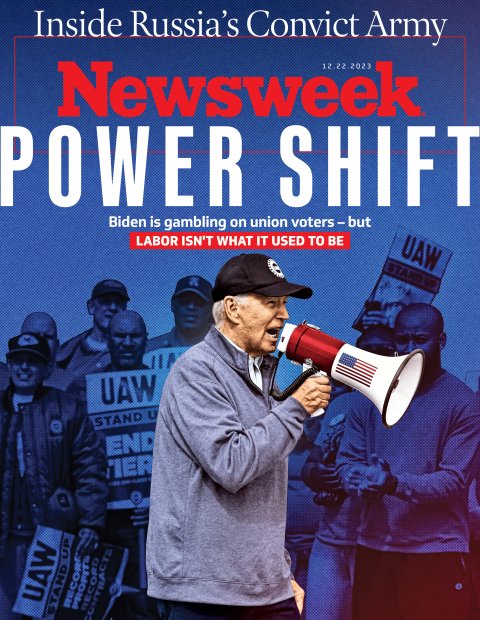

The American labor movement is having a moment. Wage earners across the country in a variety of jobs, from delivery drivers and health care providers to Hollywood scriptwriters and auto plant workers, have formed new unions, threatened labor stoppages or gone on strike this year, bringing entire sectors of the economy to a standstill. President Joe Biden made history this fall as the first sitting U.S. president to join striking workers on a picket line.

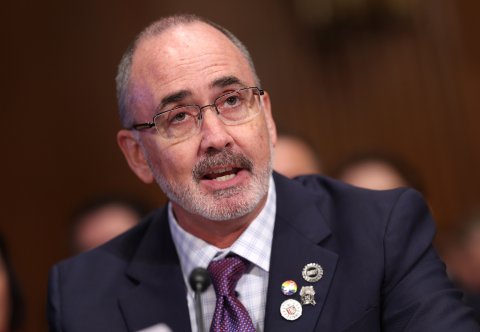

United Auto Workers President Shawn Fain summarized labor's new ethos in a recent speech, proclaiming what it claimed as a victory in contract negotiations with Stellantis, one of Detroit's big three automakers. "We didn't do it by begging the company, or agreeing to work terrible hours," Fain told supporters. "We didn't do it by giving back. We did it by fighting back."

Biden has given organized labor a lot to fight for. The three core pieces of domestic legislation that make up his "Bidenomics" agenda—the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, CHIPS Act and Inflation Reduction Act—will inject $2 trillion in new federal spending into the economy on infrastructure, clean energy and manufacturing over the next decade, according to a McKinsey & Company report. Much of the funding requires companies to work with unions, giving labor the biggest lifeline it's gotten in decades and a seat at the table to push for better work conditions in the rapidly evolving, 21st-century economy.

"We're at an inflection point because our economy is undergoing a big change," Joseph McCartin, a labor historian at Georgetown University, told Newsweek. "The labor revival now is all about workers wanting to have a say in what future work will look like."

Unions believe they have reason to feel optimistic. Democrats have embraced an increasingly progressive, union-friendly economic agenda over the past decade, and organized labor now has a staunch ally in the White House.

"Prior to Biden, Democrats viewed the labor movement as a constituency group to be managed, to be fostered, to have a transactional relationship with. Close allies, but not family members," Seth Harris, who served as Biden's top labor adviser before leaving the White House last year, told Newsweek. "Biden views organized labor as fundamental to his entire economic and social agenda."

The pandemic also shifted public attitudes about work. Coming out of COVID-19, younger Americans in particular expect better work conditions, and polls show a growing number of millennials and Gen Zers support organized labor. Overall, 68 percent of Americans say they approve of unions, according to Gallup, the highest level since 1965. Labor activity is also on the rise. There were 424 work stoppages nationwide in 2022, according to a tracker run by Cornell University, a 52 percent jump from previous year. This year has seen 383 labor actions through early December, among them the high-profile UAW strike.

But the auto industry standoff was also a reminder that unions still face entrenched opposition from corporations, the Supreme Court and other right-leaning courts. Republicans in Washington and state legislatures are also waging an aggressive campaign to weaken organized labor on the grounds that unions are bad for business. Just 10 percent of U.S. workers belong to a union today, a far cry from their post-World War II heyday.

"Government control of industrial and labor policy isn't the right approach," Mark Mix, the president of the National Right to Work Committee, a conservative lobbying organization, told Newsweek. The Biden administration is "putting its thumb on the scale" to boost unions but the effort is a gamble that might not pay off, Mix added. "Unions have relied on government power to expand their reach, and they haven't really expanded in numbers since the 1950s."

