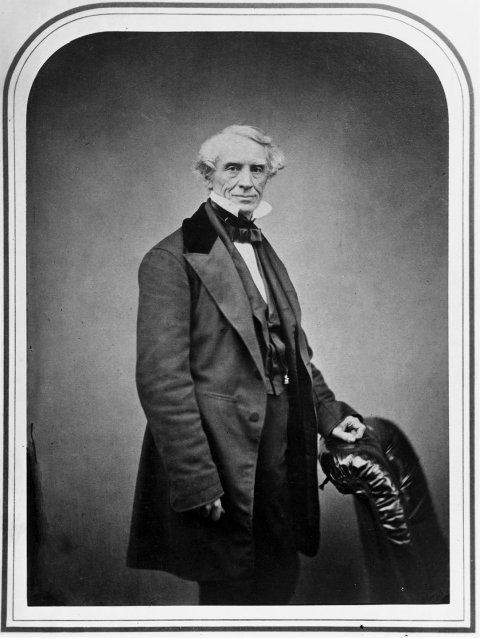

Up! Up! I beseech you…. Shut your gates," said a prominent New Yorker who would soon launch a political career.

A foreign nation, he warned, was sending us "their criminals" because the United States hadn't erected enough "walls" or "gates." The heart of the problem: These new immigrants practiced a religion that was so "despotic" and "ignorant" that it would destroy democracy. He also complained that men like him who had the guts to tell the truth about that dangerous religion were unfairly labeled "bigoted" and "intolerant" by a liberal media that was "on the side of your enemies."

The man was Samuel Morse, then a well-known painter who later helped invent the telegraph and the Morse code. The religion he assailed in 1835 was not Islam but Catholicism. The foreign nation he warned about was not Iran, Syria or Mexico but Austria, which, he believed, was financing the immigration of hundreds of thousands of Catholics to the United States.

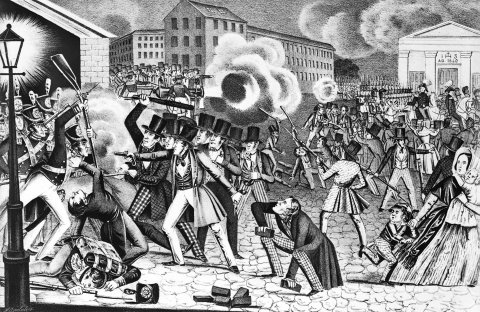

Although Morse was defeated the following year in his run for mayor of New York City, he became an influential figure in the anti-Catholic movement that arose during the period. In the 1830s and 1840s, Protestant mobs burned convents, sacked churches and collected the teeth of deceased nuns as souvenirs during anti-Catholic riots—just one of the many spasms of "anti-papism" that roiled America from the colonial era until well into the 20th century.

Morse's comments are especially jarring because today we have a U.S. president who said Mexico was sending us its "criminals, drug dealers and rapists," claimed "Islam hates us" and persistently blurred the distinction between Islamic terrorists and regular American Muslims. Activists and critics have decried such hostile language, arguing that it can morph into violent acts. By the time of the April shooting at the Chabad synagogue in Poway, California, there was a risk of normalization setting in, as the world had already lived through attacks at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, churches in Sri Lanka, and the Al Noor and Linwood mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand.

