I knew a guy in college who could consume heaping bowls of ice cream without any discernable effect on his six-pack abs. I've been wondering ever since why my body doesn't respond that way to my favorite dessert—or, for that matter, if I'll ever find one that I won't regret the next day when I step on the scale. Recent advances in nutrition science now are edging closer to delivering on my dream of dessert with impunity—and a lot of other health benefits, besides.

It's long been obvious, to scientists and lay people alike, that each person responds differently to a given food or diet regimen. For years, scientists have tried to figure out how to accommodate these idiosyncrasies in a way that improves health and avoids common ailments such as heart disease, obesity and diabetes—and, for better or worse, helps people lose weight.

After years of trying to find genes that might account for individual differences, scientists have come to realize that genes alone cannot explain the human body's relationship to food in all its complexity. Diet and health involve genes and many other factors besides, including sleep, exercise, stress and other lifestyle matters. One of the biggest factors—perhaps the biggest—is the community of trillions of individual microorganisms that live in each person's gut, called the microbiome.

This news is good because, while you can't change your genes, you can cultivate healthy gut bacteria, change the timing of meals and adjust diet and lifestyle factors to optimize metabolic health.

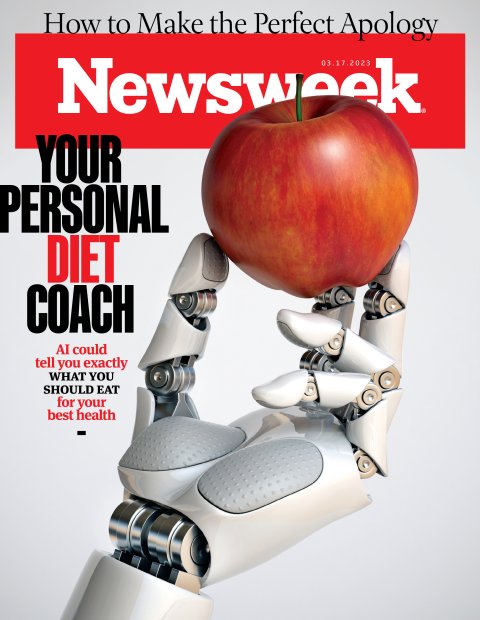

It would also be a data nightmare, if it weren't for recent advances in artificial intelligence—in particular, a type of AI called machine learning, which can recognize patterns in mind-boggling amounts of data. AI can digest all the measurements required to assess the state of each individual's health and use them to generate helpful insights, including predictions about how food choices impact wellness and risk for disease.

The goal of this science is to arrive at a long- promised era of personalized nutrition, with potentially profound effects on human health. Last year, the U.S. National Institutes of Health announced plans to dole out more than $170 million in research grants to speed the development of new algorithms that predict individual responses to food and dietary routines. The agency is gearing up to recruit and enroll 10,000 Americans in a study that will track their daily diets, feed some of them special diets selected by researchers, carefully track individual responses and then use some of these algorithms to analyze them. The study will take into account an individual's genetics, gut microbes and other lifestyle, biological, environmental or social factors, "to help each individual develop eating recommendations that improve overall health."

A bevy of startup companies are incorporating the results of recent studies into new health products. They offer self-administered tests and machine-learning assessments of an individual's diet predilections and recommendations on how to adjust diet and lifestyle to stay healthy and fend off disease. But here's the rub: The interplay of diet and metabolism over many individuals in a population is so complex that scientists need much more data before they can take into account all aspects of human health. Some companies offer helpful advice, but it's not clear if it's always better than what you can get from your doctor during a routine checkup.

The new nutrition science comes not a moment too soon. Rates of diabetes, obesity and preventable diseases linked to metabolic disorders have reached unprecedented levels, and continue to rise. About 9 percent of Americans are already diabetic. An additional 33 percent of Americans are prediabetic, meaning their bodies are already profoundly dysregulated and can no longer properly control the amount of sugar circulating in the blood. Between 2017 and 2020, the prevalence of obesity (defined as a body mass of 30 or higher) increased from 30.5 percent to almost 42 percent—placing millions at far higher risk of developing metabolic syndrome.

Personalized nutrition, some say, is our best chance of getting those numbers down. Whether this new approach will be able to lift the U.S. out of its public health crisis is an open question.

