On the evening of February 1, Tina Adams peered out the window of her hotel room in Charleston, West Virginia. It had been snowing for hours, and the roads were freezing over. Earlier in the day, she had driven two hours north from coal country to set the stage for a protest at the state Capitol.

Adams, a middle school teacher and mother of six, was furious. After 15 years at Baileysville Elementary and Middle School, in Brenton, she made about $47,000 a year—$12,000 less than the national average. Like many of her fellow teachers, she sometimes worked nights and weekends to boost her income; for extra pay, she offered private tutoring for students who had discipline problems or developmental disabilities.

It wasn't always enough, and Adams had begun thinking about selling her beloved Harley-Davidson Sportster to help her daughter buy a car. It was not the kind of life she envisioned when she launched her teaching career. And now, the state's governor, Jim Justice, was reneging on a long-promised pay raise and hiking health insurance premiums. Officials even wanted teachers to download a smartphone app to track their daily steps or face a financial penalty. As the president of her local union, Adams pushed for a walkout. "It's like all of us teachers had been pushed to the side and forgotten about," she tells me. "We finally reached a point where we were fed up."

And yet, as the snow fell in Charleston that night, Adams worried. She had organized her school's field trips and class dances—nothing like this. What if no one showed up? Her home in the southern part of the state had been an old union stronghold, yet West Virginia was now Trump country. Teachers hadn't taken any kind of major labor action in 30 years.

But the next day, Adams watched as a caravan of school buses rolled into the Capitol parking lot, horns honking. State snow plow drivers, supportive of the teachers' cause, had gone out of their way to clear a path on the interstate. Together, hundreds of educators from four counties filed into the statehouse to demand better pay and benefits. Their chants of "We're not gonna take it!" bounced around the cavernous rotunda. The one-day walkout—dubbed "Fed-Up Friday"—garnered local headlines. Lawmakers, however, barely shrugged; the Republican-led Legislature debated a bill that would give educators a minimal pay raise, but many grumbled the state didn't have enough money to cover it.

The message of Adams and her fellow demonstrators might not have reached Washington, but the protest had a profound effect on West Virginia. Teachers from around the state had watched a live stream of the protest while they prepared their lesson plans, and three weeks later, they joined in. For nine days, every public school in West Virginia shut down, as thousands of teachers from all 55 counties decamped to Charleston, the longest strike in the state's history. Amid a sea of red T-shirts, one homemade sign in particular seemed to capture their message: "Empty promises, empty schools."

Before long, the uprising became a movement. Within weeks, educators in Oklahoma and Kentucky walked out. Arizona quickly followed. It was a stunning development. All were Republican-dominated states with weak unions; as a result, ordinary teachers organized many of the demonstrations on Facebook.

