Mike Sniper was working at a record store in Brooklyn, New York, when he got the call. A man had died and left behind a mountainous record collection. It was the mid-2000s; Sniper was a buyer and pricer for used vinyl. Could he appraise the collection?

The task was more harrowing than he had imagined. "It turned out the guy died in the apartment, and no one found him for, like, two weeks," Sniper says. "It reeked of death." The man had been a sci-fi critic and, based on his East Village apartment, a hoarder. "There were records in the stove and in the refrigerator. Tons and tons of porn DVDs everywhere."

But there were treasures scattered amid the mess: "It was the kind of collection you don't see very often," Sniper says. "Original Sun Ra records, really rare punk records, original Velvet Underground LPs... [He was] clearly an interesting guy who at some point lost his shit and became a hoarder."

One LP from 1982 caught Sniper's eye. The cover was macabre, with the title, Roadkill, plastered in bleeding red type. The band was called Capital Punishment. There was scant information online. "I'd never heard of it, so I put it on: Ah, this is actually kind of cool," Sniper remembers. "I wound up buying it for myself."

Later, Sniper glanced at the liner notes and spotted something interesting: "It said: 'B Stiller.' I went, Huh! It can't be." But his hunch was correct. Capital Punishment was Ben Stiller's weirdo high school band, and Roadkill the crown jewel of the comedian's secret punk past.

Now, more than a decade after that discovery, Sniper is reissuing the long-lost album on his own indie label, Captured Tracks, finally bringing Roadkill's warped textures to a mass audience. He even managed to inspire an reunion of the bandmate: Kriss Roebling, guitarist and vocalist, is still a musician, as well as a documentary filmmaker; Peter Zusi, guitarist, is now a professor of Slavic studies in London; bassist Peter Swann is a judge on the Arizona Court of Appeals; and Stiller, the drummer, is, well, Ben Stiller.

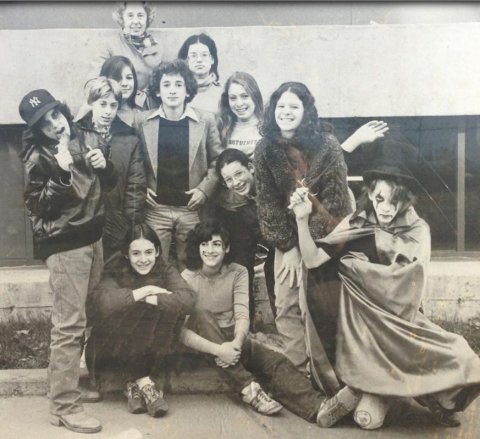

The band's story begins at The Calhoun School, a Manhattan private school, during the late 1970s. Roebling (a descendant of the Brooklyn Bridge designer, John A. Roebling) was the ringleader. "Kriss was a complete nut, in the best sense," say Zusi. "He's got a slightly crazy streak." Once, for instance, he convinced his friends to explore the secret steam tunnels beneath the Waldorf Astoria.

But Roebling's real passion was music. In 1977, he formed an early incarnation of Capital Punishment as a Kiss-inspired band. Later, he recruited two childhood friends, Zusi and 14-year-old Stiller, to join. By this time, says Roebling, his musical interests had expanded: "We were getting turned on to very different kinds of music—Brian Eno-based stuff, CAN, David Bowie."

"I was not in any way as sophisticated as Kriss," says Stiller, whose parents, like Roebling's, were actors (Jerry Stiller, of Seinfeld fame, and Anne Mear.) "He was more into the alternative and a little bit of punk. I was into The Cars and Duran Duran. And I loved The Beatles. The night John Lennon died, I was one of those people outside the Dakota [Lennon's New York City apartment building] all night."

During a 2014 Tonight Show appearance, Stiller described Capital Punishment as "sort of post-punk, neo-goth, urban-experimental." He was, he joked, "the Ringo of the band." But what he lacked in musical prowess, he made up for in charisma—even at 14. "Ben was funny, definitely a performer, but not in an overly gregarious way," says Zusi. "If you asked people in our school, 'Who's most likely to become a famous movie star?' they probably would have said Ben."

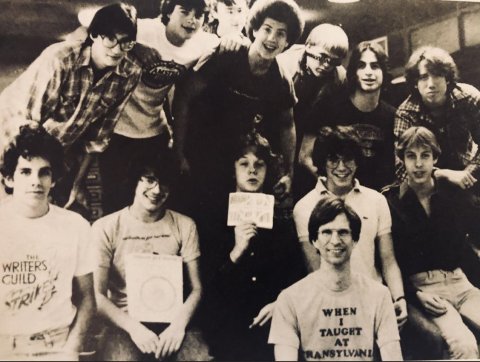

Around 1981, when the bandmates were in high school, they decided to record an album. Roebling had a guitar teacher who'd shown him some recording techniques and introduced him to a friend with a studio. His parents agreed to cover the cost. "My parents were both artists themselves," he says. "They loved stuff that wasn't necessarily the norm." Skill was not a barrier. "We were rank amateurs," says Roebling. "That was both the problem and the charm."

