On Donald Trump's first visit to Beijing as president in late 2017, as trade tensions with China were building, the Chinese laid the hospitality on thick. There were tours of the Forbidden City, visits to museums housing priceless antiquities and elaborate banquets with President Xi Jinping and the rest of the Chinese leadership. When it came to substance, Beijing signed letters of intent for deals with U.S. companies ostensibly worth $250 billion, and Xi pressed Trump on the value of a series of high-level, biannual talks between Washington and Beijing known as the "strategic and economic dialogue."

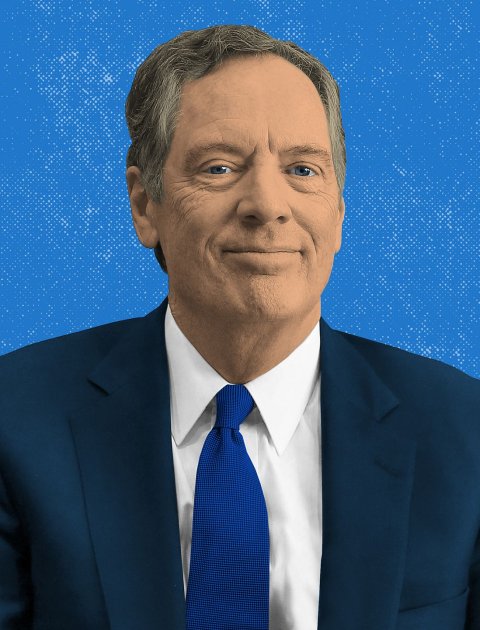

Robert Lighthizer, along for the visit as Trump's U.S. trade representative (USTR), was not happy. Begun during the George W. Bush administration and continued under President Barack Obama, the SED, as it became known in Washington, was exactly the sort of open-ended gabfest that Beijing loved and Lighthizer loathed. He believed these sorts of confabs were designed to string the U.S. along and avoid dealing with the trade problems at hand. "Strategic and economic bullshit," he once called it. After the second day of talks, Lighthizer met with Trump privately. "You're being played," he told the president, according to multiple White House sources. The assessment jibed with Trump's gut instinct as well; he reassured Lighthizer that he would keep trade as the focal point of discussions with Beijing moving forward. Ever since that visit, Lighthizer has become the most influential voice in Trump's ear when it comes to what is arguably the administration's most pressing issue: trade relations with the world's second-largest economy.

To the dismay of Wall Street and much of establishment Washington—neither of which wants to see trade with China seriously disrupted—Trump's inclination is to be tough on Beijing. Policy wonks in both parties love to deride Trump's "instincts" as the impulses of an accidental, know-nothing president. Lighthizer's presence at his side makes that a far more difficult argument.

As far back as 2010—well before trade tensions with China consumed Washington—Lighthizer wrote a lengthy, scathingly detailed and (so it happened) largely prescient piece for the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, a group mandated by Congress to present an annual report on the security aspects of Washington's economic relations with the People's Republic. He lampooned the wildly rosy assessments of what China's accession to the World Trade Organization would mean for the U.S. economy—and for manufacturing workers in particular. He pointed out the various policies in Beijing that distort trade, penalize foreign companies and tilt the playing field in China toward homegrown companies. He warned of industrial policies that were designed to promote the development of Chinese technology, again at the expense of foreign competitors.

Today, this is standard fare for the policy mills in Washington; seminars and conferences abound at places like the Center for Strategic and International Studies or the Brookings Institution mulling what to do about trade with China. Remarkably, there is now widespread consensus at least around the Trump administration's—which is to say, Lighthizer's—diagnosis of the problem. "[It] has quite fairly identified a series of problems in the [trading relationship] with China," acknowledges William Reinsch, a former Clinton administration official who's now a senior adviser at CSIS. How to best respond is another matter.

When Trump appointed Lighthizer, the free trade purists—principally the Fortune 500 and their lobbyists, as well as powerful agriculture interests—knew they had a challenge. In their view, he's a protectionist hack: Lighthizer worked for years as a trade lawyer at Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom, the prominent Wall Street law firm where he represented American steel producers in a variety of cases involving unfair trade practices by foreign countries, such as dumping goods below cost in the U.S. market. Critics saw him taking the book of the old clients who made him wealthy. And since Trump is a protectionist, they argue, Lighthizer is abetting his boss's worst instincts—and risking an ever more damaging trade conflict between the world's two financial powers.

The caricature mildly amuses Lighthizer, because he came to his "trade hawk" status through one of the most politically conventional paths imaginable: His first tour in government was as a staffer on the Senate Finance Committee under Bob Dole, the mild-mannered Republican from Kansas who ran against and lost to Bill Clinton in 1996. He then went to work as a deputy at the agency he now runs, the USTR, during the Reagan administration. He was recruited by—and reported to—another milquetoast moderate, former Tennessee Senator Bill Brock, and served an administration headed by one of the most pro–free trade candidates of the 20th century.