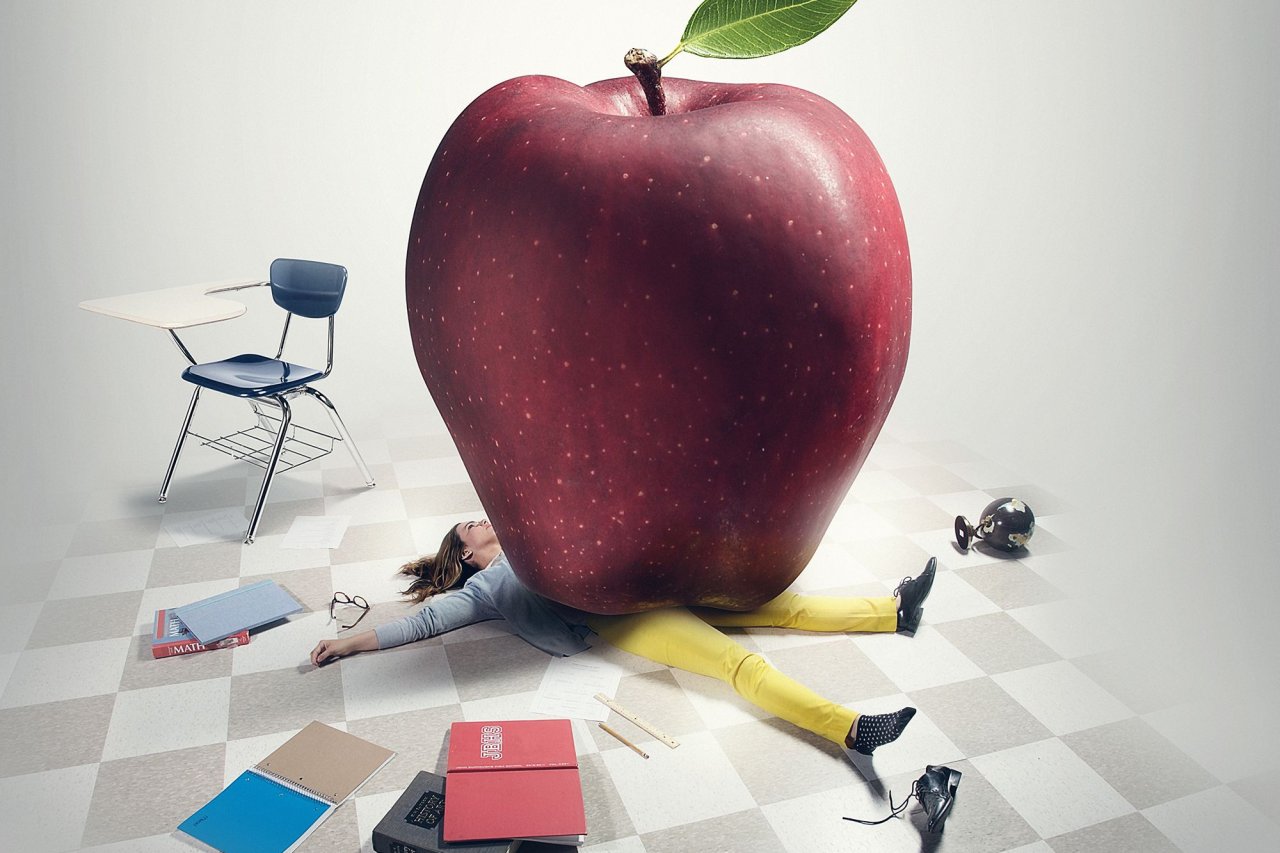

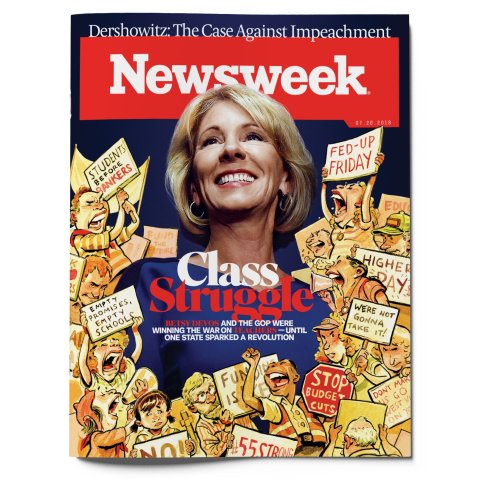

Sensing a potent political threat, the establishment pushed back, villainizing the educators. Oklahoma Governor Mary Fallin compared the striking teachers in her state to "a teenage kid that wants a better car." U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos urged them to return to work. "I hope that adults would keep adult disagreements and disputes in a separate place," she said, "and serve the students that are there to be served."

Kentucky Governor Matt Bevin went even further: The walkouts, he said, had directly endangered kids. "I guarantee you, somewhere in Kentucky today, a child was sexually assaulted that was left at home because there was nobody there to watch them," he told reporters. "I'm offended that people so cavalierly, and so flippantly, disregarded what's truly best for children."

It was the kind of incendiary talk that politicians—mostly Republicans—have used over the past two decades to curb organized labor and overhaul public education. But this time, to their surprise, it backfired. As the walkouts raged on, public support for the teachers swelled. In mid-April, an NPR/Ipsos poll found that three-quarters of Americans believed that educators had the right to strike—including two-thirds of Republicans. Just one in four said teachers were paid fairly.

In perhaps the most dramatic course correction, the GOP-led Kentucky House officially condemned Bevin for his remarks, then overrode his veto of a state appropriations bill boosting classroom spending. Teachers, one Republican resolution said, "are dedicated servants to our children who are deserving of our utmost respect and devotion." Bevin quickly apologized. The Republican policymakers in the other states ultimately granted much of the teachers' demands, from increased classroom funding to sizable pay raises.

On the surface, the teachers' success appeared to be a tectonic shift in the political landscape; suddenly, educators, long vilified in the public education debate, were heroes. But the cascading strikes across red America also represented something much deeper: the near unraveling of the modern middle class. If teachers couldn't hack it, who could? And if they failed, wouldn't we all fail?

