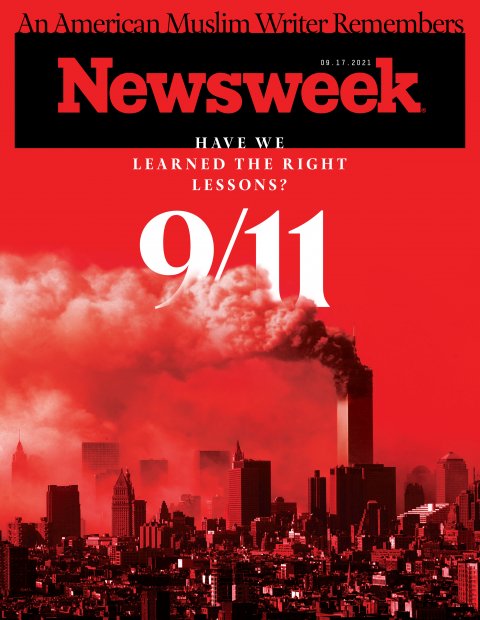

Two decades after the attacks on 9/11, the death and injury toll is still climbing, due to the large number of people exposed to a toxic cloud of contaminants and dust in lower Manhattan after the Twin Towers fell. Yet only a fraction of the estimated 500,000 already ill or at risk of becoming sick are receiving treatment through the federal health programs set up to help them or have gotten financial support from the massive government fund that compensates 9/11 victims.

More than 3,900 people have already died as a result of 9/11-related conditions, surpassing the 3,030 people who were killed directly in the attacks by Al-Qaeda 20 years ago, federal statistics show—a number that experts say will inevitably rise as more people who breasted in toxins after the Twin Towers collapsed develop and succumb to illness. An additional 112,000 are currently being treated for various medical conditions—including serious respiratory disorders and different types of cancer—related to their exposure to what's been described as a "witch's brew" of more than 2,500 contaminants in downtown Manhattan on 9/11 and in the days and months that followed.

Meanwhile, the federal 9/11 Victims Compensation Fund (VCF), which provides financial support, has received nearly 67,500 claims, paying out a total of $8.95 billion to date.

Those numbers, as staggering as they are, suggest there are potentially hundreds of thousands of victims who are going untreated and who aren't getting the financial compensation they are entitled to, given the estimate of half a million people exposed to 9/11 toxins by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which administers the World Trade Center Health Program.

"It's heartbreaking to know that there are these benefits available and people aren't taking advantage of them," says Michael Barasch, a New York City attorney whose office was blocks from the World Trade Center on 9/11. He developed prostate cancer, was awarded compensation through the VCF (which he donated to charity) and has since represented tens of thousands of other victims who were exposed to the 9/11 toxic cloud that day.

First responders and volunteers searching for survivors on "The Pile"—the 1.8 million tons of twisted and burning wreckage where the north and south towers of the World Trade Center once stood—make up the lion's share of those seeking treatment as well as a majority of those who have submitted financial claims to the VCF so far. Of the 100,000 or so people believed to have served as responders, around 80 percent have enrolled in the WTC Health Program.

But less than 10 percent of the estimated 400,000 civilians thought to have been exposed have done the same. Those potential missing victims include lower Manhattan residents, office workers around the World Trade Center, children who went to school in the area, family members searching for the missing and visitors paying their respects.

Some have already died; others will never get sick. Some will become ill, but won't apply for support from either program.

"We were all breathing the same toxic dust, we're all coming down with the same illnesses," says Barasch, who notes that the most common reason affected civilians don't apply for health or financial benefits is that they don't know that they're eligible. He has spent years urging people with potential exposure to gather proof of the time they spent in the WTC zone, such as signed affidavits from friends and colleagues, pictures and videos, or work and school attendance records.

"God forbid, if you get sick in 10, 20, 40 years, you're going to need that proof," Barasch says. "Every year that goes by, it's going to be harder and harder for the 9/11 community to prove that they were exposed."

The Fight for Ongoing Support

That first responders and civilians with 9/11-related illnesses are still able to get medical care and financial compensation via federal programs 20 years later is a relatively recent development, won after years of political battles. The original Victims Compensation Fund, established by Congress 11 days after the attacks and targeted specifically to those injured and the families of those killed in the immediate aftermath, closed in 2004.

"It was a one-off program designed to respond to an unparalleled American tragedy, a unique response to a unique American catastrophe," says attorney Kenneth Feinberg, who oversaw the first iteration of the fund and whose struggle to convince victims' families to sign on is depicted in the new Netflix film Worth.

Although some families were initially reluctant to participate—for example those who didn't want to sign away their rights to sue the airlines, others argued with the formula for determining financial awards—ultimately 97 percent of eligible families submitted claims and over $7 billion was dispensed. The median award: $1.6 million.

In the end, says Feinberg, "The fund was an unqualified success."

But while that was largely true for families whose loved ones were injured or killed on 9/11 or in the days immediately after, the narrow window of eligibility for funds from the original VCF left out those doing recovery and cleanup work who suffered injuries more than four days after the attacks or who later became ill from breathing in the toxic fumes around the World Trade Center site. One of them was John Feal, a demolition supervisor who was injured during Ground Zero cleanup efforts and eventually had one foot partially amputated. He was initially denied compensation as his injury occurred just outside the initial 96-hour window of eligibility.

