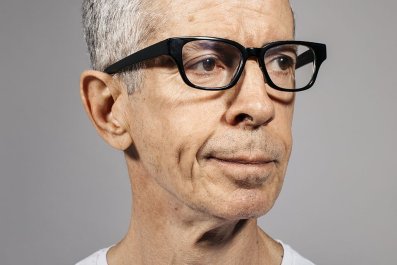

Filmmaker Bing Liu would prefer that you don't call his documentary "the Boyhood of skate videos," as one Indiewire headline described it. Not that he doesn't hold Boyhood director Richard Linklater in the highest regard (Liu's particularly fond of the director's 1990s Slacker); it's just that the comparison only "highlights the time aspect of Minding the Gap." Like Linklater, Liu filmed his subjects over a period of years (four, so not Boyhood's remarkable 12), but, he says carefully, "I was going for something a little more emotionally and thematically fresh."

It's Liu's polite way of saying that his movie—which premiered at Sundance and comes out in theaters and on Hulu August 17—contains none of the rose-colored nostalgia evoked in the work of Linklater, whose films often feature coming-of-age scenarios.

Liu's movie follows two struggling young skateboarders, 17-year-old Keire and 23-year-old Zack, from the director's hometown of Rockford, Illinois. Rockford was once the state's second-largest city, but like many in the Rust Belt, it has rapidly declined since the late 1980s. As the film details, 47 percent of its workers earn less than $15 an hour, and since 2010, its population has decreased more than any other Illinois city.

We first meet Keire and Zack skating through Rockford's ghost town streets. Keire, gentle and open, is reckoning with the death of his father and being the only African-American in their skate crew. He spends hours alone in his house, his mother shut in her bedroom. Zack, charismatic and irreverent, ran away at 16 and is now facing the birth of his first child with his 21-year-old girlfriend, Nina. The couple party, drink and smoke as they struggle with their dead-end present and not much hope for the future.

Early on, Keire confides to Liu that his late father used to beat him. "Did you cry?" Liu asks from offscreen.

"Yeah, sure," says Keire. "Wouldn't you?"

"I did cry," says Liu.

The 29-year-old director, it turns out, shares a lot with his subjects. He, too, was a skateboarder who grew up poor. Liu's intention was to remain behind the camera, but a year or so into filming, Nina confessed that Zack was hitting her. Later, Zack casually reveals to Liu that his father "kicked his ass" when he misbehaved. "I realized these were generational cycles of behavior," says Liu. "That really resonated with me."

Liu called his mother, Mengyue Bolen, who emigrated from China when he was 5, and asked if he could interview her about his own abuse at the hands of his stepfather. It's the only time that Liu—who served as director, cinematographer and co-editor on his film—hired extra crew. With one camera on his mom and another on himself, Liu presses her to process the trauma they had both experienced. "I tried to have this conversation with her when she divorced my stepfather four years ago," Liu tells me. "But it never lasted longer than 15 minutes before it got too upsetting. The camera allowed us to finally have a conversation."

Similarly, the camera became a kind of therapist for Zack. Liu captures shouting matches between the frequently drunk Zack and Nina, and she has a scar that she attributes to one of his blows. For much of the film, Zack denies abusing her, but toward the end he says to Liu, "You can't beat up women, but sometimes a bitch needs to get slapped."

"Zack likes to be the center of attention," says Liu. "Me and the camera were an outlet for that, but it shifted over time." Later, when he showed Zack the finished film, Liu saw he had tears in his eyes. Zack was relieved because he thought it would be a worse portrayal, says Liu. "We had a long conversation. It wasn't all about him; it was him reacting to Keire's and my stories. I asked him if he wanted anything changed, and he said no."

In addition to capturing lives with little economic hope, Minding the Gap is a moving portrait of young men growing up in Middle America at a time when they are getting a rough ride in popular culture. At the beginning of the film, Zack says, "Your whole life, society tells you, 'Be a man. You're tough. You're strong. Margaritas are gay.' You don't grow up thinking that's the way you are. You just act."

Zack didn't vote in the last election, but he was a Donald Trump supporter, and you see why that happened: He and Nina are the "forgotten men and women" Trump was appealing to in his 2016 campaign. "At first," says Liu, "we had Zack's political arc. He ran away from his father's house because he thought his dad was too conservative. Then, over time, things didn't go his way. His car broke down. He's waiting on his tax returns. He blames the government—all these things piled up, and you understood his reasoning for supporting Trump."

Ultimately, Liu adds, he didn't reference Zack's support of Trump in the film. "It took away from the evergreen quality," he says. "It would have colored the film's other themes too much."

Liu wasn't interested in adding to the deluge of patronizing Trump-country exposés, nor did he want to turn Rockford into "poverty porn." Since the election, he says, "the media has been focused on understanding 'the white working class.' Even if they are white and make a working-class wage, that's not how people from Rockford label themselves." Such classifying, he adds, comes with a "lack of empathy" and "a lens of judgment."

Zack got a lucky break after the Sundance debut. Another director offered him a lead role in a low-budget film. Nina, meanwhile, is working two jobs; she and Zack have split, and he pays child support for their 4-year-old son. She has spoken to survivors of domestic violence at screenings of the film.

Keire works at a Denver salad shop and plans to move to Phoenix with his girlfriend. Near the end of Minding the Gap, Liu tells Keire, "I'm making this because I was physically disciplined by my stepfather, and it didn't make sense to me. I saw myself in your own story." Keire is visibly taken aback. "Wow, Bing," he finally says. "I had no idea, dude. That's really cool."

Liu, now living in Chicago, has gone on to direct an upcoming episode for the Starz series America to Me (from Minding the Gap executive producer Steve James). He says he's doubtful he'll make a film as personal as Minding the Gap again. "People move into their 30s without processing their late teens and early 20s, when you start losing people—whether you just lose touch or lose them to drugs or suicide, which happens a lot in Rockford," he says. "This was a way to make sure I didn't fall into that trap."