Education is now one of the most pressing issues of the upcoming midterm elections, and both parties are rushing to embrace teachers, particularly in states like West Virginia, host to a number of competitive House and Senate races that could help determine control of Congress this November. Across the country, dozens of former and current educators are running for state legislative seats—34 in Kentucky alone—and giving Democrats hope in some of the most conservative corners in the nation. And labor unions, reeling from a recent Supreme Court decision that will likely drain their war chests and thin their ranks, are studying the teachers movement for lessons on how to maintain political power in hostile territory.

"I have been an educator since 1984, and this is one of the most exciting times of my professional career," says Jim Testerman, senior director of the Center for Organizing at the National Education Association (NEA), the country's largest teachers union. "Teachers have caught a glimpse of what is possible, and I don't think they are going back."

Deep Cuts, Falling Pay

Teaching was never a way to get rich, but it was long considered a solid and respectable middle-class occupation. Over the past few decades, though, policymakers have chipped away at the economic and moral status of educators.

The Reagan administration laid the groundwork with its seminal 1983 report "A Nation at Risk," which concluded the country's schools were "being eroded by a rising tide of mediocrity that threatens our very future as a Nation and a people." Among its recommendations: "more rigorous and measurable standards" for students and an "effective evaluation system" for teachers. Self-described reformers like President George W. Bush saw the document as a blueprint and pushed through new policies that focused on standardized testing and teacher accountability, first in state legislatures and then Congress.

President Barack Obama, a Democrat, picked up the mantle, repeatedly declaring that the country must "stop making excuses for bad teachers." DeVos, a Michigan billionaire who was a prominent charter school advocate before becoming education secretary last year, took the narrative to a dark conclusion: Public schools were a "dead end," staffed with teachers who "care more about a system [of unionization] than they care about individual students."

As lawmakers embraced more and more privatization—for example, voucher programs that allowed parents to spend public school dollars on private education—the Great Recession ravaged state coffers, depriving schools of even more support. States cut K-12 education deeply to balance their budgets, and districts laid off hundreds of thousands of employees. Most haven't bounced back. According to an analysis by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a left-leaning think tank, 29 states were spending less per student in 2015 than they were in 2008; in more than half of those states, the cut was 10 percent or more.

That has translated into larger class sizes and fewer resources for teachers. At the same time, educators' salaries remained flat or sank, devoured by inflation. In 39 states, the average teacher made less in 2016 than in 2010 after adjusting for inflation, an Axios analysis of federal data found. Meanwhile, the pay gap between educators and their non-teaching, college-educated peers is widening. In 1994, teachers earned about 2 percent less than comparably qualified workers in the private sector. By 2015, the "teacher pay penalty" had grown to 17 percent, according to the left-of-center Economic Policy Institute.

"It used to be a good job, with a reliable pension, health care and good wages," says Secky Fascione, a former NEA organizing director. "Not anymore. It used to be a profession, but now it's more of a service job."

An annual MetLife teachers poll found educators' job satisfaction dropped from 62 to 39 percent between 2008 and 2012, the last year teachers were surveyed. Unsurprisingly, many are dropping out of the profession. Between 2009 and 2014, teacher enrollment nationwide dropped from 691,000 to 451,000, a 35 percent reduction, according to the nonprofit Learning Policy Institute. Nearly 8 percent of educators leave the workforce each year, the majority of them before retirement age. Meanwhile, the student population is booming.

'One Big Family'

In West Virginia, Adams was feeling the pressure. On one hand, she loved her job teaching reading and math. She grew up amid the forested hills of the Mountain State, attended Baileysville Elementary and Middle School as a child and lived just a half-mile down the road. Tacked to the wall above her desk is a plaque recognizing her as Wyoming County's teacher of the year. Fastened to the classroom door is a cowboy boot worn by her late father, who drove a school bus through the region's winding roads for 20 years. From her classroom window, she can see a tiny steeple among the trees of a nearby knoll, the spire of a miniature church her grandfather built at the edge of their family property.

"I love this community," she says. "It's one big family—you feel like you belong, and you want to help the kids. I need to be here for them."

But at home, finances were tight. With an average salary of about $46,000, she and her colleagues are the fourth-lowest-paid teachers in the nation, behind Mississippi, South Dakota and Oklahoma. Many of her friends have moved to surrounding states for higher pay, or left teaching altogether. Adams's husband, a former coal miner who broke his back in a 2001 accident, received a regular disability check, but their combined income wasn't enough to support three children under 18.

