Updated | "Hail Trump!" Richard Spencer bellowed. "Hail our people! Hail victory!"

It was November 2016, not long after Donald Trump's surprising presidential victory, and Spencer, perhaps America's most well-known figure in the so-called alt-right, was speaking to a packed room of white nationalists in Washington, D.C. A clip of the speech, first published by The Atlantic, went viral and seemed to confirm the worst fears of many Trump critics: that the president-elect had empowered a fringe movement of racist, right-wing radicals and launched it into the mainstream.

But less than 18 months later, on March 5, 2018, Spencer spoke in front of another room of like-minded supporters, this time at Michigan State University. Only now, the audience was smaller than the one in D.C., and Spencer seemed far less triumphant. "We are going to have to suffer through these birth pangs of becoming a real movement," Spencer said, referring to the scattered crowd. Outside, a smattering of self-identified neo-Nazis rumbled with a much larger group of left-leaning protesters.

What was perhaps most striking about Spencer's event in East Lansing, however, was who didn't show. Kyle Bristow, Spencer's attorney, who helped him secure the speaking engagement, wasn't there. He had publicly quit the movement days earlier. Also notably absent: Mike Peinovich, a podcaster and Spencer ally who frequently talks about Jewish conspiracy theories. Another Spencer ally, Elliott Kline, wasn't there either. (Kline did not respond a request for comment.) He hasn't made a public appearance since February, when a story in The New York Times appeared to show he had been untruthful about his service in the Iraq War. Even the Daily Stormer, a neo-Nazi website that was critical in promoting past Spencer speeches, declined to cover it; instead, its home page featured a story ridiculing the Oscars.

More than a year after Trump's victory, the alt-right movement may be floundering, falling well short of its ambition to achieve mainstream acceptance. The coalition, which once seemed so formidable, now appears divided by infighting, while its online presence has dwindled because of Twitter and other media platforms purging its most influential accounts for producing offensive content. Meanwhile, some analysts say the movement's violent encounters with left-leaning protesters have come to overshadow most of what the alt-right hoped to achieve when Trump took power.

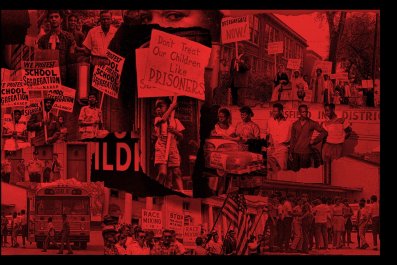

Things looked very different last August. At the "Unite the Right" rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, more than a thousand white men converged to protest the removal of a statue honoring Confederate General Robert E. Lee. Counterprotesters showed up, and the two sides clashed. In the process, James Fields, a 20-year-old Ohio native with far-right views, allegedly killed Heather Heyer, a protester, when he rammed into a crowd of people with his car. Most of the mainstream press was appalled, and Charlottesville Mayor Mike Signer called it a festival celebrating "the absolute worst elements" of society in a conversation with CBS's Face the Nation.

Trump took a different approach. "You had a group on one side who was bad, and you had a group on the other side that was also very violent," Trump said of the rally. Later, he added: "You [also] have people who are very fine people on both sides."

Since the deadly rally, most Republicans in office have tried to distance themselves from the alt-right. And by the time Spencer visited Michigan State, the group had experienced a series of setbacks. First, there was his speaking engagement at the University of Florida in October 2017, where police charged three of his supporters with attempted homicide after one fired a gun in the direction of a crowd. Then there was the White Lives Matter event in Tennessee later that month, where a crowd of neo-Nazis and white nationalists were outnumbered two to one by counter demonstrators, spurring a debate in the movement about how the alt-right should present itself.

And then there was the fallout over the death of Kate Steinle, a 32-year-old white woman from California. An undocumented Mexican immigrant named Jose Ines Garcia Zarate was acquitted of murder in her death, and about 20 neo-Nazis and white nationalists, many of them present in Charlottesville, rallied in front of the White House in December to express their anger over the verdict. Spencer, Peinovich and other alt-right figures gave speeches. It should have been a big moment for the movement, analysts say, especially since Trump had mentioned the Steinle case on the campaign trail. But a diverse group of anti-fascist protesters shouted down the small cluster of white men, and D.C. police escorted them away after less than half an hour. Media coverage was practically nonexistent.

