Award-winning foreign correspondent David Loyn spent years in Afghanistan learning about the Taliban. He was there when they took Kabul for the first time in 1996 and has been there consistently since. In his new book The Long War (St. Martin's Press), Loyn analyzes the U.S. involvement from the start and what went wrong. He talks to the generals and gets the inside scoop. In this Q&A, Loyn discusses what early decisions set the course for America's longest war, which administrations handled it best, whether anyone foresaw the rapid takeover by the Taliban in August and the future of U.S.-Afghan relations.

At what point did the U.S. military mission in Afghanistan become unwinnable? Was it always, or was there a point that sealed its fate?

In the first week of December 2001, two decisions of the Bush administration set the course for what would become America's longest war. On December 3, U.S. special forces began an assault on the Tora Bora caves where Osama bin Laden was holed up. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld wanted Afghans to do the ground fighting and paid unreliable local militias, backed by U.S. air power, and a handful of special operators. This was despite 1,000 Marines on the ground near Kandahar, and 3,500 more not far away on board a ship. Bin Laden escaped. Not only was this a failure to pursue the main target of the war, but the decision to shower millions of dollars onto these and other militias fueled corruption from the beginning, and obstructed a functioning state. Later that week, on December 5, the Taliban offered to surrender to the newly appointed interim leader, Hamid Karzai. Rumsfeld turned it down, so the Taliban leaders fled to Pakistan to regroup.

Which of the last four administrations do you feel understood Afghanistan the best, and for which president could the same be said?

President Trump's withdrawal deal in 2020 was terrible because it gave nothing to the Afghan government, while demanding they release Taliban prisoners and accept the departure of international troops. But the Trump administration was full of real talent and people who understood Afghanistan, and until the deal, things were going in the right direction. The Obama administration never had a coherent stance, but a series of competing policies that he arbitrated. Hard to say who was the best president on this. Bush had real commitment, but many missteps happened in his time.

In your book you say that Biden has consistently advocated for fewer troops on the ground. Had Obama listened to his generals instead and increased the U.S. presence in 2009, do you think that could have made a lasting difference?

The key was not just troop numbers but a will to commit. There was never any long-term planning; every year was Year One. And Obama reduced the impact of the surge by announcing a departure timetable at the same time. The constant desire for an exit strategy paradoxically prolonged the intervention.

By the time President Biden inherited the conflict, was there anything else he could have done that might have significantly altered the course of the fighting, or the nation-building project, in Afghanistan?

Biden did not have to stick to the withdrawal timetable. The Taliban had not negotiated in good faith, so there was a reason to scrap the Trump deal. By the time Biden came into office, U.S. troops were at a low level, not engaged in combat on the ground, and only around one third of the international total, which included troops from Germany, Italy, Turkey and U.K. None of these countries was consulted in the decision to pull out. This has left a lot of bad feeling in NATO.

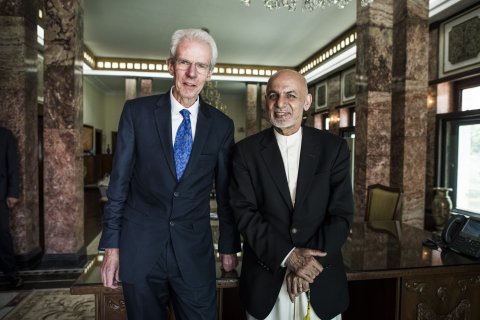

Many were stunned by the Taliban's rapid takeover of Afghanistan, and especially Kabul, over recent weeks. What were the underlying causes of the collapse of the Afghan President Ashraf Ghani's government and its security forces?

The government felt remote, so soldiers were less likely to defend it. And corruption had hollowed out the armed forces. By one estimate there were not the supposed 300,000 troops, but only 50,000. Once morale began to collapse, the army was overtaken by what the former Afghanistan and Iraq commander General David Petraeus called "an epidemic of surrender." The speed of collapse of Kabul on August 15 surprised even the Taliban who were not ready for it.

There has been a lot of reflection lately over U.S. shortsightedness throughout the conflict. Do you feel the Taliban, based on their words and actions, have learned lessons that contribute to their success, both tactically and diplomatically?

In tactical terms, the Taliban have always been highly adaptable, and backed by Pakistan have turned into a more effective fighting force. In diplomatic terms, they are very different from the past, with a sophisticated propaganda machine in five languages. They will be judged though on deeds not words.

The Taliban now say they want to have peaceful relations with all countries and are "committed to the rights of women within the framework of Sharia." What does this really mean for women and girls in the country today who have lived dramatically more free lives for the last two decades?

There was Sharia in Afghanistan until now. President Ghani led a government operating under Sharia law, but the Taliban want something far more restrictive. The way they interpret the Hanafi school means that rights and opportunities, particularly for women, and in the cultural arena, will be significantly curtailed. A sad sight this week was seeing instruments at the Kabul music school smashed by their own students as they did not want to be found with them by the Taliban.

What do you foresee, based on current events, for the future of U.S.-Afghan relations? Do you feel the country might continue to be a priority for U.S. assistance, might it drift more into the fold of China and Russia as they seek new opportunities in the absence of U.S. forces there?

The U.S. has no cards left, but no option but to seek engagement, because of the volatility of nuclear-armed Pakistan, now emboldened by the all-out Taliban victory. China and Russia have received assurances that the Taliban will not export militants to their countries, which will be difficult to enforce.