Her second job as a private tutor became more regular; she used the money to buy her 15-year-old daughter a prom gown and her 5-year-old son a pair of athletic shoes. When the family needed new appliances, she went to Pineville Furniture because the store offers teachers credit and generous payment plans; the owner's daughter is an educator.

In the classroom, students were also struggling. The decline of West Virginia's mining industry has left parts of the state destitute, resulting in soaring unemployment and opioid addiction rates. Adams and her colleagues had always tapped their own pocketbooks to help their students; they saw it as just part of the job. But in recent years they found themselves spending significantly more on school supplies, field trips and gym shoes; Adams estimates that has added up to about $200 a year.

It was commonplace for social services workers to interrupt class to move children into foster care. "Just about every kid I've dealt with comes from a home where there aren't two parents around. And one kid this year said he only knew one member of his family who had ever had a job," says Will Daniels, who worked with at-risk students at nearby Westside High School. "It was my goal to be the best teacher out there, but slowly, through the climate in general and the bureaucracy, I had the wind taken out of my sail."

After working as a teacher for seven years, Daniels left at the end of this school year to run a lawn care business. He figures he can be more helpful creating jobs in the community than struggling in a classroom. He's part of a trend: West Virginia had more than 700 teacher vacancies this year, forcing administrators to combine grades and assign teachers to subjects for which they're not trained. At Adams's school, they couldn't seem to keep math teachers for more than a year before a better job lured them away. This year, the teacher wasn't even trained in middle school math, and she left too.

To cope with the educator shortage, lawmakers introduced a bill to lower teacher certification standards to fill job openings more easily. While Justice, the governor and coal magnate whom Forbes described as "West Virginia's only billionaire," had partly reneged on a promised pay raise, and the state had effectively raised health insurance premiums, this legislation seemed to bother Adams the most.

By early 2018, she and her fellow teachers were ready to push back. It wasn't simply the lack of money, she says. It was the lack of respect.

Decline of the Unions, Rise of Grassroots

At first blush, southern West Virginia seems an unlikely place for a radical teacher walkout. Pro-life billboards dot the wooded landscape, and three out of four voters here backed Donald Trump in 2016. State teachers do not have collective-bargaining rights, meaning their unions can't negotiate wages and benefits.

But the area's labor ties run deep. This is where school teacher turned organizer Mary Harris "Mother" Jones helped turn the United Mine Workers of America union into a political powerhouse in the 1910s; where 10,000 coal miners clashed with 3,000 lawmen at the Battle of Blair Mountain in 1921, the largest labor uprising in U.S. history; and where teachers, frustrated by meager salaries, launched an eight-day strike in 1990 that spread to nearly every county in the state and won them a $5,000 pay raise and other concessions.

"We all grew up going through the mine strikes," says Dale Lee, president of the West Virginia Education Association (WVEA), the state's largest teachers union. "You learned how much of a struggle these strikes could be, but you also saw good things come out of them."

Instead of curtailing labor activities, the teachers' lack of bargaining clout might have helped inspire radical measures. "In the absence of strong unions, we see teachers becoming more militant and less likely to compromise their original demands," says Erin McHenry-Sorber, an assistant professor of higher education at West Virginia University who studies rural schools and communities. "Without a strong union structure, it becomes a much more grassroots effort."

After "Fed-Up Friday," teachers in other parts of the state began staging their own one-day walkouts and labor actions. In mid-February, Lee and leaders from the state's other school employee unions called for a vote on a statewide walkout. On February 22, the superintendents closed every school in the state, and thousands of teachers flooded the Capitol. They wore "Red for Ed" shirts and tied bandannas around their necks, a reference to the red kerchiefs adopted by striking mine workers during the Battle of Blair Mountain. (Many believe these inspired the term redneck.) With skills honed by decorating endless poster boards, they made protest signs with slogans like "Education should not be a debt sentence." Some protesters got "55 strong" tattoos, a reference to all 55 counties taking part in the walkout.

"It was unbelievable how many people were there," Adams says. "Everyone was fired up." When lawmakers were in session, teachers chanted outside the chamber doors: "Fifty-five united!" During legislative breaks, educators swarmed legislators' offices. Each night, teachers planned new strategies using private Facebook groups. Adams, ever the organizer, fielded questions from her local union members and coordinated carpools to the Capitol, while her husband, John, took care of the kids. Several nights, she fell asleep still holding her cellphone.

