Here's a game I play when I give a talk about the Supreme Court: "If you think Roe v. Wade was a persuasive ruling, raise your hand." In most venues, a majority of hands in the audience go up.

"Keep your hand up if you believe Bush v. Gore was also persuasive." Virtually all the hands go down.

I tell them, "You're hypocrites. The cases are about the same thing."

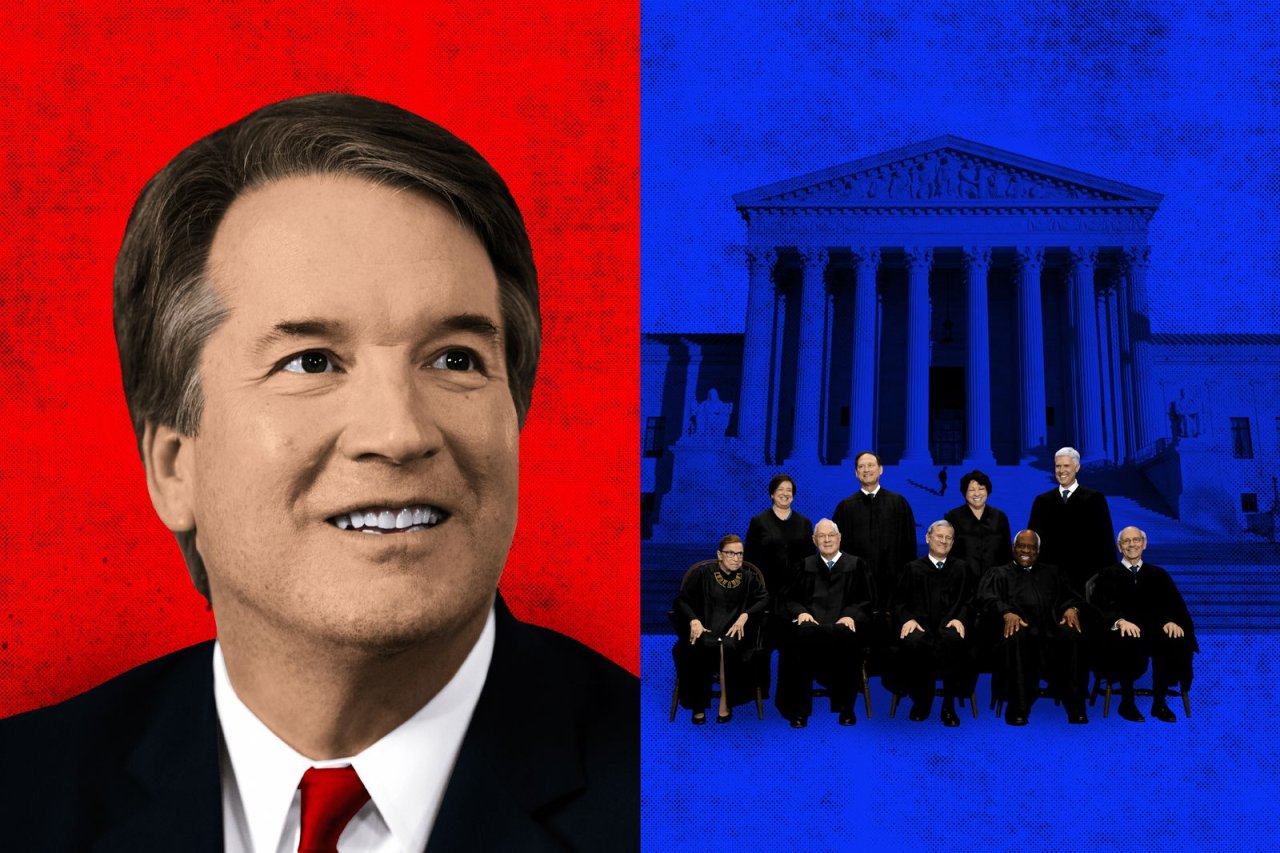

I'd like to see an amended version of this mischief at the confirmation hearings for Judge Brett Kavanaugh, President Donald Trump's nominee for the High Court. I want senators to ask Kavanaugh about Bush v. Gore, the 2000 ruling that stopped the electoral recount in Florida and awarded the presidency to George W. Bush. The question would be difficult to evade—and it might reveal what Kavanaugh thinks of the half-century march that has turned the court into the most dangerous branch of government.

Never before has the court been more central in American life. It is the justices who now decide the controversial issues of our time—from abortion and same-sex marriage to gun control, campaign finance and voting rights. A reckless president or witless Congress can do much harm, but in the long run it is the Supreme Court's unspoken power grab that most undermines self-government.