Lighthizer considers himself a "rock-ribbed Republican" who believes in free trade, he says. "Always have," he's said. Like Reagan, however, he is not dogmatic about it. Born and raised in Ashtabula, Ohio, he saw a vibrant steel industry, the cornerstone of the region's economy, get decimated by offshoring in the 1970s and '80s. Lighthizer's willingness to deviate from Republican trade orthodoxy, he says, stems from getting "hit in the head by reality."

During his first tour at the USTR, the major trade problems came from Japan. Both formal and informal trade barriers made Japan all but impenetrable to imports. At the same time, it built competitive companies in key industries, flooding American markets with automobiles, steel and semiconductors. U.S. companies were getting crushed by Japanese competition back then. Dogmatic free traders seemed to think the best course was to "sit back and take it," as Clyde Prestowitz, a former Reagan-era Commerce Department official, puts it.

But Reagan was willing to use a powerful tool Congress had given the executive branch in 1974: the ability to bring unilateral trade action against foreign competitors thought to be unfairly injuring domestic competitors, bypassing what was then known as the General Agreement on Tariff and Trade, the forerunner to the WTO. Lighthizer was central to putting together these so-called "super 301" cases (named after the section of the 1974 trade law) against Japan. They threatened tariffs on Japanese-produced goods in order to provide relief to a range of U.S. industries, including semiconductors and satellites.

The moves infuriated Tokyo—its trade minister at the time decried Washington's "Mafia tactics"—but they got Japan's attention. In semiconductors, for example, the U.S. and Japan agreed to a series of measures that would increase over time Japan's purchase of American-made computer chips, while also implementing a complex pricing mechanism that was intended to prevent Japanese "dumping" of chips in the U.S. market (that is, selling them below cost). The U.S. separately pressured Japan's car industry to assemble automobiles in the U.S. rather than export them, which would create jobs in the U.S. and

reduce the bilateral trade deficit with Tokyo. Today, there are 24 Japanese car plants in the U.S.

As far as Lighthizer was concerned, the exceptions to the Reagan administration's pro-trade policies were effective. His critics have said because Japan, a key U.S. ally, did a series of trade deals with Washington to help defuse a bigger crisis, Lighthizer is naïvely assuming China—emphatically not a U.S. ally—will do the same.

He declines to compare the two situations, but USTR staffers and people who have worked with Lighthizer stress that he's anything but naïve. He understands that the case of China is more complicated than Japan was in the 1980s. He has said the key to a successful trade deal is to know "where the leverage is," and in this case he believes it's keeping the pressure on China at a time when it is arguably more economically vulnerable than the U.S., given its rapidly slowing economy.

"That doesn't mean he's slaphappy about tariffs and the risks they pose to U.S. business and the stock market," says a source who sees Lighthizer almost daily. Nor is he necessarily "all about the bilateral trade deficit." The key longer-term issue, as the USTR has laid out in its 301 complaint about China, is persuading Beijing that there will be significant consequences if it tries to build national champions in key high-tech industries at the exclusion of foreign competition, via state subsidies, intellectual property theft and forced technology transfer from the U.S. and other developed countries. If doing so inflicts some economic pain in China (thanks to tariffs) and limits Chinese direct investment in the U.S. while also causing U.S. stock investors to head for the exits in fear of a trade war, Lighthizer appears to be fine with that.

Trade experts, such as Reinsch, say that tack risks disaster. "The question is, Can you come up with a cure that's not worse than the disease?" he says. "Are you going to crater the two biggest economies in the world in order to get China to alter its behavior on cybertheft and forced technology transfer and the protection of its domestic companies? Are we really going to get China to upend the way it does business [and] is there a way to do that without causing a crisis?"

In the corridors of the Trump administration, those, in fact, have been key questions asked by Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin and national economic adviser Larry Kudlow, who constantly remind the president that his beloved stock market does not like trade conflict. They favor a lighter touch than Lighthizer, who wants to keep the pressure on Beijing.

For the moment, Lighthizer's view is closer to Trump's, though all involved are acutely aware of how easily the president can change his mind. The temporary suspension of tariffs on Beijing, which Trump agreed to after dining with Xi last month at the G20 in Buenos Aires, Argentina, expires March 1. If Trump balks at a deal with China that doesn't give the U.S. all that it seeks, and he reimposes tariffs, it is likely that Lighthizer's view will have carried the day. Whether that will be a good thing or not is an entirely different question. —BP