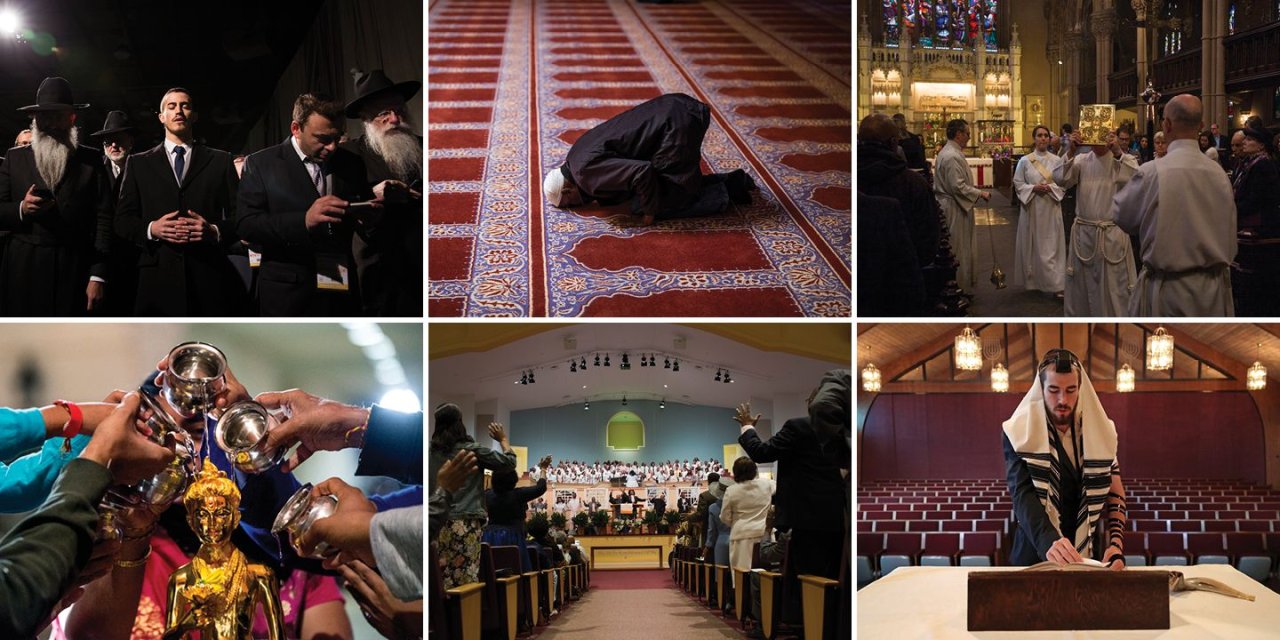

But the Catholic example also is a hopeful one, as it shows how far we've come. Catholics, the largest religious denomination in the United States, have full religious freedom. The single day that best exemplified the dramatic reversal of status was October 5, 2015, when the U.S. Supreme Court began its session by seating six Catholics and three Jews as the justices. In fact, despite recurring controversies, the United States provides a uniquely robust form of religious liberty. Americans have more freedom to organize houses of worship, pray and follow their own spiritual path, unobstructed, than ever before.

The status and nature of religious freedom in America is especially important right now. Until very recently, a strong case could be made that the United States had found a better way—indeed, that America's model of religious freedom is perhaps its greatest invention. It still can be an example for the world, but only if we understand how religious freedom actually developed.

Slow Train Coming

Just as the Declaration of Independence did not suddenly provide African Americans with civil rights, the First Amendment did not magically create religious freedom. It took the sacrifice of ordinary Americans over hundreds of years to build the model.

Despite what we're taught in school, America did not have robust religious freedom for most of its history. The Puritans hanged Quakers from trees in Boston Common for the crime of practicing their faith. In the period right before the American Revolution, half of the evangelical Baptist preachers in Virginia had been imprisoned for their preaching. When the Declaration of Independence was signed, nine of the 13 colonies barred Catholics and Jews from holding office.

The persecution of Mormons was especially brutal. In 1838, the governor of Missouri issued Executive Order 44, calling for the "extermination" of the Mormons. Three days after the order was issued, on October 30, 1838, about 250 Missourians, including a state senator, arrived at Haun's Mill, a small Mormon community, and opened fire. In all, 17 Mormons were killed and 15 wounded.

Perhaps less surprising, hundreds of thousands of Africans were stripped of not only their liberty but also their religions when they were brought to America, in what one historian called "a spiritual holocaust." The vast majority had practiced indigenous African religions or Islam.

