Today, we started a big, beautiful wall." It was mid-February, and President Donald Trump was crowing at his first MAGA rally of 2019. There was no new wall, of course, and everyone in the border town of El Paso, Texas, could see that. But in the sea of red hats at the County Coliseum, the line was met with roars of approval. What mattered was that the president was owning the libs, undeterred several weeks after provoking, then caving over, the longest government shutdown in U.S. history.

Before Trump rolled into town, El Paso's sheriff was telling anyone who would listen that El Paso "was a safe city long before any wall was built." Republican Mayor Dee Margo similarly denounced Trump's claims during his State of the Union address that El Paso was riddled with crime until it put a barrier in place. Media outlets like the Associated Press published stats: El Paso's murder rate was already less than half the national average in 2005, a year before the city's border fence with Mexico went up, and for almost a decade before, El Paso was rated one of the three safest major cities.

But the crowd was there to hear Trump's version. "Murders! Murders! Murders! Killings! Murders!" the president shouted, before turning on El Paso's leaders. "They're full of crap when they say it hasn't made a big difference," the president told the crowd. "Thanks to a powerful border wall in El Paso, Texas, it's one of America's safest cities now."

The wall has always been pure Trump shtick. And, as the president heads into the second half of his term, the American public seems to be tiring of it. Border states are split over the topic. The government shutdown slammed Trump's approval ratings and squeezed his beleaguered party in Congress almost to the breaking point. Still, Trump gave up only as one major international airport was closing terminals and Federal Aviation Administration unions and airlines warned of imminent safety concerns. And when he pushed ahead with a national emergency declaration to fund his concrete or steel-slatted barrier, less than 40 percent of Americans supported him, according to multiple polls.

But as with all things Trump, there is some method to the madness: The wall is not so much about policy and security as it is about politics and symbolism. Started by his campaign advisers as a rhetorical device to keep the notoriously off-script Trump on task, the wall elicited cheers, then rapture among conservative crowds: "Build! The! Wall!" There would, of course, be other plans: Ban Muslims, deport "bad hombres" and restore "law and order." But nothing beat the wall, which served as not only a singular campaign promise in Trump's self-described "war on illegal immigration," but also the physical embodiment of the identity politics that defined his bid from the outset.

By declaring Mexican immigrants "rapists" on the first day of his campaign, he promoted an us-vs.-them worldview and found a political vein other politicians had not dared tap—or, if they had, only gingerly: whiteness. Trump won over millions of Americans whose attitudes could be summed up in the words of one supporter after his election: "He said things that people were thinking, not saying," Rhode Island's Eileen Grossman told USA Today.

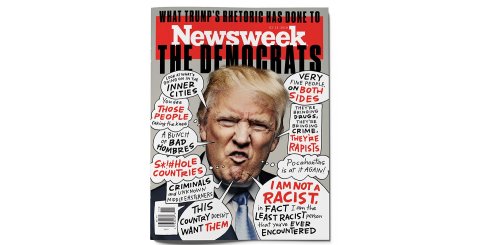

What they were "not saying," of course, had mostly to do with race. And Trump has said quite a bit over the past two years, from defending the "very fine people" at a white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, to disparaging the "shithole countries" to shutting down the government and declaring a national emergency over an "invasion" of migrants that could "infest our country."

The 45th president has changed the way America talks about race—with profound consequences for the public (hate crimes spiked his first year in office) and both political parties. Republicans and Democrats are grappling with whiteness as an organizing element in American politics. Trump has been clear about his intentions. "I didn't need to do this," he said as he declared a national emergency over the wall. "The only reason we're up here talking about this is because of the election."

Trump's strategy to rally white Americans poses significant challenges for both parties. For Republicans, it further alienates an increasingly diverse electorate. The number of white evangelicals and white voters without college degrees—the backbone of the GOP—is shrinking, while the number of African-Americans and Latinos is growing. Trump's 2016 victory was narrow—he lost the popular vote. And the party's midterms losses suggest that his all-out racial messaging strategy is alienating college-educated white suburbanites. According to Republican strategist John Feehery, Trump now needs to convince them that "he is not the racist the media and Democrats say he is."

