forced to discard bits and pieces of his strategy along the way while maintaining an aura of normalcy. Unable to provide a satisfactory explanation for the mounting American commitment, Nixon, like Johnson and John F. Kennedy before him, had been forced to rely more and more on secrecy.

Nixon had vowed not to be consumed, as they had, by Vietnam. He had much wider concerns: arms-control agreements with Moscow, an overture to China, the unity of Europe, peace in the Middle East, a welfare overhaul, crime.

To establishment liberals, Nixon's campaign message had been comforting. The war was going to end, the agony of a long conflict brought to a close. There would be peace in the streets. "Greatest Generation" parents could talk to their disillusioned children. Students would go to class. Draft resisters could return from Canada. Everyone could go back to normal.

The image of impending tranquility was intended to translate differently in Hanoi, however. With the war only one item on the administration's agenda, and with the American public opinion under control, Nixon would be free to carry on the fight on his own terms. That's what the Nixon men wanted Ho Chi Minh to know.

Then came the Green Beret case. It was a piddling matter, considering the wholesale carnage the U.S. was inflicting on South Vietnam. But the letters had come pouring in, threatening to reignite a debate on the morality of the war, the conduct of troops, the methods of counterinsurgency and the wide range of activities pointing toward an American invasion of Cambodia. The Green Beret case threatened to make the war his. In late September, Nixon had feigned disinterest in Vietnam. There were long days at Camp David and sailing in the Sequoia. He played golf at Burning Tree with Bob Hope. He hosted Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir at a glittering White House dinner. But beneath the projected calm, the president was as consumed by Vietnam as his predecessor was.

On the morning of September 25, 1969, the president convened a breakfast meeting with all of his top generals. The basement meeting was officially characterized as routine. On the docket, however, were top-secret plans to invade Cambodia and Laos, resume the bombing of North Vietnam and mine its Haiphong Harbor. But as the president was beginning to learn, the Green Beret defendants were conducting related research in Saigon; copies of lawyer's subpoenas for the testimony of CIA Director Richard Helms, Defense Secretary Melvin Laird and Army Secretary Resor, relating to years of illegal operations in Indochina, were arriving daily at the White House. So were defense petitions asking the president to intervene and dismiss the charges. And then came the not-so-oblique call from Chairman Rivers telling him to squash the case.

Nixon had promised to do something about it but curiously hadn't. Was he still trying to burn Helms with the CIA's involvement in the Green Beret affair? Bob Haldeman, Nixon's chief of staff, suspected that was true. But by the end of the week, he knew he had to force his boss to pay attention to the case. He made a note to himself, "Green Beret-Mon." They had to get rid of it.

The president seemed less interested in the Green Berets than college students who had just returned to campus looking to escalate their anti-war protests. In April, over 300 anti-war protesters had invaded Harvard's University Hall, chased out several deans and staffers, and occupied the building until a bloody police raid evicted them. Over the past year, increasingly combative anti-military campus protests had ended in the closure of some 40 college and university ROTC (Reserve Officers Training Courses) programs. As the "Chicago Seven" trial of protesters at the 1968 Democratic National Convention began,, Mark Rudd, a leader of the militant Weather Underground, vowed, "The violence is just beginning."

A major Nixon worry was a march on Washington scheduled for October 15. White House aide Charlie McWhorter was dispatched to meet secretly with its organizers, Sam Brown and David Hawke. He reported back that the protests would be big and cautioned the White House not to antagonize the anti-war movement with more inflammatory statements.

Nixon brushed the advice aside. "It's absolutely essential that we react insurmountably and powerfully to his blunt attack," he instructed Haldeman in a lengthy memo. Nixon proposed that his speechwriter Pat Buchanan mount a phony letter-writing campaign against Massachusetts Senator Ted Kennedy, who had recently charged that the slow pace of troop withdrawals and negotiations was cover for more escalation.

But Nixon wanted to hit the anti-war forces harder. On the morning of September 28, as lawyers for the Army and CIA worked out the final details in the Green Beret prosecution, Nixon told Haldeman to hire Charles Colson, a White House staffer assigned to deal with special interest groups, to help discredit liberals. "One of the best follow-up men," Haldeman wrote in his notes on the meeting. "Dirty tricks. Take him out of his job—onto the attack. He's competitive, restless, not a grey p.r. type. We need a S.O.B."