After the Civil War, the U.S. government banned many Native American spiritual practices while coercing indigenous children to convert to Christianity. Reformers believed that rather than exterminating the Indians they should push Indian children into schools where they would be taught the ways of the whites—including proper Christian religion. The preferred approach was sending them to boarding schools, away from the reservations. "It is impossible to do anything for these people, or to advance them one single degree until you take their children away," explained Senator George Vest.

And then there were the battles between American Protestants and Catholics, which spanned from the 1600s until the 1960s. In the 19th century, the conflict focused on Protestant insistence that the King James Bible be taught in the public schools. Catholics asked that they be able to read their preferred edition, the Douay-Rheims translation. The Episcopal Recorder explained why non-Catholics could not accept such a proposal: "Are we to yield our personal liberty, our inherited rights, our very Bibles, the special, blessed gift of God to our country, to the will, the ignorance or the wickedness of these hordes of foreigners, subjects of a foreign despot?" In the end, Protestants mostly decided that they'd rather not have the Bible in public schools at all than have the Catholic version given legitimacy.

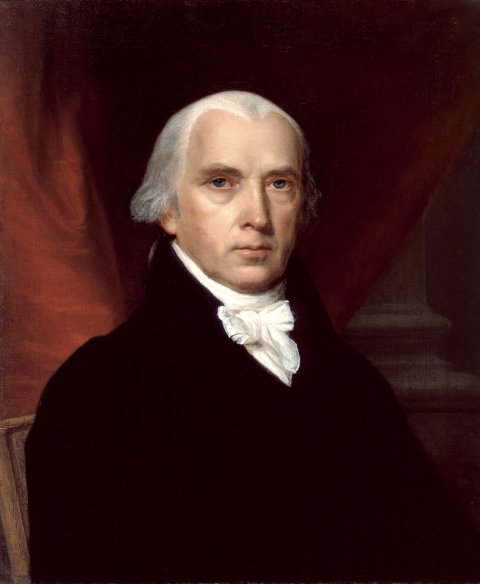

Separation of church and state is not sufficient to create religious freedom, but it did eventually take root, in part because the Founding Fathers had provided a revolutionary new blueprint. The most important draftsman was James Madison. Yes, he did want government to keep away from religion but not to make the nation secular; he thought it would lay the groundwork for religious vibrancy. Looking back decades after the ratification of the First Amendment, he boasted, "The number, the industry, and the morality of the priesthood and the devotion of the people have been manifestly increased by the total separation of the Church from the State."

But, crucially, Madison believed that the surest path to religious liberty would come not from "parchment barriers" (lofty declarations of rights) but rather from a "multiplicity of sects." In a free marketplace of faiths, no one religion would dominate. Spiritual innovation would spread. New styles, denominations and religions would continually emerge, creating still larger constituencies for religious freedom.

No group did more to advance religious freedom than evangelical Christians. We owe our freedoms in part to evangelicals like the Reverend John Waller, who was preaching in Caroline County, Virginia, in 1771 when an Anglican minister strode up to the pulpit and jammed the butt end of a horse whip into Waller's mouth. Waller was dragged outside, where a local sheriff beat him bloody. He spent 113 days in jail for the crime of being a Baptist preacher. These were among 150 major attacks against Baptists in Virginia between 1760 and 1778, many of them carried out by leaders of local Anglican churches—and, significantly, many of them within a horse ride of a young James Madison. "This vexes me the most of any thing," Madison, then 23, complained to his friend William Bradford in 1774. "That diabolical, Hell-conceived principle of persecution rages."

The evangelical leaders fervently advocated for separation of church and state. They believed that both government oppression and government hurt religion, in the first case by squelching freedom of conscience and in the second by making state-supported religion lazy and corrupt. Madison was influenced by the evangelicals' courage, philosophy and votes. It was evangelical voters who elected Madison to Congress—on the condition that he push for religious freedom.

