Updated | In the late summer of 1969, the CIA director urgently sought a meeting at the White House. Richard Helms was determined to get President Richard Nixon to quash an Army investigation into the murder of a Green Beret informant in Vietnam. The case threatened to expose not just the CIA's assassinations program in that country, he argued, but some of the agency's more discreet killing devices, including lethal drugs.

Nixon despised the urbane, New England–educated Helms—and the CIA as a whole, which he considered part of the fashionable Georgetown crowd that looked down on him. But after letting Helms stew over his decision for a few weeks, Nixon forced the Army to drop the case, which indeed represented a Pandora's box of CIA dirty deeds. The assassinations issue went away until Congress caught up with it again after a series of news media reports and hearings beginning in 1971. Helms was tainted by the scandal but escaped town with an ambassadorship to Iran, leaving his successor, William Colby, the last CIA director to come from the clandestine service, to take the fall in widely televised hearings.

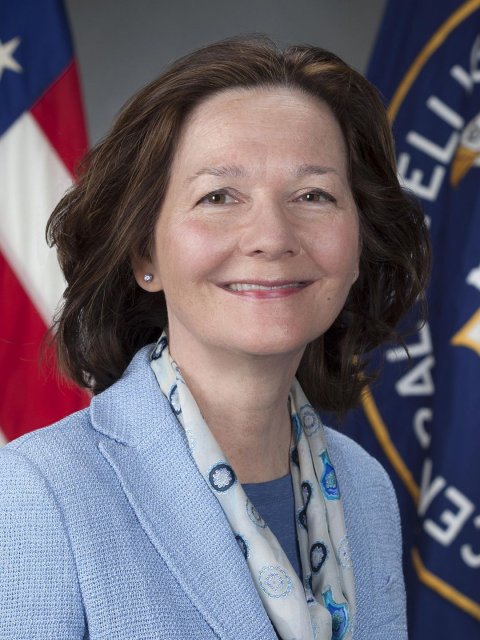

Gina Haspel, the Trump administration's 61-year-old nominee to run the CIA—and the first woman nominated for the job—faces similar circumstances today. Her hand in the CIA's program of "enhanced interrogations" of Al-Qaeda suspects might well have remained obscure had it not been for an attempt by former CIA Director John Brennan to appoint her to head of operations in 2013, just as the torture issue was coming to a boil with the Senate Intelligence Committee's inquiry into the agency's renditions, detentions and interrogation practices.

Additional revelations of Haspel's leading role in managing a torture site in Thailand and carrying out her boss's order to destroy the interrogation videotapes further soiled Haspel's reputation as an astute manager. But while the program had many authors—the George W. Bush White House, its Justice Department and CIA, not to mention congressional overseers—Haspel has the distinction of being the lone official to be summoned to Congress for a public reckoning for her actions.

"I have a lot of admiration for her," says a friend, who demanded complete anonymity because the nomination remains so fraught. "I think she genuinely learned her lesson" about following dubious orders. Haspel understands, the friend says, that waterboarding and other assaults on the prisoners were "morally reprehensible, if legal at the time. She recognizes it and is never going to go down that path again."

"She's very candid," West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin, a Democrat, recently told BuzzFeed News. "She does not believe the CIA should be in the interrogation business."

In the torrent of accolades that journalists and Congress have heard since Haspel's nomination was announced February 1, the spy agency makes no apologies for Thailand. One former CIA official, speaking on terms of anonymity to The New Yorker, said the appointment amounted to "the agency giving the finger to anyone who was ever critical of the program." But as former CIA Director Michael Hayden told Newsweek in March, her nomination was "clear evidence that the agency intended to neither repeat nor repudiate its past."

Leading Democrats on the Senate Intelligence Committee, and even some Republicans, like Susan Collins of Maine, want to hear Haspel explain, if not entirely recant, her past in public; they complain that the CIA has declassified only materials that make her look good. "Of course, what they really want to do is grandstand," said retired senior CIA operations officer Steven Hall. "It's duplicitous and disingenuous to say, 'We don't have access to that information'—any member of the oversight committee can ask for her personnel file, and they would get it, because that's a legitimate oversight responsibility. They just can't use it in public, which is what they really want to do."