The teachers singled out Republican Senate President Mitch Carmichael for spearheading political opposition to the teachers' demands. "I would walk out of the Senate chamber, and the place would erupt," Carmichael says. "There were chants against me. There were signs. I kind of became the villain." And when the lawmakers refused to meet their demands, the teachers refused to go back to school.

As the walkout stretched on, critics accused the teachers of neglecting their students and forcing parents to scramble for child care. "I think it's being disrespectful to our students, to our parents—all those associated with providing an education to our students," Carmichael says.

But there was little public outcry. Across the state, educators had helped communities prepare for school closures, organizing ad hoc day care centers manned by retired teachers. Then, four days into the walkout, a breakthrough. Justice, who had insisted there wasn't enough state money to address the teachers' demands, announced school personnel would receive a 5 percent pay raise. "We need our kids back in school," he declared. Lee and other union leaders were ecstatic. They told teachers to return to school.

Adams and her colleagues, however, were suspicious. The educators suspected lawmakers would scuttle the deal after they left the Capitol, so they refused to end the strike until the governor signed legislation. "I think the walkout was so successful because it was completely open and decentralized," says Ryan Frankenberry, state director of West Virginia's Working Families Party, a progressive political party that helped the teachers strategize. "No one owned the message, and no one controlled the movement. That allowed people to feel like they were part of the movement, not just following it."

Finally, on March 6, nine school days into the walkout, Justice inked a pay deal and pledged to set up a task force to address state insurance problems. Adams was by his side during the signing. Afterward, she walked through the Capitol. It was nearly silent. She sat on the front steps and cried. "I couldn't believe what we had done," she says.

'Don't Mess With a Teacher'

Richard Ojeda could see the strike coming. A Democratic state senator from coal country and a former paratrooper, he had launched a Junior ROTC program at a southern West Virginia high school, where he got to know the teaching staff. They often told him how disrespected by state officials they felt, how they constantly worried about going into debt. So, in January, as Adams geared up for the first strike vote, Ojeda took to the Senate floor. "We are sitting on a powder keg," he told his fellow lawmakers. "If you think teachers across this state are not saying the s-word, you are wrong."

The muscled and tattooed Army man with a buzz cut became the movement's rock star. Teachers chanted his name when he cheered them on at the Capitol, and they shared Ojeda memes online, like "Richard Ojeda was born in a log cabin…that he built with his own two hands." His image appeared on T-shirts and posters.

Before the strike, he was known for two things: getting jumped and beaten bloody by a brass knuckle–wielding assailant during a campaign event in 2016, and sponsoring a bill that legalized medical marijuana in the state. Now, he's running for Congress in West Virginia's 3rd Congressional District as the teachers' champion. His platform: instituting a "Medicare for all" health care system, raising taxes on natural gas drilling and building a booming pot industry. He hopes his support among educators will help him flip the most pro-Trump district in the state (the president scored more than 72 percent of the vote there). A poll in mid-June gave him a slight edge over his Republican opponent.

Ojeda credits the teachers with helping him secure the Democratic nomination (in a four-way race, he scored 52 percent of all Democrats' votes). He also thinks several Republican candidates in the state lost their primary bids because they criticized educators during the walkout. "You can only kick a dog so many times before it bites you in the ass," he declares, sitting in his campaign headquarters in Logan, a long-faded coal town in the southern part of the state. "The one person you don't want to mess with is a teacher. They are educated, they know how to do research, and they remember when you do them wrong."

In Adams's county, educators are gearing up for the fall elections. Teachers unions are hosting candidate forums, and one of Adams's colleagues is running for local office. "We are concentrating on November and working to get lawmakers who will support us into office," says Lisa Collins, who teaches at Baileysville Elementary and Middle School. "It's Republican versus Democrat: Who is going to be for us?"

Ojeda thinks his party will reap the benefits of the movement, insisting teachers could even flip the Legislature from red to blue. "Originally, we thought we would be lucky to win two seats," he says. "Now, we think we are going to take back the House and the Senate."

Carmichael, the Republican Senate leader, scoffs at the idea; Democrats are currently outnumbered by almost two to one. He does, however, concede that the teachers have amassed a newfound political influence. "I think they are effective," he says. "I think absolutely they can have an impact."