Since Madison's time, immigration has strengthened religious freedom. Waves of foreigners have brought great religious energy and faced tremendous resistance. Protestants attempted to block Catholic immigration in the 19th century. In the 1920s, Congress restricted immigration in part to keep out Jews. The head of the U.S. Consular Service explained that such limits made sense because Polish Jews were "abnormally twisted because of [a] reaction from war strain."

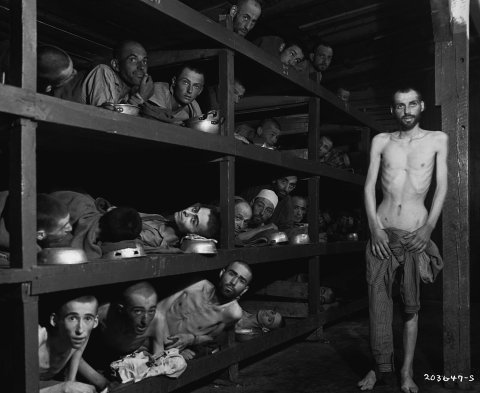

World War II changed everything. The presence of two major existential threats, Fascism and Communism, forced the nation to emphasize the central role that religious liberty played in the American identity. President Franklin Roosevelt took a historic step by declaring religious freedom to be a defining characteristic of American patriotism. He explained that the war preparation efforts were needed to preserve four essential liberties: freedom of speech and expression; freedom from want; freedom from fear; and the "freedom of every person to worship God in his own way—everywhere in the world."

During this period, multifaith squads of clergymen—a minister, a priest and a rabbi—fanned out to military bases around the world. These "tolerance trios" stressed that religious freedom was central to the democratic system the troops were defending. After one such event, a member of the National Conference of Christians and Jews reported, "The three speakers...had those 36,000 men on their feet cheering, applauding, whistling, yelling—one of the most tremendous ovations I have ever seen given to men in my life." By the war's end, trios had spoken to more than 9 million Americans at 778 bases.

After World War II ended, American leaders worked to convince a war-weary nation that they remained in a cosmic battle—now against Communism. As the Soviet Union consolidated power in Eastern Europe, it suppressed local religions and promoted an aggressive atheism. President Harry Truman explained the Cold War as follows: "We are defending the right to worship God—each as he sees fit according to his own conscience."

After the war, the news about the Holocaust and then the creation of Israel further sensitized Americans to anti-Semitism. The Ad Council ran a public service campaign from 1946 to 1952 called "United America." A typical print ad featured an illustration of a bird hanging up a sign reading, "No Catholics, Jews, Protestants," prompting another bird to scold, "Only silly humans do that!"

It was during the Dwight Eisenhower administration that Congress added the phrase "under God" to the Pledge of Allegiance and "In God We Trust" to our paper currency. But Eisenhower made a point of combining this new public piety with an equally strong call for pluralism: "Our form of government has no sense unless it is founded in a deeply felt religious faith, and I don't care what it is. With us, of course, it is the Judeo-Christian concept, but it must be a religion that all men are created equal."

An 'Accommodation' Revolution

For most of American history, religious freedom meant you couldn't explicitly persecute people for their religion. But that left another question: What if secular laws end up violating a person's religious belief inadvertently? In the 19th century, the Supreme Court had a clear position: tough luck. In the 20th century, it became more nuanced.

A landmark case in 1963 involved Adele Sherbert, a textile worker in Beaumont Mills, South Carolina. The factory that employed her instituted a six-day workweek—Monday through Saturday. But Sherbert was a Seventh-Day Adventist, which teaches that the Sabbath is Saturday. She quit and applied for unemployment benefits but was rejected on the grounds that she had left her original job voluntarily and turned down opportunities to work at other factories (which also required work on Saturdays). The state of South Carolina had a reasonable position. The law didn't target Seventh-Day Adventists; the state was blind as to whether it hurt or helped a particular religion.