Liberals and conservatives ought to worry about this, no matter which party happens to be in charge today. But neither side even talks about the hubris of justices who so often substitute their own judgments for those of lawmakers in the elected branches.

More than Roe v. Wade, Bush v. Gore is a way to get Kavanaugh to confront the issue, a way to box him in strategically. Walk Kavanaugh through that ruling in hindsight and have him evaluate how the justices viewed their role. All the more because he's been a part-time professor of constitutional law at three law schools over the past decades, he surely knows how to take apart court opinions dispassionately. He must have strong views about what good ones look like and what bad ones look like, and it's not based merely on whether he agreed, hands up or hands down, with the end result of a ruling.

So, professor Kavanaugh, do you think the rationale of the Bush v. Gore majority about "equal protection of the laws" under the 14th Amendment was convincing or even plausible? Was it appropriate for the Supreme Court to intervene in a dispute that almost always was left up to the states, even over federal posts? Given that there was a specific constitutional amendment and a specific federal statute dealing with contested presidential elections—and both of those provisions dictated that Congress alone should be the arbiter—did the justices adequately justify their decision to step in? (The 12th Amendment and the Electoral Count Act of 1887 spelled out the details; in drafting the latter, Congress specifically decided the court should play no role.)

None of these questions calls for Kavanaugh to declare how he would have voted in Bush v. Gore. They don't require him to say which candidate he liked more. (Of course he was thrilled that Bush prevailed—Kavanaugh had worked on the litigation leading up to the court ruling.) Anything he mentioned couldn't remotely be viewed as a pledge on what he would do the hypothetical next time a presidential election was at a stalemate and the vote in the decisive state was essentially tied. No, the point would be to try to engage him in discussing how the justices went about their jobs.

Contrary to what conventional wisdom currently demands, my proposed line of questions is not about Roe v. Wade, which in 1973 created a constitutional right to abortion. That's the ruling too many senators fixate on too much of the time—understandably, given the political clout of both the pro-choice and pro-life movements.

The current court, with Justice Anthony Kennedy now retired, probably is split 4-4 about the constitutional correctness of Roe. Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan would vote to uphold it; Chief Justice John Roberts, along with Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito and Neil Gorsuch have all pilloried Roe, though we can't be certain that any justice other than Thomas would vote to actually overturn it. Given that the court is likely deadlocked, the open seat that Kavanaugh would fill is pivotal. So senators predictably want to know where he'll come down.

But no nominee will go near Roe v. Wade. That's because of Robert Bork, who was nominated to the court by President Ronald Reagan in 1987. During his confirmation hearing, Bork was honest and blunt in pummeling Roe's reasoning and was rejected in part because of that. Ever since, nominees have offered no tea leaves. They all respect stare decisis, the legal doctrine that prior rulings deserve great respect. They all accept Roe is certainly a precedent of many decades. And they won't disclose one iota of what they think of its reasoning or continued durability—or what they might do when (not if) the constitutionality of abortion winds up back in front of the court.

In 1991, Thomas took that MO to new depths at his hearings to become a justice. A Democratic senator, Patrick Leahy of Vermont, asked Thomas if during his second year at Yale Law School—when Roe was decided—he had ever thought about it. Thomas testified he had not. "My schedule was such that I went to classes and generally went to work and went home," he said.

Leahy was incredulous. "I'm sure you are not suggesting that there wasn't any discussion at any time of Roe v. Wade?" he asked.

"Senator, I cannot remember personally engaging in those discussions."

That alone might have been grounds to disqualify Thomas. (Yes, there was also the testimony of Anita Hill that Thomas had sexually harassed her while both were at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, but that's a different matter.) Even if his reply were not demonstrably false, did the country really want a justice so incurious that in law school he never engaged with anyone on the most challenging legal issue of the day?

Early on in his 33 years on the court, William Rehnquist suggested as much. "It would be not merely unusual, but extraordinary," he wrote in a 1972 case in which he refused to recuse himself, if nominees "had not at least given opinions as to constitutional issues in their previous legal careers. Proof that a justice's mind at the time he joined the court was a complete tabula rasa in the area of constitutional adjudication would be evidence of lack of qualification, not lack of bias." And yet Thomas got away with claiming he was a blank slate.

Two years after Thomas, Ruth Bader Ginsburg ably deflected just about anything of substance. If a question was about a specific legal issue, Ginsburg couldn't answer, lest she appear biased should the issue reach the court; if asked a hypothetical, Ginsburg couldn't possibly answer because it was so abstract. There you go: There weren't any answers she could give, so let's get lunch!

One scholar, in 1995, ridiculed Thomas's testimony and tweaked Ginsburg for staging a two-part "pincer movement" that cut off senators at both ends. "When the Senate ceases to engage nominees in meaningful discussion of legal issues, the confirmation process takes on an air of vacuity, and the Senate becomes incapable of either properly evaluating nominees or appropriately educating the public," the young scholar wrote in a law review. Confirmation hearings thus degenerated into a "vapid and hollow" "repetition of platitudes." The scholar was Elena Kagan.

