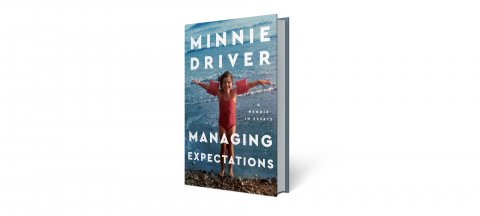

Academy-award nominated actress Minnie Driver shares the ups and downs of her life through entertaining and poignant tales in her book Managing Expectations—ranging from her first solo sung on the local news in a windy tree at her English boarding school to the death of her beloved mother during COVID-19, with candid stories of many acting failures and successes in between. Driver describes her son Henry's birth—a surprise from start to finish—in this excerpt from her memoir. Henry was the happy result of a brief relationship with writer Timothy J. Lea when they were working together on The Riches, and Driver has raised her son as a single parent since his birth in 2008. And through it all, Driver explores the beauty of managing her way through the unexpected and painful to find joy.

"I think you're pregnant," my sister, Kate, said.

"No."

"I think you are."

"But I've got a difficult uterus, remember that horrible old doctor comparing it to having a U-bend in a toilet and said I'd never get pregnant."

"F**k that guy. Let's get a pregnancy test."

Even through the profound fear of what this might mean, a keen wonder was also present as I peed on the two sticks. I then sat on the edge of the bath and waved the sticks like Polaroids. My mind was now blank, it was clear, it was unmoving; my whole life, past and present, had come to a gliding halt as one of two potential futures prepared to join the caravan. I looked down at the sticks, and the two sets of parallel lines that told me I wasn't alone in the bathroom. I stood up and looked at my face in the mirror, and I smiled. That was the very first acknowledgment of my baby, an instant human reaction to joy, our first salutation.

One day at an ultrasound the doctor said:

"So, do you want to know if it's a girl or a boy?"

"No, thanks."

"Okay." He paused and kept ultrasounding, clicking on the computer keyboard, taking measurements.

"Well, she is really big and beautiful," he said, smiling.

"I...I didn't want to know the sex," I spluttered.

"Oh, goodness, did I let that slip? Oh I am so sorry."

Apologies were not enough to stop me bursting into tears. I didn't want some guy ripping off the baby from having its first introduction; it wasn't his news to tell. I was upset enough that the doctor wrote in large red letters on my file:

"DO NOT MENTION GENDER"—as if not repeating that I was having a girl would help me unhear the fact. Consequently I couldn't help holding only the idea that I was having a girl, but it was never mentioned again by anyone.

I had loosely been calling my daughter "Bel." I liked the brevity of the name and the clear syllable it sounded out. I imagined her small and freckled with a shock of dark hair, wrists with folds of sweet chub, and one blue eye, one brown eye, like my father. I imagined quietly encouraging her to feel safe on whatever ground she stood and teaching her that shifts in terrain had no bearing on how she could choose to feel. She was this tiny, fluid warrior who smiled and cried with her whole heart, then shook it off like an Etch A Sketch and began anew.

I labored for a night and a day and another night, longing to meet her. On the first night, my sister came into my bedroom, which was filled with candles and the stereo sound of soothing monks om-ing, and she said,

"Are we having a baby or a f**king séance?"

Mum asked if I fancied spaghetti Bolognese.

My friend Isla, the former child actor (turned rave pro), had now become a doula and midwife. She'd come down from Northern California to help me have a home birth and at this point in the proceedings told me to tune out the sounds and just focus on my breathing.

"Which sounds? The om-ing monks?"

"More the spaghetti."

"Okay, okay, but ow, my God, this really hurts."

"All good, all good, you just gotta turn your OW into WOW!"

I sort of wished my sister had been present to hear this.

It turned out my baby was enormous, in general and more pertinently in relation to its exit point, but I still believed the unlikely union between my sturdy Anglo-Saxon heritage and a yogified Hollywood pelvis could deliver this baby into the giant tank of water that stood at the end of my bed. At hour35, the midwife from my doctor's surgery had shown up, taken my pulse and blood pressure and announced that the baby was fine, but my heart rate was tired and slow, and it was time to go to the hospital.

"What about the water tank?" I wailed between contractions.

"That's done, darling," said my mother. "This is now."

We arrived at the hospital, and I was given pain relief that can only be described as orgasmic.

"You don't know how bad the pain is until it's gone, huh?" said my doctor, who had just turned up.

"No. SHE KNOWS/I KNOW," said my sister and I in unison.

"Are you ready to push?" he said amicably. It was the second 4:45 a.m. of being in labor—I was so ready.

I had a welcoming playlist I wanted to be playing as the baby was born. The soothing monks were there, and some whale song was mixed in with deep cuts from Johnny "Guitar" Watson and Stan Getz. I told the expectant crowd that I wanted "love" to be the first word the baby heard when she was born, so for 45 minutes I screeched and panted "LOVE!" in a very active meditation.

"LOVE!" I screamed as the head was born.

"Love, LOVE!" To the shoulders and the arms.

"LOOOOVVVVE!" as the baby fully emerged.

"IT'S A BOY," said my mother. To which I responded,

"WHAT THE F**K?????"

The baby wailed, clearly having been woken from a nice dream, with a bad word, my very first parenting choice already trashed with an expletive. They laid him on my chest; he was long and very red and had an extremely pointy cranium, like a baby Dan Aykroyd in Coneheads. He was alien and astonishing, and I could only stare at him in silence and experience the next thing a mother must learn to accept (after she's said the wrong thing): nobody had told me that the very first thing we do as mothers—the thing we are asked to continue doing again and again in our children's life—is to let go. I was also letting go of my conceptual daughter, the idea/person I had been bonding with for the past 5 months. Was she there in him? I was suddenly overwhelmed by a strange grief that perhaps I would never know her, and a guilt that this baby here on my chest had arrived into the world a stranger, because I had been busy thinking they were someone else. I wonder why I had become so attached to the gender of my child in the first place? I think it was benignly narcissistic (if such a thing exists). Perhaps, more kindly, it was primal. Being a single mother, thinking I would be raising this baby by myself, the thought of her being a girl—a reflection I had already seen, one I knew and could speak to—felt reassuring; as if, as a neophyte parent, there was at least one thing I understood; as if her gender were my choice anyway.

I looked at my mother, at Isla, and at my friend Tiffany, who had also been part of the strange intense ritual of the past few days.

"He doesn't even have a name. I didn't do any boys' names because he was 'Bel.'" I started to cry, and the nurse came over and said, why didn't I give her the baby so I could have a cup of tea and move out of the delivery room and into a clean bed.

"NO," I said.

"We are not moving anything until this baby has a name. You have to have a name. To start. You have to have a name. Even if they change it later, I've got to give this baby that, right now. Please?" I looked at all my women, all of them completely exhausted but understanding that this had turned out to be the final push.

"Kai."

"Dakota."

"Miles."

"Stone," said the helpful voices.

I looked at them.

"HE IS NOT A CONTESTANT ON SURVIVOR."

Then, like a bell ringing out, Tiffany said,

"Henry."

Immediately, as a chiming chorus, everyone said his name,

"Henry, Henry, Henry."

I looked down at the baby, tiny and gigantic at the same time, the culmination of all the love I had ever felt or dreamed of, the person who had suddenly given me tenure for life, and who I knew would bring their own luck.

"Hello, Henry, thank goodness you're here."

Excerpt from Managing Expectations: A Memoir in Essays by Minnie Driver. Published by HarperOne. Copyright © 2022 HarperCollins.