Trump is unique in the scale and depth of his appeal to WHITENESS, his sustained racially charged campaign to "Make America great again" UNMATCHED in modern political history.

But Democrats face an even thornier problem than Republicans. The party has defined itself in opposition to Trump and his small-tent agenda, but in doing so, it is promoting a vision equally rooted in race and identity. Leaders have organized around key parts of their base—women, African-Americans, LGBTQ people—and the issues that have kept these groups from fully participating in American society, including abortion restrictions, racism in the criminal justice system and a ban on transgender troops in the military. Of the identities, race is the broadest and most visceral, the legacy of slavery passed down through the decades in white guilt and black pain. When a photo surfaced from the 1980s medical school yearbook of Virginia's Democratic governor, Ralph Northam, showing one person in blackface and another dressed as a member of the Ku Klux Klan, party leaders called on him to resign (he refused but vowed to dedicate the remainder of his term to racial equity). A number of declared presidential hopefuls, including Senators Kamala Harris and Elizabeth Warren, have recently endorsed some form of reparations for African-Americans, a controversial proposal that Democratic presidential hopefuls opposed just three years ago in the 2016 campaign.

"Americans must thoughtfully pursue an expanded, identity-conscious politics," Georgia's rising political star Stacey Abrams wrote recently in Foreign Affairs. "By embracing identity and its prickly, uncomfortable contours, Americans will become more likely to grow as one."

But there is one claimed identity that Democrats do not embrace: the white one. And victory in 2020 might run directly through the states where it could play a decisive role.

In 1964, after President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act, it's said he turned to a key aide with an air of political resignation and lamented, "We have lost the South for a generation." Johnson was right, though his analysis was too narrow. In fact, that year, he became the last Democrat to win the white vote nationally. Ever since, with the landmark legislation realigning the major political parties, race has increasingly become a tool, and indicator, of political persuasion.

To exploit racial resentments and capture white voters, Republicans dog-whistled away—sometimes shrilly, sometimes gently. Richard Nixon declared a "war on crime." Ronald Reagan went after "welfare queens." George H.W. Bush conjured the specter of African-American prisoner Willie Horton, who raped a white woman while on furlough. Democrats, in turn, pursued a series of measures, including tough sentencing laws, to prove themselves tough on crime and compete for the white vote. Hillary Clinton, in remarks many criticized for their racial overtones, famously spoke of young "superpredators" and the need "to bring them to heel."

But Trump is unique in the scale and depth of his appeal to whiteness, his sustained racially charged campaign to "make America great again" unmatched in modern political history.

And before the 2016 election, few appreciated the magnitude of the audience for such a message. According to Ashley Jardina, a Duke political scientist who studies whites and American politics, at least 40 percent of Caucasians acknowledge having some degree of "white identity," a loose term that exists on a spectrum. Racists who support hate groups like the Ku Klux Klan are a small minority of these so-called white identifiers, about 10 percent. The rest, she says, are usually more animated by political and economic forces. The common thread among white identifiers, she said, besides whiteness, is a sense of aggrievement.

"When we think of racial prejudice, we think of antipathy toward people of color, a general sense of animus," Jardina says. "There is a subset of people in the U.S. who feel their white race is important to them and feel the demographics are changing and the privileges and advantages that they have are under attack. That is different from 'I just don't like black people.'" She acknowledges that there is a relationship, "but it's not the same thing, although the consequences of these two attitudes might sometimes be the same."

Eddie Glaude, a Princeton University religion professor who writes about race and politics, is less generous; he considers any level of white identity as racism by another name. "White identity is this investment in the belief that because of the color of one's skin, one should be accorded more benefits than others," he says. "Society organizes around the belief that whites matter more than others, and white identity is thrown into crisis when it seems as though that is no longer true."