Inside the labor movement, there's widespread consensus that Biden's policies represent a rare opportunity to reverse decades of decline at a moment when millions of new jobs hang in the balance. To that end, AFL-CIO President Liz Shuler—the first woman to run the nation's preeminent labor organization—and other leaders are pursuing an overhaul to better position unions for the future. The effort is focused on pivoting to growing sectors of the economy and recruiting a new generation of young, diverse workers.

"That stereotype of the sort of industrial, hard-hat labor movement is an old stereotype," Shuler told Newsweek in an exclusive interview in which she shared new details of the AFL-CIO's plans to expand into the South and target clean energy and other emerging markets. "That's where the labor movement's challenge is. We're trying to actually expand and modernize, so we can be relevant and meet the needs of the future workforce."

The Union Push Behind 'Bidenomics'

The Biden administration push to modernize the economy is a massive undertaking. As a share of the nation's gross domestic product, Biden's plans represent the largest domestic spending program since the New Deal, according to an early analysis by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. It also represents the biggest effort in years to grow organized labor.

The infrastructure law was designed to ensure that federal funding for roads, highways, bridges and other projects would create as many union jobs as possible. White House officials who worked on the bill referred to this central design feature internally as the "Turducken strategy," Harris said. "We stuffed as much of the money into existing funding streams that already had prevailing wage requirements."

Unions were also prioritized in the Inflation Reduction Act, which requires companies to adopt prevailing wage standards and other labor-friendly practices in order to access billions in new clean energy tax incentives. In its first year alone the law created 170,000 new clean energy jobs and led the private sector to announce $110 billion in clean energy projects, according to the White House, which estimates the IRA will generate a total of 1.5 million new jobs in the renewable energy industry over the next decade.

The infusion of public and private sector investment is a game-changer for union workers, said Brent Booker, the president of the Laborers' International Union of North America, or LIUNA, a leading labor group in the renewable energy industry.

"It was hard for us to fully embrace these new technologies when our people were losing [fossil fuel industry] jobs at $25, $30 dollars an hour" and jobs in clean energy paid much less, Booker told Newsweek. "But now the federal government has a stake in the game," he said. "That turns the renewable world into union jobs."

Beyond clean energy, labor leaders view the moment as a prime opportunity to ensure unions are included in developing technological advancements in fields like quantum computing and AI. The CHIPS Act included $54 billion in federal funding to spur semiconductor manufacturing and help U.S. companies compete in the tech race with China.

As Biden-era policies come online, unions are also focused on expanding into southern states, despite the region's longtime opposition to organized labor, in response to the growing number of manufacturing companies moving to the South to produce electric vehicle batteries and other new technology.

Electric vehicle battery plants have already emerged as an early front in the labor movement's Southern strategy. There are now more than two dozen operating or planned EV plants in the United States, up from just two operational plants in the entire country in 2019, according to a TechCrunch report, and roughly half are in the South. The AFL-CIO expects 300,000 new jobs in EV plants to open up in coming years, with many slated for southern states."The South is essential to all the plans for growth," Shuler said.

Electric vehicles were a sticking point in negotiations between the United Auto Workers union and Ford, General Motors and Stellantis, during the recent six-week UAW strike punctuated by Biden's September 26 appearance on a picket line in Wayne County, Michigan. The tentative deal reached by the UAW and the automakers included provisions protecting union jobs in future EV battery plants.

The changing economy will force labor and business to make concessions to adapt to new technologies, Gerard Barron, the chairman and CEO of The Metals Company, told Newsweek. Barron's company, which plans to mine a section of Pacific Ocean seabed for minerals used in electric vehicle batteries, garnered headlines last year by signing a neutrality agreement with the UAW.

"You can find scenarios where everyone can win. But it does take a change in attitude of both parties," Barron said. "There's absolutely no purpose if you fight for member benefits and the industry becomes unsustainable. Where's the victory in that?"

The Changing Face of Organized Labor

If unions are poised to compete in the modern economy, it's due to decades of painful change. The organized labor movement that's rushing to embrace Bidenomics looks much different now than it has for most of its history.

The modern labor movement was born with the passage of the National Labor Relations Act of 1935. Better known as the Wagner Act, it established basic protections for private sector unions in a landmark victory for labor following years of clashes with industry. The groundwork laid by Franklin D. Roosevelt during the Great Depression bore fruit following World War II, when organized labor—dominated by traditional manufacturing and industrial unions—helped power the postwar boom.

That arrangement began to unravel in the 1970s. Faced with growing global competition, U.S. companies in search of cheaper labor moved domestic production from the Northeast and Midwest to the South and overseas. Anti-union conservatives began attacking labor, leading to Ronald Reagan's momentous decision to fire striking air traffic controllers in 1981. There were already signs that labor's power was waning. In 1979, the UAW made its first major concession ever in contract talks with one of Detroit's big automakers. But Reagan's firing of 11,000-plus union workers was a "symbolic turning point," Ruth Milkman, the chair of the City University of New York's Labor Studies Department, told Newsweek.