"At the time, devastating," Feal tells Newsweek of his claim's rejection. "At the time, insulting. At the time, it made me want to hate the world. But looking back, it's one of the things that made me who I am today."

Feal began organizing with other responders who were injured or fell sick after their work in the exposure zone, becoming a leader in a community of advocates pushing for the fund to be reopened and to establish a health program for those with 9/11-related illnesses. Working closely with Feal was Richard Palmer Jr., a deputy warden in command for the New York City Department of Correction, who was working out of the department headquarters six blocks from the World Trade Center when the first plane hit.

Palmer and his colleagues helped secure the area and evacuate civilians, then assisted in the recovery effort after both towers came down, setting up a temporary morgue outside Bellevue Hospital and operating out of the command center established at a nearby high school. Later, they also raked through toxic debris that had been transported to a local landfill, looking for human remains and helping to identify victims.

"We didn't lose anybody on that day, but we've lost 24 officers to 9/11 illnesses since then," Palmer tells Newsweek. Palmer himself had to undergo a quadruple bypass at age 43 and has also developed severe asthma.

Feal and Palmer were joined by many other first responders who traveled frequently to Washington, D.C. in the years following the closure of the first VCF fund, lobbying for legislation to help those who continued to suffer health problems as a result of 9/11. Many of those with them were on the verge of death from their illnesses, Palmer notes.

"They knew there were thousands of individuals in this country that still needed help," Palmer says. "We wanted to make sure they were taken care of, and their families were taken care of for the future."

After a protracted political battle, the Zadroga Act—named for New York Police Department officer James Zadroga, who in 2006 died from an illness related to his exposure to toxic materials in the aftermath of 9/11—passed in 2010. The legislation reopened the VCF, extended the claims deadline and provided limited additional funding for five years. It also expanded the VCF's eligibility to include anyone who spent time in the "Exposure Zone"—broadly south of Canal Street and west of Clinton Street in lower Manhattan, as well as any areas along the debris removal routes including barges and the Fresh Kills landfill site in the New York City borough of Staten Island.

In addition, the legislation created the WTC Health Program, which provides monitoring and treatment for 9/11-related conditions and can certify such illnesses for a VCF claim. Those registered with the WTC Health Program are not necessarily eligible for VCF compensation, but are eligible for monitoring and treatment for related conditions. It is open to anyone who can prove they spent time south of Houston Street in Manhattan, or on any block in Brooklyn contained within a 1.5-mile radius of the former World Trade Center site.

The Zadroga Act was reauthorized for another five years in 2015, increasing VCF funding to $7.375 billion, extending the claims filing deadline yet again and re-authorizing the WTC Health Program until 2090. When it became clear the fund would run dry before its expiration date, advocates pushed for permanent authorization. This was won in 2019, extending the claims filing deadline to 2090 and automatically appropriating all funds necessary to pay eligible claims.

Throughout the fight, Feal and his team were supported by comedian Jon Stewart. Stewart's emotional rebuke of the "callous indifference and rank hypocrisy" of Congress in 2019 on behalf of 9/11 first responders was the climactic moment of the campaign.

"They responded in five seconds, they did their jobs with courage, grace, tenacity, humility," Stewart told lawmakers. "Eighteen years later, do yours."

Feal was seated just behind Stewart during the session. "What he did was the most amazing thing I've ever witnessed," Feal says. "He articulated our pain and suffering. He let America know what we'd been through the last 18 years."

A Bittersweet Victory

As the 20th anniversary of 9/11 approaches, Ann Van Hine is reflecting on her decision not to accept compensation from the original VCF. Her firefighter husband, Bruce, died with five other members of Bronx/Harlem Squad 41 while trying to save people in the south tower, but she didn't want to sign away her right to sue back then and felt she'd be okay financially, relying on her widow's pension from the city.

She has no regrets about not taking the money herself but says she was glad to see the VCF extended and expanded so others could be compensated. "I think that is only proper," she says. "We're still realizing the ramifications of what happened that day."

Palmer agrees, expressing concern that the toxic cloud will be killing people long after he and his fellow first responders are gone. "Anybody who was young that went to school down there—and there were a lot of young kids going to school down there—they're in their 30s, and they're sick now from breathing that shit in."

The 9/11 responders "won," but no legislative victory, however impressive, can turn back the clock. "There's no amount of money in the world that's going to bring my foot back," Feal says. "There's no amount of money that's going to offset the pain and suffering I've been through."

The 2021 remembrance, he hopes, is a chance to soothe America's rancid partisan divide. "I pray that, just like on 9/11, we will put aside our differences," Feal says. "I know we're capable of putting aside our differences—whether it's for 10 minutes, or an hour, or the whole day—remembering those who we lost, remembering who we continue to lose."

He also worries that another event like 9/11 will inevitably happen again—and hopes that America is prepared. Says Feal, "Wishful thinking, gullible, naive me prays that we're prepared not only for that event, but also, this time, to take care of those who run into harm's way. Because this country has an odd way of repeating its mistakes."

Correction September 10, 2021 11:55 a.m. ET: This story has been updated to reflect that Robert Palmer Jr. worked for the New York City Department of Correction on September 11, not the New York State Department, and to clarify the location of the temporary morgue and command center where he and his colleagues worked on 9/11.