White identity, he argues, is bogus because it doesn't stem from the kind of historical discrimination suffered by women, gays and people of color. In other words, whites have always and still do dominate the nation, economically and politically, so to proclaim one's white identity is to celebrate a supremacist status.

Between the CIVIL RIGHTS movement and Obama, "we didn't talk about white people because their dominance and privilege was SECURE."

Although the issue failed to draw significant attention until Trump was elected, the population of white identifiers has remained relatively stable for the past nine years, based on American National Election Studies data and other sources analyzed by Jardina. (She says there is insufficient national data on the issue before that time). Two major events, however, combined to stoke their sense of lost power: the election of the first black president in 2008, followed by the heavily publicized results of the 2010 census, which found America at a demographic tipping point. About half of all U.S. births were minorities, analysts said, putting the country on track to become "majority-minority" by the 2040s.

While some experts disagreed with that prediction—arguing that the census counted some mixed-race people as nonwhite who may see themselves as white—the narrative was fodder for conservative media, in particular Fox News, which repeatedly seared it into the public imagination. "Census Shows White Babies Now the Minority," a website headline read. Google searches for "white privilege" and "white genocide" began rising in 2012 and are now at "unprecedented heights," according to Eric Kauffmann, professor of politics at Birkbeck College, University of London, who recently published White Shift: Populism, Immigration and the Future of White Majorities.

In addition to the perceived threat of a growing minority population, whites without a college education faced a very real problem: death. Those with no more than a high school diploma were dying off at rates 30 percent higher than African-Americans, many to "deaths of despair," as Princeton professors Anne Case and Angus Deaton, a Nobel Prize–winning economist, put it in 2015, attributable to drugs, alcohol and suicide.

Underlining the mortality rates was economic ruin. Over the last 30 years, wages have stagnated, and the manufacturing sector that fueled the Midwest has been gutted: About a quarter of Americans worked in manufacturing jobs in 1980; as of 2016, just 8.5 percent did. If those jobs have been "replaced," it is with low-wage service work. Meanwhile, two-thirds of the country is without the best ticket out of that economy: a college degree.

The impact of all of this on party identification was striking: In 2007, whites were split, with 44 percent calling themselves Democrats and 44 percent calling themselves Republican, according to the Pew Research Center. But by 2016, the gap had widened to 15 points, with 54 percent identifying as Republican.

Trump, with his pledge to "make America great again," activated the equivalent of a political sleeper cell. Two-thirds of whites without a college education backed the Republican nominee, the largest margin in a presidential election since 1980, although without support from white wealthy Republicans he likely would not have won the election. Not surprisingly, the data finds a strong correlation between "white identity" and support for the candidate in the red MAGA hat. A recent study of whites who had voted for Barack Obama but switched to Trump found high levels of racial hostility and xenophobia; researchers said Democrats' focus during the intervening years on undocumented immigrants and police violence against African-Americans had the effect of "changing perceptions of where many whites feel they belong."

"Whiteness is not invisible now. That is why we are talking about it in ways we didn't for a long time in American history," Jardina says. "Think about the world between the civil rights movement and election of Obama and the way we talked about race. We didn't talk about white people because their dominance and privilege was secure."

Emboldened by Trump's success, GOP candidates staked new outer limits in racial and ethnic messaging in the midterms. Among them: In Indiana, Republican Senate candidate Mike Braun dubbed the incumbent Democrat "Mexico Joe" Donnelly and won. In Tennessee, Republican Marsha Blackburn won after claiming her opponent "lured illegal immigrants" to the state. In the Florida governor's race, Republican nominee Ron DeSantis implored voters not to "monkey this up" by electing Andrew Gillum, who would have been the state's first black chief executive.

Trump's own campaign closed the election with an anti-immigration spot considered so racist that even Fox News took it down. "You know what I am? I'm a nationalist, OK? I'm a nationalist," the president told a boisterous crowd at a rally in Texas. "Nationalist! Use that word! Use that word!" Trump did not use (or left out) the word white.