Trillions of Gut Microbes

A few weeks ago, I requested a kit from a Boston-based nutrition startup called Zoe that purports to measure the way my body responds to different foods and generate recommendations on how I might adjust my diet to suit my unique metabolic profile. A while later, I received a canary-yellow package a little bigger than a shoebox containing two packets of vanilla muffins, larded with enough fat and sugar to send a small animal into a hyperglycemic frenzy.

The purpose of the muffins is to "challenge" my metabolism, so Zoe's scientists and AI algorithms could compare my body's response to those of 70,000 other hopeful dieters who have previously undergone the testing. To measure this, along with my response to a host of additional metabolic challenges and tests, the muffins came with an assortment of gadgets—a continuous-blood glucose monitor that looked like a giant thumbtack, an at-home blood test and an elaborate "stool collection kit" complete with disposable gloves and a tiny plastic spoon. After taking all these tests, the company promises to send a detailed report and action plan—along with an early preview of the future of health care.

The founder of Zoe is Dr. Tim Spector, a 64-year old "genetic epidemiologist" at Kings College London, and the author of several books on the science of nutrition. In 2017, a pair of internet entrepreneurs with machine learning backgrounds, Jonathan Wolf and George Hadjigeorgiou, heard him give a lecture at the National Geographic Society in London on nutrition. Afterwards, the two engineers buttonholed him with the idea of putting his words into action. The three formed Zoe soon after, emerging from "stealth mode" in 2020 after raising millions of dollars in venture capital. They launched a slick marketing campaign pegged to the publication of a pair of high-profile, peer-reveiwed papers in the prestigious scientific journal Nature Medicine.

If you'd asked Spector 20 years ago why different individuals respond in different ways to identical diets, he probably would have delivered a lecture on genetics. He had, after all, spent the previous 20 years building the U.K.'s largest registry of identical and fraternal twins so he could study how genes influence human health and disease. Originally trained as a rheumatologist, Spector's work included influential findings on how genetic variations might influence differences in the way individuals metabolized vitamin D, which plays a key role in the uptake of calcium, bone health and the severity of some forms of arthritis. Like most of his colleagues, he believed we were on the cusp of a revolution in personalized nutrition that would be powered by new genetic sequencing technologies. He has recruited 13,000 twins to participate in studies with the idea of making this revolution happen.

By the early 2010s, Spector's opinion—and that of many of his colleagues—had begun to change. He had fully sequenced the genomes (three billion bits of genetic data encoded in each individual's DNA) of about 3,500 twins in his registry. The results were disheartening. Many of the conditions that had produced promising initial data suggesting they might be linked to specific genes using less precise genetics tests showed only modest genetics associations when analyzed with the better tools. For instance, the influence of genetics on the age at death, he recalls, was only about 25 percent. For heart disease it was roughly 30 percent.

In the realm of nutrition—a growing area of personal interest to Spector who, in 2011, had suffered a minor stroke and resolved to change his diet—the influence was even harder to find. In rheumatoid arthritis, the disease in which his previous vitamin D research had generated so much optimism, genetics turned out to account for less than 15 percent of the risk. In obesity, he'd found a thousand associated genes. They explained, he says, less than 1 percent of the variation among individuals.

"It became quite obvious to me that we couldn't predict common diseases this way for most people," he says. "And that was also true for traits like nutrition, including differences in the way individuals metabolized fats and carbohydrates."

Luckily, there were promising new places to look. In the late aughts and early 2010s, Jeffrey Gordon, a fellow geneticist at Washington University in St. Louis, demonstrated that some obese individuals had abnormally low levels of certain kinds of gut bacteria compared to lean individuals, and that it was possible to reverse these ratios through diet. Inspired by this finding, Spector, like many of his colleagues, began to dabble in studies examining the gut microbiome, and its possible links to metabolic disorders and other diseases.

