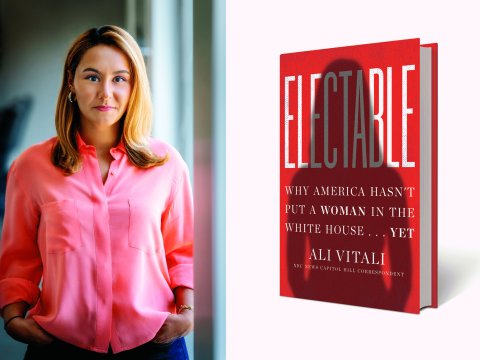

NBC News Correspondent Ali Vitali was embedded with Elizabeth Warren's campaign during her 2020 bid for the White House. She then took over coverage of Kamala Harris on the Biden-Harris ticket. Vitali's reporting raised the question in her mind, "why haven't [we] had a female president, after a race that saw more women run than ever before"? Vitali seeks to answer that question in her new book, Electable (Dey Street Books). In the following Q&A, Vitali discusses the lessons she learned from Warren's campaign, whether reports of trouble in Harris' office spells difficulty for her future election prospects, if 2024 will finally be the year a woman will be elected president and much more.

What's the most important factor at play for voters deciding if a woman is a viable candidate?

Everyone wants to back the candidate (man or woman) who can win—which is why "electability" is such an important metric...and why the way gender factors into how it's assessed is so important. Understanding the biases at play, and how they've manifested in recent election cycles for female candidates, is the work of this book so that we can disrupt those trends in real time going forward, leveling the playing field for candidates of both genders.

Women in positions of power walk a fine line—being forceful without being called bitchy, for example. What will it take to hold men and women to the same standards?

I think often about the ways reporters ask female candidates if they think they're "likable enough" or "can a woman win." It immediately puts them on defense and frames the question in a negative way—something male candidates don't face. Imagine asking a man, "are you likable enough to win?" or "can a man win this election?" Maybe we should [ask men the same questions]. That would level the playing field, while also showing the absurdity of some of these moments. But, of course, the counter is a woman just winning—showing once and for all that they can—and eroding the premise of the question entirely.

Has the #MeToo movement had an impact on the electability of female politicians? In what ways?

The #MeToo moment showcased the strength and fortitude of women willing to come forward, so in that way, it held women up as positive examples against the backdrop of men behaving badly. But at the same time, those women faced powerful blowback. And we still rely on women to call out the bad behavior of men and hold them accountable in ways that we don't always ask men to. The Al Franken example is a good one. Reporters looked first to the women of the Senate for answers on it, and when Senator Kirsten Gillibrand was a leading voice in saying he should resign—a position that most of her Democratic colleagues also took—she was dogged by that choice for months during her presidential campaign and negatively tagged for politicking and betraying a friend.

How can women close the fundraising gap?

For donors, it's about return on investment. The more women run and win, the more their winning ability proves the point; 2018 was a reminder for Democrats that women candidates were the face of a massive electoral wave in the House, and 2020 was that wake-up call for Republicans. Women must be invested in if parties want to win.

Should a candidate be evaluated on his or her gender at all?

Candidates show up how they show up. We're meant to take them in as a full package—politics and persona—so, of course, gender is going to be a factor. And it should be. The diversity of opinion that stems from different lived experiences, genders, races, socioeconomic or geographic backgrounds having seats at powerful policy-making tables and pulling the levers of government allows for more American experiences to be represented and reflected in government. That's good for everyone.

You were embedded with Elizabeth Warren's presidential campaign. What lessons did you personally take from her exit from the race? What can future candidates learn?

The fact that she left the race and was so direct about the gendered cross winds that impacted her was an indelible moment for me—and should be for women candidates and voters broadly going forward. Even though she was leaving the race, it was incredibly powerful and, frankly, validating to hear a candidate speak about gender's role in the presidential political process. It forced the public to, again, grapple with a systemic problem. It wasn't just Elizabeth Dole or Hillary Clinton. Warren was viable—as were [Amy] Klobuchar and Gillibrand and Kamala Harris, and Clinton and Dole, etc. before her—as a presidential contender. There were political reasons that she didn't win, and I detail those, but there were also those intangibles that she made tangible by voicing them. That matters. Once you see the inequities in the system, it's harder to stop seeing them. And it hopefully means next time, they'll be easier to call out and strategize around. Every woman who runs makes the ground firmer for those who come after them.

It was reported that Harris' presidential campaign had difficulties beyond gender or race; there was talk of divisiveness and poor treatment among her staff and policy inconsistencies. As VP, there has been regular turnover among her staff. Do these issues spell trouble for her?

They could. These issues are certainly something she'll have to explain should she run to succeed Joe Biden, in large part because they're part of a pattern. There was relatively high turnover in her Senate office, then her 2020 presidential campaign, and now in her vice presidential office, which marks a trend for Harris—one that any other politician, man or woman, in her roles would have to answer for. But, as has been true her entire time in the political spotlight, her margin for error in answering and explaining these questions is less than a male counterpart and she will likely be given less benefit of the doubt by voters (and, possibly, media) when she ventures to give those explanations.

Will 2024 be the year the U.S. elects a female president?

Hillary Clinton is one of many people who told me "I'd love to see it in my lifetime." To which I replied, that I'd love to be able to stop saying that. It's entirely possible 2024 is the year we can retire the phrase because—assuming Biden and Trump aren't the standard bearers yet again—there are multiple viable female candidates on both the Republican and Democratic sides ready to run. The more cycles that we see that, the fuller the pipeline gets, the closer and closer we get to making history.