Democrats, however, fought back. The party nominated a record 180 female candidates in House primaries and 133 people of color. For the first time, white men were a minority in the Democrats' candidate pool. The Democrats primarily ran on health care, education and jobs—as well as Trump resistance—not so much on immigration, even as Republicans stoked fears of the "caravan." The result: Republicans lost 40 seats and their majority in the House. Nearly half of those districts had voted for Trump over Clinton in 2016. Notably, eight were located in the industrial Midwest, the so-called blue wall that fell to the GOP ticket two years ago. Perhaps even more important, Democrats won statewide contests for governor in Michigan and Wisconsin, as well as the Senate in Ohio, in part by cutting in half Republicans' advantage among white men without a college education.

Trump called the midterm results a "tremendous success." Republicans clearly felt the sting anyway. In January, when Representative Steve King set his career on fire by questioning how terms like "white nationalist" and "white supremacist" had "become offensive," GOP leaders quickly condemned his comments. Their action was remarkable, given that they had mostly ignored the Iowa congressman's extensive record of racist statements and dubious associations for more than a decade; just last year, he endorsed a Canadian politician with neo-Nazi ties.

The moral authority fell to Senator Tim Scott of South Carolina, the GOP's lone black member in the Senate. "Some in our party wonder why Republicans are constantly accused of racism," he wrote in The Washington Post. "It is because of our silence when things like this are said."

So diversity is the winner, right? Not so fast.

For all the talk about the Democratic rout, there was no clear message from the midterms. Yes, the new House is historically female and diverse. But in eight white working-class House districts in Minnesota, Pennsylvania and Michigan, where Democrats flipped seats away from Republicans, the winners were all white. Haley Stevens, who worked in the Obama administration on rescuing the auto industry and finding jobs for laid-off workers, took Michigan's 11th from Republicans after half a century. But she soon distanced herself from her progressive colleagues in February, after she was asked about what one voter saw as the anti-Semitism of her pro-Palestinian fellow freshman classmates.

Michigan's 11th and the other seven flipped Midwestern districts are precisely the sort of places Democrats will want to claw back from Trump in 2020. But Democrats now must decide whether they should either write off the white identifiers who hearkened to Trump's racial messaging, or try to win some of them over, as Obama did. Those who think Democrats don't need them look to the rapidly changing populations of states like Arizona, Georgia and Texas. Others see a basic math problem: As much as the country is changing, white working-class voters will still make up nearly half of the electorate in 2020. And they are concentrated in the Midwestern states long considered key to Democratic success.

All this has led to a mostly hushed conversation among Democrats about race and who they should nominate from a crowded and diverse primary field. "I think it better be a white male," said Michael Avenatti, the fleeting White House hopeful and pugnacious lawyer for adult film actress Stormy Daniels in an interview with Time last year. "And I don't say that because I want it to have to be a white male. I say that because of the realities of the situation. If the Democrats nominate anyone other than a white male at the top of the ticket, they're gonna lose the election. I'd be willing to bet anything."

Why? "It's different when you have a white male making the arguments. They carry more weight," he said. "Should they carry more weight? Absolutely not. But do they? Yes."

Avenatti soon bowed out of the race after a domestic violence allegation (he denied it and was not charged by prosecutors), but Senator Bernie Sanders struck a similar chord after the midterms, saying that voters in Florida and Georgia grew uneasy with black Democratic candidates for governor amid the race-baiting attacks from their GOP opponents. "There are a lot of white folks out there who are not necessarily racist who felt uncomfortable for the first time in their lives about whether or not they wanted to vote for an African-American," he told The Daily Beast.

Others were more oblique. "I don't see anyone out there at the moment…the man who can beat Trump or the woman who can beat Trump," white working-class balladeer Bruce Springsteen told The Sunday Times. "You need someone who can speak some of the same language [as Trump]…and the Democrats don't have an obvious, effective presidential candidate."

