In 2020, during the greatest public health emergency in 100 years, General Mark Milley, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said about the COVID pandemic, "We are at war. It's a different type of war, but a war, nonetheless."

Battling a pandemic is a special kind of war. Pandemics are not just a public health crisis. Like more traditional wars, they affect every aspect of life and society and demand decisive leadership at the top.

The Trump White House struggled to understand this, and our country suffered extensively as a result. In 2018, President Trump abolished the relevant National Security Council Directorate for Biosecurity, the office that I founded in 1998 during the Bill Clinton administration and expanded under President George W. Bush. Trump's action dissolved any semblance of a permanent integrated response command structure at the White House for dealing with biothreats and pandemics. His timing, given the events that followed, was devastating.

Then, when the pandemic struck, President Trump decided that the war against COVID-19 didn't need to be led by a trained combatant commander, someone whose sole professional mission is to prepare for and lead a whole-of-government response to biologic threats—an approach that creates a shared vision, secures coordination and cooperation across federal departments and agencies and implements the response under a single commander. Instead of a competent U.S. operation equipped to fight this nontraditional enemy, we found ourselves confronting election politics and science denial. The administration ignored the lessons of the past influenza and Ebola epidemics and the work of at least three previous administrations, resulting in a disjointed and disastrous response.

Without cohesive national leadership, governors, local public health authorities and longtime federal civil servants from a variety of agencies, including the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), had to step in to stem the chaos and piece together rational strategies. In a normal battle, that would be like asking the majors and sergeants to plan the campaign strategy while engaged in a tactical firefight on the ground.

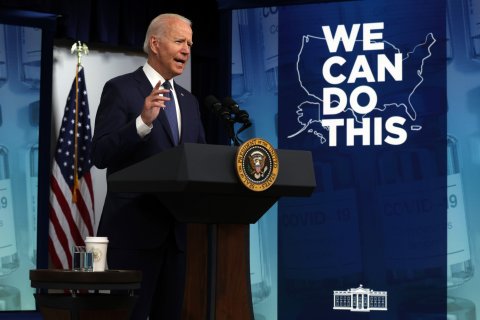

With President Biden, the pandemic response is now in the hands of highly competent leadership at the White House. Andy Slavitt, who served as a senior adviser on COVID response, and Jeff Zients, who succeeded Deborah Birx as the White House Coronavirus Response Coordinator, among others, aggressively pursued a whole-of-government approach and helped rehabilitate our national response to COVID-19. But their leadership, and much of the ad hoc COVID-19 organization at the White House, is temporary—it could disappear after the pandemic recedes, much like what happened in 2015 when current White House Chief of Staff Ron Klain's brilliant leadership as White House Ebola Response Coordinator was abolished after the Ebola epidemic waned. Slavitt, in fact, already left his position, exiting in June.

How can we avoid the need to create a new leadership structure every time we are confronted with a new biologic threat? It is critical that we redesign our national command, control and operational structures and capabilities to deal with the next pandemic or other serious biothreat. To do so, we can look to the part of the government that routinely plans for other conflicts and wars: the U.S. Department of Defense.

During the Vietnam war and subsequent military deployments, the DOD struggled with issues of inadequate and cumbersome command structure, unclear objectives and inconsistent planning and readiness. Congress responded by enacting the 1986 Goldwater-Nichols Defense Reorganization Act. This historic piece of legislation is a model for repairing our broken civilian biothreat command structure.

The Goldwater-Nichols Act made the most sweeping changes in the U.S. military since the DOD was created in 1947. The legislation rocked the siloed command structures of the Army, Air Force, Navy and Marines, long entrenched with interservice rivalries that had contributed to operational and tactical mishaps not only in Vietnam, but also during the 1980 Iranian hostage crisis, the 1983 invasion of Grenada and the 1983 suicide bomber attack on the U.S. Marine barracks in Lebanon.

The Goldwater-Nichols Act redesigned how the military services work together at strategic and operational levels. On the strategic side, it unified the chain of command under the Combatant Commanders—11 commands with broad continuing missions based on region (for example, U.S. European Command) or function (for example, Special Forces)—improved the efficiency of operations and prioritized joint mission requirements over the needs and interests of individual services. Its utility was proven in Panama in 1989 and the Persian Gulf war in 1991.

On the operational side, our military Joint Staff is tasked with developing Operational Plans (OPLANS) and playbooks to fight and win wars. Such advance planning enables a rapid, coordinated and successful response in the event of a national security threat.

Our public health preparedness and response to biologic threats and pandemics need a similar and fundamental reorganization. This military blueprint is adaptable for a civilian command structure for our preparedness and response to the inevitable next pandemic or major biologic threat.

President Biden has taken some initial first steps. On Day One of his administration, he recreated an office and appointed a Senior Director for Global Health Security and Biodefense at the National Security Council. However, I believe he needs to go further.

The NSC position should be elevated to the rank of Deputy Assistant to the President and have clear authority over the entire biosecurity portfolio, creating the civilian equivalent of a Combatant Commander. Their sole mission should be to prepare for and lead the government response to biothreats, both naturally occurring and intentionally caused. The office should develop and exercise OPLANS, coordinate academic and private sector partnerships and, most importantly, remain in place to plan for future biologic threats. In addition, it should have rapid response and operational authority to guide our response to future threats.

This responsibility cannot be downgraded to an agency. Neither the CDC nor NIH are capable of fulfilling the role of leader for a large-scale government pandemic response. Their culture and normative responsibilities are not well suited for command-and-control operations. The Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response in the Department of Health and Human Services has previously attempted to assume this responsibility, but other departments such as State and Defense are neither required, nor even inclined, to follow the HHS lead. The White House NSC is the only executive branch institution that can adequately corral the disparate mission interests of the departments and agencies.

Congress will also need to prioritize both departmental authorizations and coordinated appropriations for what is inherently a crosscutting interagency operational responsibility for national biosecurity preparedness and response.

We also need to attract the brightest and the finest into a biosecurity career path within the government by incentivizing promotion and career advancement for those working in an interagency biosecurity role, from departments such as State, Defense, Treasury, intelligence agencies and the traditional public health sector such as the CDC and NIH.

The Goldwater-Nichols Act did as much for the military by making joint staff assignments a requirement for promotion to admiral or general. Before Goldwater-Nichols, joint command assignments were often not viewed as career advancing, much as biosecurity assignments have often been career-killers in the national security community.

As never before, we are acutely aware how important national biodefense leadership is to save lives and protect the economy. COVID-19 isn't going away soon, and the next biologic threat—one that is perhaps even more deadly—is just around the corner.

Kenneth Bernard, M.D. is a retired U.S. Public Health Service Rear Admiral and former Assistant Surgeon General who worked on biosecurity in both the Bill Clinton and George W. Bush administrations.