For most Lord of the Rings trilogy fans, hobbits are the portly folk of Middle-earth who live in homes carved out of hillsides in "the Shire'' and spend their lives smoking pipe-weed, singing songs and drinking ale. But some influential real-life people see hobbit life in J.R.R. Tolkien's Middle-earth—free from government intervention and overreach—as close to societal perfection.

Paypal co-founder and early Trump ally Peter Thiel, for instance, spent his teenage years reading and rereading The Lord of the Rings. Palantir Technologies, the multibillion dollar data mining and surveillance firm he cofounded, gets its name from "palantiri": indestructible "seeing stones" in Tolkien's books; its Palo Alto offices are known informally as "the Shire." Other Thiel companies have Tolkien-inspired names like Valar Ventures and Rivendell One LLC.

Andy Ellis, an information security expert at the cloud security firm Orca Security and himself a lifelong Tolkien fan, says, "I've always thought Palantir was the most foolish name for a company." In Tolkien's books, the palantiri corrupt nearly all who use them. When the good wizard Saruman uses one to spy on the peoples of Middle-Earth, he is drawn in by its power and ensnared by the Dark Lord Sauron, who uses the seeing stone to get the wise man to serve him.

Thiel's Palantir has a similarly double-edged reputation. Amnesty International, for instance, says U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) used Palantir technology to track undocumented migrant workers and plan raids that led to the separation of children from their parents. When Amnesty International inquired about the company's partnership with U.S. immigration authorities in 2020, Palantir's director of privacy and civil liberties said ICE's use of its products "raises legitimate and important questions for us about our complicity in activities that, while lawful, may nonetheless conflict with norms and values that many of us hold."

Matt Mahmoudi, an adviser on artificial intelligence and human rights at Amnesty International, says the firm's mass-surveillance projects and the lack of transparency around them, represent "a slippery slope toward the erosion of basic freedoms." Palantir did not respond to a request for comment.

Billionaire Palmer Luckey, founder of the virtual reality company Oculus (known for its headsets), also named a company after a powerful artifact of Middle-earth: Andúril, a sword made from the shards of a weapon that defeated the Dark Lord.

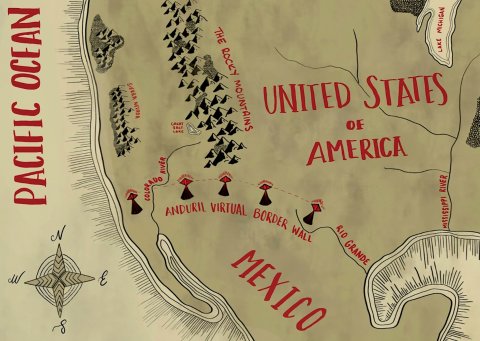

Luckey's Anduril Industries makes artificial intelligence-focused defense technology for customers like the U.S. Department of Defense and the Department of Homeland Security. Thiel's Founders Fund was an early investor.

Under the Trump Administration, the company began building surveillance towers along the U.S.-Mexico border that track undocumented immigrant crossings using object recognition. Computer scientists and human rights groups say virtual border wall projects like Anduril's have increased migrant death rates by pushing people toward less monitored, more hostile terrain.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection has described the towers as partners that never sleep or blink. To Tolkien fans, that description might conjure up images of Sauron's fiery, ocular watchtower rather than the weapon used to defeat his evil forces.

World Building

Admiration for Tolkien is more rule than exception in some parts of the tech industry, according to Orca Security's Ellis. "Tolkien was one of the few things geeks had in common growing up, so it was easy to make references to it," he says. The shared cultural language gave entrepreneurs a reservoir of references to bond over. It also allowed tech world-builders to piggyback off one of the English language's most prolific world-builders. For Thiel and Luckey, using Middle-earth terminology is not some whimsical literary exercise. It is a nod to the libertarian philosophy they perceive in Tolkien's world.

Patrick James, professor of international relations at the University of Southern California and author of The International Relations of Middle-earth: Learning from The Lord of the Rings (University of Michigan Press, 2012), an analysis of real-world geopolitics through the lens of Tolkien, says nearly any ideological group can find something to latch onto in the books.

What do conservative libertarians find so appealing about them? "No government tells the free peoples [elves, men, dwarves and the sentient-tree people called Ents] what to do," James says. "There really isn't much government at all." When crisis comes to Middle-earth, good people willingly share resources without explicit government mandates. Public investment largely goes toward defense, so when foreign hordes invade, there are usually enough swords and shields for willing fighters to take up arms against them. Charismatic leaders usually rise to the top thanks to their heroism and overcome immense hardship to fulfill their destinies.

In a 1943 letter to his son, however, Tolkien outlined his own political opinions at the time as leaning "more and more to Anarchy," but emphasized he meant "abolition of control, not whiskered men with bombs."

Make the Shire Great Again

American tech moguls aren't the only conservatives with deep admiration for Middle-earth. Italy's recently elected hard-right Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni may be the most devout Tolkienite to ever hold elected office. As a teenager in 1993, Meloni spent time at "Camp Hobbit," an Italian political fantasy retreat for the country's far right. On her personal webpage from the '90s, she called herself "Khy-ri the Undernet Dragon" and wrote that The Lord of the Rings is "of course," her favorite book.

In a conversation with The New York Times last year, Meloni outlined what she saw as antiglobalization messages in The Lord of the Rings. Meloni pointed to the fact that each of Tolkien's races benefit from the "value of specificity," meaning they had particular cultures and identities that were worth preserving. She extended the same logic to the people of Europe's sovereign nations. Italians—like hobbits and elves and dwarves—are unique and should protect against anything that threatens their identity, she suggests.

James points to another plotline from which Meloni may have taken inspiration. At the end of the trilogy, the quartet of hobbits from the Fellowship return to the Shire to find their idyll overrun by Saruman and his henchmen, who have turned the once-bucolic countryside into an industrialized wasteland and enslaved its residents. "To someone like Meloni with a romanticized sense of the past," James says, "it's easy to say 'Look at The Lord of the Rings. It was so much better once upon a time. Rapid changes came, others began intruding and everything got worse.'"

"I think that Tolkien could say better than us what conservatives believe in," Meloni told the Times.

Tolkien himself, though, didn't intend to inject any politics into Middle-earth. In a forward written for the 1965 edition of the trilogy, he wrote: "As for any inner meaning or 'message,' it has in the intention of the author none."

"The prime motive was the desire of a tale-teller to try his hand at a really long story that would hold the attention of readers, amuse them, delight them, and at times maybe excite them or deeply move them."

As James puts it, "What you see in Lord of the Rings says more about you than it does about the storyline."

This story is co-published with Capital & Main