In 2015, another crucial piece of the puzzle fell into place. An Israeli research group at the Weizmann Institute of Science published a bombshell scientific paper in the journal Cell that called into question one of the most widely used tools in the field of nutrition—"the glycemic index," a rating system that measured the length of time it took for the human body to convert the natural carbohydrates in a given food into glucose and release it into the bloodstream. The index, based on readings collected and averaged from a small group of test subjects in the 1970s and early 1980s, had for decades been a central measure used to evaluate the nutritional qualities of food. Foods with a high glycemic index were thought to lead to unhealthy spikes in blood glucose levels, which, over time, were associated with a greater risk of developing diabetes and a whole host of other metabolic conditions.

The Weizmann scientists repeated the experiment on 800 healthy individuals and, armed with all the implements of modern science, did so in far greater depth and rigor. The team followed each individual for a week, recording blood sugar levels using a continuous glucose monitor every five minutes, eventually characterizing individualized responses to a total of 46,898 meals.

The results were shocking. For one thing, the researchers demonstrated wide variability in individual responses to each of the meals, casting doubt on the utility of the widely used glycemic index. And they demonstrated a far more effective way to evaluate the nutritional qualities of food: by using a machine-learning algorithm to find patterns in large amounts of nutrition data. Their algorithm was able to predict the glycemic response of different individuals to specific meals with far more accuracy than the glycemic index by analyzing individual response to previous meals, measurements of physical activity, the amount of fiber consumed over the previous 24 hours and the presence of 72 distinct kinds of bacteria in the gut.

The implications for human health and preventative medicine were potentially profound. Now there was a powerful way to measure a host of important metabolic processes in each individual and come up with ways of modifying them. The problem had a solution.

"There are 20,000 human genes that characterize who we are, which are of course extremely important but cannot be changed," says Eran Elinav, a Israeli gastroenterologist turned research scientist who was one of the senior authors on the paper. "You cannot change a gene that predisposes you to cancer. But the microbiome represents a hundred-fold more genes to our human body—close to 3 million genes on top of the 20,000 genes that are coming from the human side. And these genes are much more amenable to manipulation than the human genes. You can change it simply by changing the composition of the microbiome."

Burgeoning Crisis

The finding had big implications for public health. The United States is currently in the grips of a crisis caused by surging rates of "metabolic syndrome," a cluster of conditions that occur when the systems the human body relies upon to transform food into the energy, and regulate the amount of glucose in the blood, begin to break down. The symptoms of metabolic syndrome include chronically high blood sugar, excess fat, high cholesterol and triglyceride levels and increased blood pressure. And it is associated with diseases such as heart disease, stroke, osteoporosis, certain types of cancer and type 2 diabetes.

Public health experts are optimistic that precision nutrition can help get the problem under control by minimizing unwanted blood glucose spikes and other factors associated with disease. Glucose comes from the carbohydrates we consume, which are broken down in the digestive system and released into the bloodstream. Though essential to powering the normal processes of the human body, too much glucose in the bloodstream for too long has been linked to unhealthy levels of chronic inflammation. When the human metabolic system is properly functioning, the amount of circulating glucose is carefully controlled by the release of a stew of different hormones involved in digestion, hunger and metabolism.

The body, however, can only process so much glucose at once. Too much glucose in the blood stream can kick off a self-perpetuating biochemical cascade that short-circuits the system. The muscles and the liver, which would normally absorb the glucose, reach their limit, causing glucose in the bloodstream to rise. The pancreas responds by flooding the bloodstream with more insulin, the signal that tells cells to absorb the glucose. In response, cells in the muscles and liver, which are normally primed to respond to insulin, become less sensitive to the signal, which means the pancreas must produce larger and larger amounts of insulin to get their attention.

Eventually, excess glucose causes chronic inflammation and interacts with free-floating proteins and fats to cause "glycation," a chemical reaction that damages these cells, stiffens blood vessel walls and leads to high blood pressure, diabetes and strokes. Without the ability to efficiently convert glucose into the energy we need, we grow lethargic and fatigued. Even though our bloodstream is already awash in fuel, we grow hungry for more food. We eat more, move less and the downward spiral continues.

This process has already played out in millions of people. An estimated 43 percent of Americans are already diabetic or prediabetic, which means their metabolisms are profoundly dysregulated and can no longer properly regulate the levels of sugar in their blood. Two out of three Americans are overweight, placing them at risk of developing the disorder. The medical cost of obesity in the U.S. tops $173 million a year.