What they are likely to hear is what the CIA and Haspel's backers have already said: that she was following legal orders, legalized by the Bush Justice Department, in her administration of the agency's counterterrorist interrogation program. But that won't satisfy her critics. They will want her to explain why she went along with the order of her boss, Jose Rodriguez, to destroy videotapes of torture she oversaw at a black site in Thailand.

Ali Soufan, the famed former FBI counterterrorism agent who discredited CIA claims that its torture produced valuable intelligence, said it was "reasonable" to ask Haspel about such claims. "Does she stand behind the attempts to mislead the public as to the techniques' effectiveness?" he asked in a recent Atlantic essay. "Does she stand by Rodriguez's public justification, that he was protecting the lives of his operatives, or his private one, documented in declassified emails, that the tapes would make him and his group 'look terrible'? Above all, if the torture program was so valuable and necessary, why destroy the tapes at all?"

Haspel may well pay the ultimate political price, her nomination shredded, largely because of the CIA's refusal to declassify more documents related to the interrogations. She's not likely to violate the spy agency's code of omertà in open session, said those who have worked with her. In that, she is much like Helms, who became known as "the man who kept the secrets," after the title of journalist Thomas Powers's authoritative biography.

"She is the woman who keeps the secrets," Daniel Hoffman, another former senior CIA officer, told Newsweek. "That's her. She's the most discreet person I ever worked with." Early on, when she signed up in 1985, she chose the clandestine world over a more public life with a husband and children, her colleagues said. Hall recalled asking Haspel what her weekend plans were as a meeting broke up one afternoon. "Steve, come on," he remembered her saying. "You know that I have no social life. I have no life whatsoever outside of work."

In Langley's executive suites, Hall continued, she had a reputation for "discretion on dicey personnel matters; discretion on operations, sensitive ones. She's extraordinarily discreet." And that likely includes limiting what she has disclosed to senators during her prehearing rounds on Capitol Hill, her former colleagues said.

But Haspel has made a point of finding allies on the Hill, said her friend. "Gina has gone out of her way as deputy director, before her nomination came up, to create dialogue among women members of Congress and women at the CIA, to talk about what she did in the past," the friend said. "So we'll see what comes of it. But I would far rather see her as CIA director than John Bolton and others who invaded Iraq and made torture legal. They've never been held responsible, but the woman in the room has."

Whatever Haspel's blemishes, many former CIA officers see her nomination as a bulwark against candidates they consider far worse, such as Republican Senator Tom Cotton of Arkansas, a waterboarding fan who was rumored last fall to be in line for the job. And he may be yet again if Trump, who has frequently disparaged the agency, tires of Haspel, a symbol of the CIA establishment.

"She's just going to be a placeholder" until the end of Trump's first term, at best, said a veteran of the agency's clandestine services. "If he decides that the Senate is secure" for Republicans after the midterm elections, the source told Newsweek, Trump "may well decide to move Tom Cotton there."

That prospect alone may spook Haspel's critics into voting for her. But even if her nomination fails, it isn't likely that a Senate panel with qualms over her record would approve someone of Cotton's ilk.

Hovering over all of this, of course, is the specter of Senator John McCain, ailing with terminal brain cancer back home in Arizona. While Richard Helms was keeping the secrets on Capitol Hill, McCain was in his second year of torture at the hands of his North Vietnamese captors in Hanoi—a fate Trump crudely mocked during his 2016 campaign. McCain's forthcoming book, The Restless Wave, makes no mention of Haspel, but in March he condemned her nomination, saying she was involved in "one of darkest chapters in American history."

McCain's opposition may shame other Republicans into rejecting Haspel. The Senate could then send her back to Langley to resume her career in a kind of shadow-world purgatory as the CIA's acting director until the president—or, more likely, his successor—comes up with someone better.

Correction: An earlier version of this story mistakenly described Richard Helms as the last CIA director to come from the clandestine service. William Colby was the last CIA director to come from the clandestine service.