"For me, [recording the album] was just being really nervous that I'd be able to play something that would be usable," recalls Stiller. "The music definitely was a little strange. I remember thinking, 'Wow, this is really weird.' [But] it was much more fun than homework, to actually go to a real recording studio."

The band ended up spending nearly a year recording Roadkill in fits and starts, juggling studio time with English and biology. Swann, the future judge, joined the band during the recording. ("There was a better bass player in our school who was sick that day," he confesses.)

The resulting album is far more outré than you'd expect from a bunch of baby-faced teens. There are sound collages, bagpipes, burbling synthesizers, horror-movie effects—and that's just in the first three tracks. The opening number, "Necronomicon," juxtaposes news snippets about the Hillside Strangler with a wandering sitar solo ("I brought that friggin' thing back from New Delhi without a case," Roebling says). From there: cartoonishly warped synth-pop ("Roadkill"), Bowie-meets-The-Residents acid-glam ("Confusion"), a hysterical sendup of waiting-room muzak ("Muzak Anonymous") and so on. On "Delta Time," Roebling affects a British accent.

While Roebling was the chief creative engineer, there is one fleeting glimpse of Stiller's comedic future. At the end of "Delta Time," the future Zoolander star can be heard goofing around in character as Merv Griffin from SCTV. "We were big SCTV freaks," Roebling says. At the time, Stiller was more interested in being a filmmaker than a comedian. "Growing up with my parents, who were in comedy, the rebellion was to go against it," he says.

The teens' experiments occasionally bewildered the studio employees. "There was a professional engineer who'd look at us like, You guys must be insane…. 'OK, let's try it,'" says Zusi.

In pre-gentrification Manhattan, nspiration was everywhere. "There were new genres being born every couple of weeks," says Swann. "Back then, the Upper West Side was like an artists' colony. You couldn't walk a block without encountering some new form of expression."

"That New York had a lot more edge to it," Stiller adds. "We would go down to [the club] Danceteria. I was sneaking into Studio 54 with my sister when I was 13."

When Sniper heard the album 25 years later, he was impressed by its defiant wackiness, reminiscent of avant-garde groups like Cabaret Voltaire, The Residents and Throbbing Gristle. "In my head, [Capital Punishment] was part of the downtown art scene of the early '80s," he says. "I thought these were people playing at Max's Kansas City. I had no idea they were high school kids."

In reality, the band hardly gigged at all, aside from one or two high school talent shows. "If you hear the album," says Zusi, "you realize it's not music you can play live."

Nor was it music likely to land these teens a record deal. Roebling paid to press somewhere between 500 and 1,000 copies of Roadkill and self-released it. He remembers selling the album on consignment to indie and punk record stores like Rocks in Your Head, the once-legendary SoHo outpost. "I don't think we took any money for it," Zusi says. "We were just thrilled at the idea that somebody might buy them."

Then life went on. The four teens graduated and drifted out of touch, and Roadkill faded into the distant past. Stiller would occasionally pull out the album to show his kids. "I'd put it on the turntable and say, 'We actually did this, 30 years ago!' They would laugh and get a kick out of it."

But unbeknownst to the band members, the album became a collector's item for a certain breed of bespectacled record store nerd in the 2000s. About five years ago, Roebling looked it up "just for shits and giggles. I went on Discogs.com, to see if it even existed on anyone's radar," he says, "and was shocked to find someone trying to get $500 for it. Which, to me, was mind-boggling."

Stiller's subsequent fame contributes to the album's novelty appeal. But until fairly recently, the actor's involvement with Capital Punishment had never been publicly confirmed; the liner notes only use his first initial. (Stiller is pictured in a grainy cover image, but unrecognizable behind novelty shades.) "Nobody knew who we were," Swann insists. He claims to have heard fuzzy stories about the record being played and gaining traction behind the Iron Curtain in the 1980s, but "I still have no independent evidence to back that up."

Meanwhile, Sniper was about to realize his longtime dream of reissuing his mysterious artifact. In 2008, he founded his label, Captured Tracks, and five years later one of his employees finally tracked down Roebling. "I thought, Uh-oh, this is going to be some crazy person collecting stuff in their mom's basement," he says. But Sniper's label was legit and his interest in the music sincere. He didn't just want to rerelease the album. Sniper wanted a deluxe reissue; included are an early Capital Punishment song, from 1979, and a final recording from 1983.

Stiller was totally on board, and happy to reconnect with some of his oldest friends. "He was doing all this press before we could sell anything—on Jimmy Fallon, Howard Stern," Sniper says.

In March, the four bandmates gathered together for the first time in decades. "It was like we had paused the VCR and hit Play again," says Swann. They recorded several Capital Punishment reunion tracks in Brooklyn. Stiller, for one, had noticeably improved. "I picked up the drums again six or seven years ago," he says. "Just give me 35 years to practice, and I'll be fine."

Sniper, who had feared they would be terrible, was sincerely impressed by the results. "It's almost like this is their version of a high school reunion, making more weird music," he says. Roebling says the songs will be released "hopefully in the not-too-distant future."

The belated spotlight amuses Roebling. "I told my wife that this is my Searching for Sugar Man moment." So far, says Stiller, there is no talk of a tour. "I wouldn't want to inflict that on anybody," he says. "At some point, we might play in front of people."