But on June 17, 1963, the Supreme Court ruled 7–2 in favor of Sherbert, saying the state could infringe upon someone's religious practice only if there is a "compelling state interest" and no other regulation could be conjured to achieve that same goal. Otherwise, the state must "accommodate" the person's religious practice. In other words, the state had to bend over backward to avoid making a religious person choose between the law and his or her faith.

This fundamentally transformed the nature of religious liberty. No longer would it be defined only as the absence of intentional persecution. The ideal would now be something more expansive—a system that grants people tremendous space in which to live their faith, even when that conflicts with laws that other people have to abide by. When religious conservatives challenged the Affordable Care Act's requirement that health plans offer contraception, they used this theory. The Catholic plaintiffs didn't claim that the contraception provision intentionally targeted Catholics or evangelicals. Rather, they said their rights had been infringed as an unacceptable side effect.

Freedom Is Fragile

The American approach does not rely only on constitutions, laws and regulations. It's a dynamic system that ensures its own perpetual self-improvement. Over the decades, a virtuous circle has developed. Religious liberty allowed for more sects, and those minority faiths in turn demanded more freedom. Thanks to that forward motion, government's role changed from promoting religion to promoting religious freedom.

But while the American model of religious freedom has come a long way in recent years, it has shown fragility.

The worst attack on Jews in American history took place not in 1918 but in 2018, at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, where 11 died. Of the 1,679 religiously based hate crimes catalogued in 2017 by the FBI, 58 percent were against Jews and 19 percent against Muslims. And the attacks on American Muslims are as troubling as any we've seen in about 70 years. Ugly messages once thought to be purged from public discussion have reappeared. For instance, those opposed to Mormons and Catholics in earlier years had claimed that those were not really legitimate religions. So it was ominous when, in 2007, Christian televangelist Pat Robertson said, "Ladies and gentlemen, we have to recognize that Islam is not a religion. It is a worldwide political movement bent on domination of the world. And it is meant to subjugate all people under Islamic law."

Michael Flynn, President Donald Trump's former national security adviser, declared that "Islam is a political ideology. It definitely hides behind being a religion." Retired Lieutenant General William Boykin, an anti-Islam activist, explained that because Islam is "a totalitarian way of life, it should not be protected under the First Amendment."

In the months after 9/11, President George W. Bush defended American Muslims, but soon after, conservative Christian leaders started taking a different tack. Franklin Graham in 2002 called Islam a "wicked, violent religion." Jerry Vines, the former head of the Southern Baptist Convention—the sect that had led the charge for religious freedom in the 18th century—called Muhammad a "demon-possessed pedophile."

Verbal attacks morphed into concrete assaults on Muslims' religious freedom—including one of the most basic, the freedom to establish houses of worship. In 2012, the Pew Research Center's Forum on Religion and Public Life counted at least 53 instances of proposals for mosque construction or expansion being contested by local residents. When the Islamic Society of Milwaukee applied for permission to build a mosque, a rally was held to protest "the growing threat of Islam," with one resident claiming that "a mosque is a Trojan Horse in a community. Muslims have not come to integrate but to dominate." From 2010 to 2016, the Justice Department joined or initiated 17 cases in which, it believed, opposition to mosque construction violated the religious freedom of American Muslims. In Culpeper County, Virginia—the same county where Baptists had been persecuted in Madison's time—the Justice Department argued that the town denied approval of a mosque despite having previously granted similar permits for churches on 26 other occasions.

Conservative media embraced the anti-Muslim cause. Radio personality Michael Savage opined, "They say, 'Oh, there's a billion [Muslims]. I said, 'So, kill 100 million of them, then there'd be 900 million of them.' I mean...would you rather us die than them?" Rush Limbaugh asserted that Islam was "not even a religion."

Fox host Jeanine Pirro targeted respected Muslims who had participated in interfaith religious ceremonies. "Muslims were even invited to worship at the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C.," she said. "They have conquered us through immigration. They have conquered us through interfaith dialogue."