The political repercussions of the teachers' revolt could be felt well beyond West Virginia. Around the country, Democrats are hoping educators' wrath at tightfisted Republican lawmakers will lead them to vote en masse or even run against Republicans themselves. In Arizona and Oklahoma, dozens of teachers are now running for legislative seats. And in Kentucky, Travis Brenda, a high school math teacher with no political experience, defeated the state's House majority leader in the GOP primary—one of at least 34 current or former teachers who will be on Kentucky's ballot in November.

With organized labor's overall membership numbers and political power on the wane for years, teachers unions and other labor groups are also eager to take advantage of the groundswell among their ranks, especially one that illustrates shifting social dynamics in the workplace.

"Unions have to bear some responsibility for their diminishing power," says Ken Fones-Wolf, a labor historian at West Virginia University. "They are going to have to look to a very different model than what they had before. Unions were white and male and industrial. If they are going to regain some semblance of their influence in society, they have to be multiracial, and they have to embrace very different attitudes about gender. They have to reflect the way the workplace looks today."

Given the U.S. Supreme Court's recent decision on Janus v. AFSCME, a ruling that bars public-sector unions from mandating dues from employees who aren't union members, West Virginia is instructive, suggesting that labor can still have a major impact without strong, top-heavy unions. "We don't have collective bargaining. We don't have agency fees," says the WVEA's Lee. "But we've always known the value of grassroots organizing."

Still, Democrats and labor organizers shouldn't simply assume they can ride the teachers' passion and energy to victory. If they aim to take advantage of the groundswell, they're going to have to adjust their organizing tactics and policy positions to match the demands of the movement. As teachers in West Virginia and elsewhere have demonstrated, they're no longer willing to let others tell them what to do.

"I don't have any ill will towards our union, but I think something has to change," says Nema Brewer, a walkout organizer in Kentucky. "I think our education association saw itself as more of a lobbying group. We were saying the time for talk is over."

The Which-Side-Are-You-On Moment

On a warm spring day, 320 miles south of Charleston, more than 20,000 red-clad educators took over the streets of Raleigh, North Carolina, as part of a one-day walkout. As TV news helicopters hovered overhead and onlookers cheered them on, the crowd converged on the state Capitol, demanding that lawmakers inside increase teacher pay and school funding. The state had once boasted the sort of school salaries that lured teachers away from nearby states like West Virginia. But years of salary freezes and cuts to education spending led to North Carolina becoming the sixth state this year to witness a statewide teacher walkout.

There was no doubt what had inspired the protest. Mark Jewell, president of North Carolina's teachers union, had been a teacher and union organizer in southern West Virginia during the state's 1990 teacher strike, and he'd started planning the walkout in February as he watched his former colleagues shut down their schools. Now, teachers in the protest held up signs that read, "Don't make us go West Virginia on you."

Before the march commenced, Jewell had used a PA system to introduce a special guest to the crowd, West Virginia Education Association President Dale Lee. He received among the loudest cheers of the morning. The teachers here knew they were part of something bigger.

The National Education Association is drastically expanding the number of community-organizing trainings it is holding for teachers around the country; the organization is also launching a new program to instruct educators how to run for office. "It really is a which-side-are-you-on moment," says Randi Weingarten, president of the NEA's counterpart, the American Federation of Teachers. "You see on the ground, all over America, teachers taking action and having faith these actions will actually change things. At the same time, it's pretty clear the powers that be in this country are against unions and worker power. We are in a race."

In southern West Virginia, Tina Adams, one of the people who started that race, is thinking about her future. She worries about raising her kids in an area with so few opportunities; she feels the lure of better-paying teaching jobs in nearby states. But she knows leaving wouldn't be easy.

In May, she drilled math concepts into students fidgeting with restless energy from the approaching summer vacation. Her classroom shelves were overflowing with soda, snacks and other materials she's purchased for the upcoming spring fling dance. She wore a bright yellow dress in honor of her 40th birthday, and throughout the day she was treated to endless singing renditions of "Happy Birthday" from students and colleagues.

For now, she'll stay, organizing school field trips and quizzing her students on geometry. She's also ready for more drastic measures if the need arises. Her red bandanna is hanging on the rearview mirror in her car.

→ Additional reporting by Jason Pollack.

Correction: The previous version of this story said that North Carolina teachers protested in Charlottesville. It has been updated to reflect that the educators rallied in Raleigh.