Colson, a conservative New Englander, shared Nixon's visceral hatred for the Kennedys. He had a former CIA man, Howard Hunt, dispatched to Martha's Vineyard to see if he could dig up any more dirt on the accident at Chappaquiddick, where Ted Kennedy drove off a bridge and left a female staffer to drown in his car. In Washington, Hunt began quiet research on the Kennedy administration's involvement in the overthrow of South Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem and recommended they fabricate diplomatic cables tying Kennedy personally to Diem's assassination.

Nixon was finally forced to focus on the Green Beret case during the daily 9 a.m. staff meeting on September 29. The morning network news shows had been filled with film of the civilian lawyers and the press pouring into Saigon for what was being billed as the "biggest show trial of the decade."

It was time to get rid of the case, Nixon said, sitting at his desk in the Oval Office. Helms had been rattled enough by leaks pointing to CIA involvement in the Green Beret case. Haldeman and presidential assistant John Ehrlichman listened. There had been rumors that the CIA chief had used Attorney General John Mitchell to lobby Nixon to intervene in the case. The agency wouldn't be worth a damn in Vietnam, Helms had allegedly said, if the case went forward. But after weeks of lurid publicity about CIA assassinations, it wouldn't be easy to make it disappear.

The president and his staff considered alternatives. Haldeman suggested using Egil Krogh, a lawyer on Ehrlichman's staff responsible for Hunt, and Gordon Liddy, a former FBI agent who would do anything to help Nixon. Krogh was trustworthy; he had been helping Colson with dirty tricks against officials suspected of disloyalty to the president.

Kissinger's people would have been involved too, Haldeman scribbled in his notes. "Get a letter from the CIA saying they will refuse to provide witnesses for the Green Beret trial—executive privilege." The details could be worked out with CIA counsel Larry Houston. "Without CIA witnesses," Nixon declared, playing the lawyer, "the rights of defendants will be prejudiced."

No witnesses, no trial. Creighton Abrams? Tough. We can't sink the whole ship because the general hates the Green Berets. Let him take out his rage some other way. Resor? Let him get the messages from the CIA. What can he do? He'll have no other choice but to go along.

That would end it, Nixon thought. And there would be no White House fingerprints.

The Biggest Leak of Them All

On the morning of September 30, Ellsberg read Resor's explanation for dropping the charges. The CIA was not going to provide any witnesses who could back up the claims of the Green Beret defendants that two of the spy agency's men had advised them to "get rid of" Chuyen, the Vietnamese agent suspected of treachery. Faced with that, Resor said, "the defendants cannot receive a fair trial. Accordingly, I have directed today that all charges be dismissed immediately."

Ellsberg put his newspaper aside. His thoughts again went to those top-secret documents in his safe. If he leaked them, he knew his whole life would change. He'd certainly go to jail for many years; his security agreement was quite specific about that. He'd no longer have the rambling house on the Pacific Coast Highway. After that, who knew? He'd no longer be employable as a government consultant, and who else was interested in his arcane skills?

But another vision of devastation, less personal, came into his mind: thousands of dead and maimed American soldiers for years to come. A million dead Vietnamese, Laotians and Cambodians. Villages in flames, peasants wailing. It was a trail of carnage that stretched over and beyond the horizons of his imagination.

The lying had to stop. The murder of Chuyen was just one more death, but it was one too many.

The documents in his safe were the solution to a mass murder mystery, Ellsberg thought. They explained why 2 million Vietnamese had died on America's Cold War chessboard. They explained how four American presidents had secretly, and fruitlessly, escalated their war before Nixon was elected. Now, a new chapter in the history of crime was about to be opened.

Only if Congress and the American people saw the secret documents themselves would they be persuaded to believe what Ellsberg knew: that Nixon and Kissinger were planning another escalation while professing peace. That they would be bombing Cambodia despite the forceful and successful denials by the White House six months earlier. That the United States has been mucking around in Laos and Cambodia for a long, long time. That the United States had been running death squads under the cover of a police program called Phoenix.

If Congress understood the past, Ellsberg thought, it might be persuaded to consider the bloody future.

Ellsberg called Anthony Russo, a colleague at the Rand think tank in Santa Monica. Russo had worked on the secret history project, and like Ellsberg, he had once been a Pentagon consultant and Vietnam believer.

"Do you know where there's a good photo copying machine?" Ellsberg asked. Russo did, and he was ready to go. He could start copying the papers that night, he said.

"Let's do it," Ellsberg said.

How wonderfully ironic, Ellsberg thought as he hung up, that Nixon thought he could keep all of the secrets bottled up forever.

Not this time, Ellsberg vowed. Not this murder. Nixon had just triggered the biggest leak of them all, the whole secret, sordid history.

The Pentagon Papers were on their way.