When former Vice President Joe Biden's supporters suggest that he is the only possible contender who can break through Trump's white wall, they are thinking the same thing. And while Biden hasn't announced it, his inner circle leaked in January that Biden believed he hadn't seen "the candidate who can clearly do what has to be done to win."

This assessment, of course, comes as news to the most diverse slate of candidates the party has ever seen. "It's pretty insulting to white people," Senator Kamala Harris of California told Vanity Fair. "People seem to have a need to fit others into these discrete, neat compartments of their brains. It undervalues the intelligence of the American people. It's really a mistake to assume, based on a person's race or gender, that they only care about certain issues to the exclusion of other issues."

Democrats point out that Obama won two terms in the White House with the help of whites in the industrial Midwest. Then again, 2012 Republican opponent Mitt Romney didn't run a race-based campaign; both candidates largely argued over the economy. With Trump, race is always front and center, as he appeals to voters' sense of white identity, grievance and resentment. He aims immigration at poorer whites as a class-based wedge issue too.

"Wealthy politicians and donors push for open borders while living their lives behind walls, and gates, and guards," Trump said in his State of the Union address. "Meanwhile, working-class Americans are left to pay the price for mass illegal immigration: reduced jobs, lower wages, overburdened schools, hospitals that are so crowded that you can't get in, increased crime and a depleted social safety net."

That talk resonates with voters like Eric Ash, the Democrat turned Republican pastor of Mount Olive Evangelical Lutheran Church in Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania, which is part of a swing congressional district. Like many of the people in the fading steel towns west of Pittsburgh, he voted for Obama in 2008. Later, he changed his registration and cast a ballot for Trump in 2016—mainly, he says, because of his concerns about legal abortion. That support helped give the real estate mogul the kind of lopsided, double-digit margins that won Pennsylvania for him (Romney won Beaver County in 2012, but by only 6.5 points).

"I would say I support the border wall with qualifications," Ash tells Newsweek. "I understand why struggling people want to come here, like my ancestors did 100 years ago. But if we reward people with citizenship who don't follow the law, that rewards law-breaking and penalizes people [following] the letter of the law."

Ash says he doesn't feel a sense of solidarity with other white people, but he knows people in his community who do, and such affinity will affect their voting choice in 2020. "For them, the candidate probably has to be white and male," says Paul, another Beaver County voter who asked that his last name not be used so he could speak freely. "They associate that white male with the prosperity we had in the past." A corporate manager, he voted in 2016 for the Libertarian Party candidate, Gary Johnson, and says he doesn't consider race but he thinks his community does. "Sadly, a lot of people think 'America great again' is Dad goes off to work and Mom is home cooking, and I think it's implied that it is a white family."

But do Democrats even need these voters? Again, the answer is complicated. Political strategist Matt Morrison, the executive director of Working America, the community-organizing arm of the AFL-CIO, has spent much of the past decade trying to figure it out, overseeing interviews with 800,000 white working-class Americans. Like Ashley Jardina in her studies of white identifiers, he divides those who support Trump into two broad camps: The "racial resenters," or true racists, about whose views little can be done. And what he calls "disinterested to disaffected" whites, who may or may not respond to racialized messages but were certainly drawn to Trump's economic ideas. This second group, he says, should be a prime focus for Democrats. "Failure to reach that population means they become kindling wood to the racial resentment messages," says Morrison.

And the Democratic message is as important—if not more important—than the messenger, adds Morrison, who cites Michigan electing a female governor, Gretchen Whitmer, in November with the highest share and total votes of any Democratic gubernatorial candidate in the state in the past decade. Whitmer's campaign slogan, "Fix the damn roads," was the sort of strong kitchen table message that strategists believe can override racialized messaging.