While criticizing President Barack Obama for offering praise for Islam's achievements, Fox commentator Andrea Tantaros shifted seamlessly between terrorists and Islam in general: "They've been doing this for hundreds and hundreds of years. If you study the history of Islam, our ship captains were getting murdered…. You can't solve it with a dialogue. You can't solve it with a summit. You solve it with a bullet to the head."

Social media have exacerbated the problem. These platforms don't create hate, but they certainly psychologically incentivize it. On Facebook, a member of the conservation commission of Easton, Massachusetts, posted a photo of a mushroom cloud with the headline "Dealing With Muslims...Rules of Engagement." The Minnesota Republican Party posted a photo of Keith Ellison, then a Minnesota state representative and a Muslim, on its Facebook page under the headline "Minnesota's Head Muslim Goat Humper." And a county commissioner in Mifflin County, Pennsylvania, posted an image of a mosque with a red "no" symbol slashed through it and the headline "No Islam Allowed."

Meanwhile, during the 2016 campaign, Trump proposed banning immigration by Muslims and creating a special registry to help track Muslims. Asked if he would consider warrantless searches on mosques and Muslims, he said, "We're going to have to do certain things that were frankly unthinkable a year ago."

Public opinion about Muslims, which had been worsening for a decade, darkened as the 2016 election approached. The percentage of Republicans who said at least half of the Muslims living in the United States were anti-American jumped from 47 percent in 2002 to 63 percent in 2016. (In the same poll, 92 percent of Muslims said they were "proud to be an American.") In one poll, only half of Republicans were willing to declare that Islam should be legal in America.

A Role for Evangelicals

How do we preserve America's model of religious freedom in the face of these challenges?

Different faith groups must cultivate a heartier all-for-one, one-for-all solidarity around religious freedom. We have seen this develop between American Muslims and Jews, who have stepped up to support one another in the aftermath of attacks. We now also need to see American evangelicals fight against harassment of American Muslims instead of joining it. In fact, few things would better safeguard religious freedom than if American evangelicals regained their leadership position on the matter—adopting the posture of their ancestors who helped develop our national model. The key is viewing religious freedom not only as a way of advancing the position of one's own religion but also as the cause of liberty more generally.

Though we don't have to love our neighbors, Americans should feel morally obliged to understand them. In each generation, toxic generalizations have been applied at the expense of religious minorities and religious liberty in general. Baptists were ignorant. Catholics were disloyal. Jews were greedy. Mormons were lowlifes. Jehovah's Witnesses were un-American. Christians are bigots. Muslims are terrorists. Public officials and religious leaders who, for political or financial reasons, attempt to sow religious division should be recognized for what they are: opponents of religious freedom.

Secularists need to compromise as well. Nonbelievers benefit when believers are protected. Most of the worst persecution of atheists around the world comes in countries that also harass and imprison religious minorities. Religious people need the freedom not only to worship privately but also to express themselves publicly and to associate with like-minded Americans. Just as mainstream Christians had to accept the unorthodox views of Jehovah's Witnesses and Mormons, secular Americans cannot attempt to criminalize religious beliefs they find repugnant.

We have come a long way. Most of our modern fights over religious freedom are minor skirmishes compared with the battles that were fought earlier. We should appreciate our unusual achievement and what our ancestors had to sacrifice. Let's not squander it. Indeed, as the world becomes more interconnected, America has something great to offer: a paradigm for how religious difference—so often the source of violent division—can be harnessed or even turned into strength.

John Winthrop thought America would be a city upon a hill because it would show how purified religion could create a righteous society. Going forward, our status as that inspiring model may come not from religion alone but from religious freedom.

In the future, the world can benefit from what America has learned, if we manage not to forget it ourselves.

This is adapted from Sacred Liberty: America's Long, Bloody and Ongoing Struggle for Religious Freedom by Steven Waldman.