"Glucose control causes diabetes and diabetes rates have skyrocketed in recent years," says Michael Snyder, chair of genetics and director of genomics and personalized medicine at Stanford University and the former director of the Yale Center for Genomics and Proteomics. "It's far more prevalent as an endemic than COVID was a pandemic. So getting glucose under control is a big, big deal."

Research that has emerged since the Weizmann paper suggests that glucose control is only one of many areas that could be modulated with a better understanding of the factors that influence individual responses to different foods. Other research suggests the microbiome and other factors can influence our ability to absorb specific nutrients, metabolize fats and a wide array of other factors. Over the last decade, researchers have identified scores of specific species of gut bacteria, studied and characterized their impact and published the results in top peer-reviewed scientific journals. They've also demonstrated that these bacteria can help break food down in the intestines and transform them into nutrients, chemical messengers and other beneficial metabolites that the body on its own would be far less likely to absorb.

They have also discovered "bad" microbes that produce unwanted byproducts detrimental to metabolic health. Some of these, research suggests, can have a profound impact on essential metabolic processes. Recently, for instance, researchers at Emory University identified an "obesity-promoting" chemical produced by intestinal bacteria called "delta-valerobetaine" that seems to interfere with the liver's capacity to oxidize fatty acids and burn fat during periods of fasting. Obese individuals, with BMIs above 30, the researchers found, had levels of delta-valerobetaine in their blood that were about 40 percent higher than others. Perhaps most significantly, the research suggested a specific nutrient often found in animal products like red meat, and available as a dietary supplement, might help counteract the effect.

Startup Fever

This research has spawned scores of consumer products from companies hoping to capitalize on the excitement. (These include a company cofounded by Elinav and some of his collaborators on the Cell paper, known as DayTwo.) Over the last decade, the number of firms offering personalized nutritional testing and advice has grown from less than 20 to almost 700 today, according to Mariette Abrahams, the CEO and founder of the consulting firm Qina, which tracks the "personalized nutrition industry," which is estimated to top $8 billion.

The depth and relevance of the testing offered by these companies varies widely, as does the usefulness of the information they provide. Some rely on detailed questionaries, or data collected by sleep and activity trackers. Others collect and analyze blood, urine, hair and stool samples and then feed the results into proprietary AI algorithms that spit out dietary and lifestyle advice and recommendations. Some still rely on outdated genetic tests that likely do not have much utility.

Since Zoe's testing is based on techniques it used to produce the data cited in studies it published in highly respected journal Nature Medicine, it is considered by scientists in the field to be among the more credible of the bunch (though plenty of researchers have questioned whether the field has matured enough to justify the cost of paying for the products). It offers consumers a toned-down version of the protocols used in a pair of scientific studies, known as the PREDICT and PREDICT 2, done in collaboration with academics at Harvard, Stanford and a wide array of other institutions. The studies, published in Nature Medicine in 2019 and 2020, used machine learning to analyze genetic, microbiome and blood samples collected from 1,000 twins and unrelated healthy adults as they consumed a series of identical meals—including the muffins I received in my yellow box. It factored in data about sleep, exercise, stress and other environmental factors. Then it teased out the relative influence each of these factors had on individual differences.

Like others before it, the study, considered one of the most comprehensive examinations to date of individualized responses to food, found wide variations in the way its participants responded to the meals. But the most headline-worthy takeaway—particularly given Spector's pedigree—was that the vast majority of these differences were due to modifiable non-genetic factors, such as the microbiome or lifestyle choices.

"We found a 10- to 15-fold difference in blood sugar and fat levels for individuals fed the same meal at the same time," Spector tells Newsweek. "But less than 30 percent of the variation in glucose spikes was due to your genes. For fat, that number was less than 5 percent. That's when we really threw genes out the window. I had to suddenly stop thinking I was a geneticist anymore and changed to being more of a microbiome nutritionist."

Snyder, whose firm, January AI, sells its own consumer tests, says that his company's proprietary artificial intelligence algorithms have been trained on the reactions of different individuals to a wide array of different foods and that these reactions are highly predictive of how these individuals will respond to other kinds of foods with similar macronutrient profiles. Thus, after collecting data on the way an individual responds to just four days-worth of meals by tracking glucose levels with a blood sugar monitor, Snyder says, his company's algorithm is capable of making accurate predictions about the way that an individual will respond to most other foods.