Fifteen years later, after President Barack Obama nominated her to the court, Kagan showed herself to be just as good a field general as Ginsburg, walking back her views. "In some measure," she testified, "I got a bit of the balance off. I skewed it too much toward saying that answering is appropriate when it would, you know, provide some kind of hints." Well, we can't have that. "Vapid and hollow," indeed. Kagan, like Ginsburg, was easily confirmed.

Every nominee since Bork has followed a playbook written by a 26-year-old Justice Department lawyer in 1981 to prepare Sandra Day O'Connor for her confirmation hearings. "Avoid giving specific responses to any direct questions on legal issues likely to come before the court," the memo stated, recognizing that just about any legal issue could come before the court. The author of the memo? John Roberts, who scrupulously followed his own counsel when he was nominated for chief justice in 2005.

The excuse nominees successfully invoke is that intimating any thoughts about past cases would give the appearance of prejudging future appeals or even making a confirmation pledge in return for Senate support. But that argument is both too much and too little. Why is it self-evident that expressing a nonbinding view on a past ruling such as Roe makes one unfit to sit in judgment on a future analogous case?

More to the point, a nominee can have an initial judgment about the court's reasoning in a given case. The next case isn't going to be identical. There will be other lower court opinions in the interim, as well as new facts, briefs and academic commentary. If you're a good judge, you'll be open to the new. A forceful mind and an open mind aren't mutually exclusive.

And what about a justice who writes an opinion today stating, for example, that the Constitution doesn't confer a right to abortion? Is that justice forever rendered incapable of appearing impartial in subsequent abortion cases—or perhaps all cases on reproductive rights? Obviously not. But to the litigants in those future cases, whether Justice Bigmouth expressed a view in a previous ruling or during his confirmation hearings makes no difference. So why do we allow nominees to get away with saying virtually nothing?

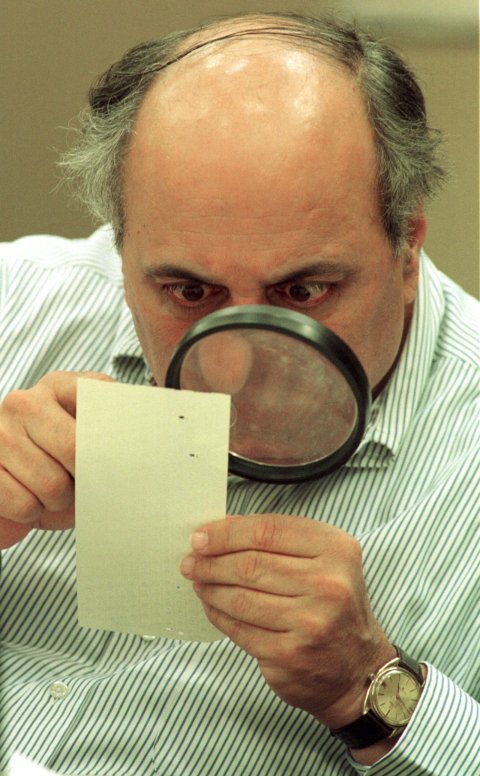

Bush v. Gore would provide senators a particularly easy way around the supposed problem. Abortion will clearly come before the court again. A situation like the recount in Florida in 2000? Highly unlikely. The justices in the 5-4 Bush v. Gore majority admitted as much. They voted to halt the Florida recount—thereby setting in stone Bush's 537-vote margin and awarding him the White House—based on the breathtakingly broad notion that "equal protection" was violated because Florida counties had different standards on which imperfectly marked paper ballots should be counted. But the justices said the ruling was "limited to the present circumstances"—a snowflake that melted before it reached the ground.

The justices did so in part because the decision was reached so hastily that they worried about its flaws: They didn't want the ruling's logic to throw into doubt countless other elections across the country that might someday be marred by variances in voting machines, ballot designs, instructions, hours, lines and personnel. The justices also understood that the election scenario before them was not going to be replicated. (A deadlocked presidential election had also happened in 1876, but once-a-century isn't exactly a major risk.)

Kavanaugh would sound downright silly if he claimed he couldn't talk about Bush v. Gore because its ghost might reappear. Similarly, he would be hard-pressed to suggest the general issue of equal protection presented in Bush v. Gore would come up again, given that the court had made very clear it wanted to stay light years away from the issue. Kavanaugh simply wouldn't have much room to dodge questions about the ruling, especially if a competent cross-examiner was asking them.