"We cannot be perceived as trying to push coastal or urbanized or different values on people," says Morrison. "But nothing in our experience says you can't go to a white working-class voter and talk about Black Lives Matter and how GM got a giant tax break to shut down the manufacturing supply chain in Ohio. We just need politicians who can hold both thoughts in their heads."

Some point to Ohio's Sherrod Brown, a potential Democratic presidential contender who won a third term in the Senate last year amid a Republican wave in his state. "Democrats don't have to choose between whether we will stand up against racism or fight for an economic agenda that appeals to all workers. We have to do both," Brown tells Newsweek. "And we need to nominate a candidate with a strong record of fighting for workers of all races."

That approach, of framing social justice issues through an economic lens, is the one that Obama took in 2008, when he voiced opposition to reparations for African-Americans. He told the NAACP that while he was concerned with the legacy of slavery and Jim Crow, he was worried that such payments could be used as an "excuse" for government to stop enforcing anti-discrimination laws in employment, housing and education. "I'm much more interested in...how do we get every child to learn?" Obama said. "How do we get every person health care? How do we make sure that everybody has a job? How do we make sure that every senior citizen can retire with dignity and respect?"

In 2016, Clinton and Sanders held similar positions. But the party has since moved to the left, and some leading 2020 contenders are revisiting reparations and other race-conscious proposals, including housing assistance, universal child care and government-funded savings accounts for low-income children. "We have to be honest that people in this country do not start from the same place or have access to the same opportunities," Harris said on the radio show The Breakfast Club. "I'm serious about taking an approach that would change policies and structures and make real investments in black communities."

Democrats, says Princeton's Glaude, are rightly pursuing policies of racial justice and equality. "Because of who I am, I am subject to a particular kind of harm and injury," he says, "and I have to organize around how I am viewed as a way to respond to the specific way I am harmed."

That could rally the progressive base, and there is a wing in the party that believes Democrats can win the presidency without aggrieved whites. Steve Phillips, founder of Democracy in Color, is among the strategists and opinion leaders who argue that a coalition of young Americans, people of color and progressive whites can go it alone. "What Mr. Obama showed twice," he wrote in a New York Times op-ed after the midterms, "is that it works in enough places to win the White House."

Democrats of late are talking about the political bounty of the rapidly changing Sun Belt, but critics note that such a strategy is risky; Obama lost Arizona and Georgia twice and won North Carolina just once, in 2008. Clinton lost all three in 2016.

Meanwhile, Republicans are always eager to use the left's so-called identity politics against them. Like gender-free bathrooms, the issue of reparations is guaranteed to inflame not only conservatives but also white identifiers, who already resent their perceived loss of power. In 2014, a YouGov poll found that half of white Americans believe that slavery is "not a factor at all" in the lower average wealth of blacks; just 6 percent support cash payments to the descendants of slaves.

"If the left is focused on race and identity, and we go with economic nationalism, we can crush the Democrats."

"I want them to talk about racism every day," former Trump strategist Steve Bannon told The American Prospect of Democrats in 2017. "If the left is focused on race and identity, and we go with economic nationalism, we can crush the Democrats."

Of course, the choices aren't mutually exclusive. Trump is also playing to race and identity in a country that, in part thanks to his chosen role as channeler of white male rage, looks more divided by those exact things. According to a new poll from the Public Religion Research Institute and The Atlantic, members of both political parties do see diversity very differently.

Respondents were asked to place themselves on a scale measuring their support of racial and ethnic diversity in the United States. The lowest percentages of Americans from either party agreed with the phrase "I would prefer the U.S. to be a nation primarily made up of people from Western European heritage." But while 65 percent of Democrats agreed with the phrase "I would prefer the U.S. to be a nation made up of people from all over the world," only 29 percent of Republicans felt that way. Instead, about 56 percent of Republicans placed themselves between those two options. Whites were the least likely group to want diversity, with 44 percent preferring the U.S. to be made up of "people from all over the world." Another 42 percent said they wanted something in the middle.

As both parties head into the 2020 campaign, the outcome of the election will reveal which worldview is most American.