Critics point out that the alt-right isn't a new movement, just a rebranded version of different hate groups that have been mired in division for decades. So the unified front America saw on display in Charlottesville is an anomaly. "It's historically typical to have fracturing in white supremacist movements," says Carla Hill of the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), an organization that monitors hate groups. "It makes you wonder about the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, if they were ever really united in the first place."

Anti-fascist, or antifa, activists, meanwhile, argue they deserve credit for the recent failure of alt-right events. Mark Bray, an activist and academic who is the author of Antifa, The Anti-Fascist Handbook, says the end of Trump's first year left him feeling "optimistic" that white supremacists could no longer organize effectively in public. He says Charlottesville and the lackluster rallies that followed showed that these events inevitably lead to arrests, backlash and infighting. "I'm cautiously optimistic," he adds, "that maybe we won't need to be talking about 'antifa' in the near future."

Liberals and even some of those on the far left have been critical of antifa's tactics. The writer Noam Chomsky called them "a major gift to the right, including the militant right, who are exuberant," suggesting that they embolden far-right recruiting and give government agencies an excuse to crack down on left-leaning activists.

But some key figures on the radical right say their opponents have hurt their movement. "The antifa have...pretty much succeeded in achieving what [mainstream liberals] cannot," Matt Parrott, a co-founder of the neo-Nazi group Traditionalist Worker Party, who resigned from leadership duties in mid-March, wrote on a popular alt-right forum following Spencer's event. "They demoralized and disabled the majority of the alt-right, driving them off the streets and public-square."

Even Spencer said as much after his talk at Michigan State, claiming that antifa is "winning." He posted a video overnight on March 11 in which he acknowledged that pushback from university administrators and antifa had made it difficult for him to continue to try to speak at colleges as he had planned. He said that the situation had forced him to reconsider his approach to movement building altogether. "The fact is, things are difficult," he said.

Yet the alt-right seems loath to admit its own actions and rhetoric may be driving away recruits, some observers say. In December, Christopher Cantwell, who is currently under house arrest in Virginia on felony charges for allegedly using tear gas and pepper spray at the Charlottesville rally, hosted Andrew Auernheimer on his podcast, Radical Agenda. Roughly 40 minutes into their conversation, Auernheimer, the man tasked with handling the technical side of the Daily Stormer, seemed to call for the murder of Jewish people in retaliation for his website being taken offline after Charlottesville. The rant even appeared to shock Cantwell. "Someone has to step in," Auernheimer said, referring to the Jewish elites he believes have collaborated to censor his right to free speech. (He declined to comment for this article.) "If you don't let us dissent peacefully, then our only option is to murder you. To kill your children. To kill your whole families."

It's not just talk. Violent incidents involving those with alt-right ties are on the rise. Earlier this year, the ADL announced that 2017 was the fifth-deadliest year for extremist violence since 1970, and that right-wing extremism accounted for 59 percent of the homicides that took place. Islamist militants, by comparison, accounted for 26 percent of the deaths.

The violence seems to have flustered alt-right leaders who have made a priority of trying to recruit law-abiding white conservatives into the movement. Brad Griffin, a vocal member of the movement, recently condemned both Auernheimer and his past praise of the neo-Nazi group Atomwaffen Division on a public internet forum. He accused them of making him and others look dangerous, and attracting the interest of federal agents.

Kit O'Connell, a Texas-based writer and anti-fascist activist, is concerned about what he calls a "cornered rat" phenomenon taking shape—one in which recruits of the alt-right give up hope of trying to build a lasting political movement and, as an alternative, simply lash out with violence.

Cornered or not, the alt-right's dream of an authoritarian white utopia is still alive. Identity Evropa, a white nationalist group that marched on Charlottesville, quietly drew three times the crowd that Spencer did at Michigan State at a conference in Nashville, Tennessee, on March 10. That group has been aggressively targeting college campuses, where white supremacist recruitment is surging, researchers note.

Still, as Spencer acknowledged in his March 11 video: "We're now in something that feels a lot more like a hard struggle. And victories aren't easy to come by."

Correction: A previous version of this story stated that that right-wing extremism accounted for 71 percent of extremist-related homicides that took place in 2017, according to the ADL. Right wing extremists accounted for 59 percent of the extremist-related homicides that took place that year.