Bush v. Gore is the Supreme Court's worst example of recklessness since the Dred Scott decision in 1857 that said Congress lacked power to ban slavery in the territories. Several justices realized how bad their ruling was. Justice Antonin Scalia reportedly told a colleague that the equal protection reasoning about Florida procedures was "a piece of shit."

Scalia, being Scalia, never indicated he regretted it, instead advising critics, "Get over it!" His justification for court intervention, he told an interviewer, was that "we were the laughingstock of the world—the world's greatest democracy couldn't conduct an election." Somehow Scalia—the great constitutional textualist—omitted to cite where in the Constitution he had unearthed a "laughingstock of the world" clause that allowed the court to ignore explicit text that left to Congress the resolution of electoral disputes for the presidency.

O'Connor was even more cynical. As I report in my new book on the court, her husband, John, said a few months after the ruling that she had voted as she did—even though "she knew it was wrong"—in the hope that she would be able to retire sooner and ensure a Republican president would get to name her successor.

O'Connor and Scalia were in the majority. The four dissenting justices in Bush v. Gore excoriated the details of the ruling even more—but also the court's choice to get involved at all. The court has nearly complete control over its docket. It could easily have declined to hear the appeal, as most legal experts on both sides of the aisle expected at the time. John Paul Stevens saw Breyer at a Christmas party on the Friday night that the Bush campaign filed its appeal seeking to halt the Florida recount. "I guess we'll have to meet tomorrow—it'll take us about 10 minutes," Stevens said. He was right that it didn't take long, but he got it exactly opposite. The justices issued an emergency order to block further counting.

Three days later, when the court issued its final ruling for Bush on December 12, 2000, Stevens and Breyer each lamented the legacy the ruling would leave. "Although we may never know with complete certainty the identity of the winner of this year's presidential election," Stevens wrote, "the identity of the loser is perfectly clear. It is the nation's confidence in the judge as an impartial guardian of the rule of law."

Breyer described Bush v. Gore as the "quintessential" political dispute calling for judicial restraint. It was, he wrote, marked by an "intractability to principled resolution," "sheer momentousness…which tends to unbalance judicial judgment," and "the inner vulnerability, the self-doubt of an institution which is electorally irresponsible and has no earth to draw strength from." Breyer concluded: "What it does today, the court should have left undone."

Kennedy, the most unapologetic interventionist the court has had in three decades—and who wrote most of its unsigned opinion in Bush v. Gore—dismissed the concern. Straight-faced, he ended his opinion with a peroration about how "none" stood "more in admiration" than the justices of "the Constitution's design to leave the selection of the president" to "the people."

The claim was laughable, for it was the political process that Kennedy, especially, didn't respect. Whether it was campaign finance or voting rights or gun control or gay marriage, Kennedy rarely trusted elected representatives to sort it out. In the presidential election, Congress—elected by "the people"—couldn't be entrusted to settle things. Why was it up to the court? Kennedy blamed the litigants. "When contending parties invoke the process of the courts," he wrote, "it becomes our unsought responsibility to resolve the federal and constitutional issues." That was overwrought hooey. The justices were forced to hear nothing.

In Bush v. Gore, where would Kavanaugh place himself on the spectrum between Kennedy and Scalia, on the one hand, and Stevens and Breyer, on the other? Kavanaugh already played dual roles in the case—working for Bush's legal team in the appeal and then as a TV talking head in front of the court after the justices heard arguments. In the latter role, tellingly, he didn't offer any disagreement with the court's choice to get involved. The justices, he told CNN, were only trying to determine the "enduring values that are going to stand a generation from now."

Fair enough. But it's time to go further. How does Kavanaugh think the court ultimately did on that "enduring values" thing? Does Bush v. Gore, in retrospect, stand up? He need not take any position on what he might do on, oh, let's say a Trump-Biden tie in 2020. Just give us something that reflects your considered judgment, all the more since in the interim you've become a federal judge. Kavanaugh has proven he can be retrospective, analytical and ostensibly dispassionate. Although he was a key member of the Kenneth Starr investigation into President Bill Clinton in the 1990s, years later Kavanaugh wrote in a law review that investigations into presidential misconduct might best be postponed until a presidency ended.

If Kavanaugh answers honestly and thoughtfully on Bush v. Gore, we'll get valuable insight into how his mind works, where he sees the Supreme Court fitting into the larger federal system, and whether he'll be yet another justice who embraces the court's triumphalism. If he clams up, we'll justly conclude he's merely another disingenuous nominee who will say almost anything—or, rather, nothing at all.

David A. Kaplan is the former legal affairs editor of Newsweek. This is an excerpt from his recently published book, The Most Dangerous Branch: Inside the Supreme Court's Assault on the Constitution (Crown). Twitter: @dkaplan007