"If we know that certain foods spike you and others don't, we can make accurate predictions about how you will respond even without necessarily knowing and understanding all the underlying causes," he says. "We have a 32 million food database. I'm not saying it's perfect, but it's pretty good. "

With this knowledge, Snyder notes, it may be possible to minimize sugar spikes in the bloodstream. That might be done by substituting some foods, or by first eating other foods that interact with one's individual metabolism in ways that are likely to help suppress those spikes, attenuating the effects of foods likely to cause big spikes—like that ice cream I'm hoping to consume with impunity.

Missing Pieces

Whether commercial products like Zoe, January AI and others offer enough benefit to justify their costs remains a matter of some debate. None have gone through the rigorous testing required to win FDA approval, meaning the agency has determined the benefits of the product outweigh the known and potential risks.

Spector's Zoe, Elinav's DayTwo, and Snyder's January AI are based on peer-reviewed research produced by recognized leaders in the emerging field of personalized nutrition. On the plus side, their services offer interesting insights on how specific foods affect blood sugar. Although most American diabetics already know all about continuous glucose monitors, their use by non-diabetics only emerged over the last five years, says Snyder.

The science behind microbiome analysis is promising. Zoe tests for the presence of 15 "good" microbes and 15 "bad" ones and recommends a series of specific foods to boost the good ones and suppress the bad ones. They claim their own research has found that those who use their products have more energy, are less hungry, sleep better and have an easier time maintaining a healthy weight.

Coaching is another benefit. After a $300 testing program that includes wearing a blood glucose monitor for two weeks and analysis of stool, Zoe offers access to the firm's searchable food database, which uses an AI algorithm to assign scores to individual foods based on the way a client's blood sugar and fat levels responded to the muffin test and other tests. It costs an additional $30 per month.

For those who already avoid processed foods and eat a Mediterranean diet, however, it's not clear that commercial tests offer enough useful information to be worth paying for.

Like any computer program, algorithms are only as good the available data. A great deal remains to be learned about precisely what factors contribute to individual differences in metabolism, scientists say, beyond what commercial testing offers. For all the variables that scientists have some understanding of—such as genetics, the microbiome, sleep and exercise patterns—a dizzying number of other variables interact in ways scientists are only beginning to understand. These include the effects of age, menopause, the precise composition of food, previous meals, stress, meal timing, overall fiber intake and overnight fasting.

Scientists are only beginning to figure out the microbiome. Many more gut microbes remain to be discovered—and the number of those deemed to be important has increased since the original PREDICT study. Scientists also know little about how an individual's immune systems interacts with the microbiome and the food we eat.

"Eventually we will get to the point where certain dietary recommendations at the individual level will be useful, but we're not there yet," says Eric Topol, director and founder of Scripps Research Translational Institute. "There's a lot of promise here. But it's complicated and there's a lot of layers of data and no one has yet cracked the case. No one has yet done the multimodal AI to understand how all these interact."

Based on its current trajectory, the science will likely continue to improve. Evidence is growing, for instance, that the unique characteristics of each person's immune system, shaped by past exposures to pathogens, plays a role in metabolic differences. In one recent experiment, Synder and his colleagues found the consumption of an Ensure shake, a leading nutrition drink that includes protein, vitamins and minerals, caused an anti-inflammatory response in some individuals (which is good) and a pro-inflammatory response in others (which is usually not good). In another recent study, Snyder showed that some types of fiber lowered the cholesterol of some individuals and helped them metabolize glucose, while in others those same fibers caused inflammation, the release of a specific liver enzymes, bloating and flatulence. The results suggest that, in some cases, one-size-fits-all nutritional guidelines could lead some people to adopt diets that are not good for them.

Inspired by Snyder, I consumed several pints of Ben and Jerry's ice cream under a variety of different conditions, and discovered that eating certain high-fiber foods prior to stuffing my face with ice cream seemed to attenuate my blood sugar spikes. Still, even if I got my metabolism working to perfection, 1000 calories of ice cream is still a lot to handle. It seems unlikely I'll ever find a way to eat ice cream while rocking washboard abs. But I'm optimistic about what I might learn.