"It was a signal from Washington that it's open season on unions," Milkman said.

The North American Free Trade Agreement, signed into law by Bill Clinton in 1993, dealt a final blow to the old New Deal system of organized labor. Estimates vary, but NAFTA is believed by economists and labor experts to have cost the U.S. economy 600,000 to 1 million jobs in sectors of the economy where the work could be easily moved abroad. Manufacturing unions were among the hardest hit, accelerating the decline in factory work brought on by globalization and the Reagan era.

But while NAFTA hurt many traditional blue-collar unions, it created an opening for workers who can't be outsourced in sectors of the economy like retail, health care and service and hospitality. Led by the Service Employees International Union, or SEIU, unions expanded and gained new power after NAFTA.

"They were well-positioned to capture sectors of the market that were growing," Patricia Campos-Medina, a former top political official at SEIU, told Newsweek, "while the UAW, steel workers and building trades were still focused on how they would stop the government from letting manufacturing jobs bleed overseas."

The power shift has continued ever since, and it's reflected in the labor movement's changing demographics. The gender gap between men and women union members has dropped from 10 percent in 1983 to 1 percent in 2022, the latest data from the U.S Department of Labor shows. Today, nonwhite workers are driving gains in overall union membership: last year, the nation's unionized workforce grew by 200,000, and workers of color accounted for the entire increase, according to an Economic Policy Institute analysis of federal labor statistics.

An influx of younger Americans joining unions or showing interest in organized labor has also had a transformative effect, experts say. Recent internal AFL-CIO polling found that nine in 10 Americans under age 30 hold a favorable view of unions. Organized labor's promise of job protection is especially alluring to young people who came of age during the Great Recession and the pandemic, Milkman said. "There's a gap between the aspirations (held by) young people and the grim reality of the labor market," she said, and that's "fueling the new labor activism."

Labor's makeover is embodied by new leaders like Shuler, who won a historic election to lead the AFL-CIO in 2022. Shuler replaced Richard Trumka, an old-guard union leader who rose up through the ranks of the United Mine Workers of America and led the AFL-CIO for 12 years until his death in 2021.

Union Surge Faces Major Hurdles

But the union expansion push faces massive obstacles, starting with the fact that labor's target growth sectors—the same ones that stand to benefit most under Bidenomics—may prove to be the hardest to unionize.

Labor is already running into this problem in efforts to gain a foothold in the technology industry.

Tech giants like Amazon and Facebook's parent company Meta have well-established business models that don't rely on union labor, leaving little incentive for them to unionize. Unions are taking on Big Tech at a later stage in the industry's development, compared to past organizing drives in the early days of the auto industry and other key manufacturing sectors, said Harris, the former top Biden White House labor adviser and Obama administration labor official.

"Organizing is much, much, much more difficult now than it was before," Harris said. General Motors, for example, "was organized during the Depression. It already had unions in place, so when GM grew the unions grew," Harris said. "That was not the case with Amazon or Google or Facebook or any of these companies. You have to organize them after they've already become behemoths who really don't want unions."

Corporations across industries now spend more resources on union-busting, labor historians say. Companies are also adept at taking advantage of weak federal labor laws and ineffective oversight by the National Labor Relations Board, or NLRB, the independent federal agency that protects union rights. Last year, workers at an Amazon warehouse in Staten Island, New York, voted to unionize, joining a wave of successful organizing drives at Starbucks stores around the country. But Amazon and Starbucks delayed collective bargaining and the new unions still don't have contracts with better wage and job protections. The two companies aren't alone in using loopholes in the law to outmaneuver unions, experts say.

"In the United States, the laws protecting workers' rights to organize are weak. Employers can violate them at will without paying any major penalty," said Georgetown University's McCartin. "As long as they create a pretense of bargaining in good faith, they can bargain forever without reaching an agreement."

Democrats in Congress have proposed legislation, known as the Pro Act, to update the nation's main labor laws, most of which were written between the 1930s and 1950s. The effort is based on the recognition that the old laws dating back to Roosevelt's time need to be revisited to address modern labor challenges, said Saba Waheed, the director of the UCLA Labor Center.

"Today, the workforce looks different. The single Starbucks store unionizing looks very different from a Ford factory," Waheed said. "One hundred years ago, when another era of big industrial change was taking place, that's when the labor fight got more intense," she added. "It feels like that moment again."

But the efforts at labor law reform have run into ardent opposition from Republicans and influential business groups such as the United States Chamber of Commerce, who have argued that unions drive up business costs and help push jobs overseas to China and elsewhere.

A senior U.S. Chamber of Commerce official urged House lawmakers to oppose the latest version of the Pro Act, warning in a letter earlier this year that it would hurt employers and "allow for the disruption of entire segments of the economy." The Biden administration has taken steps to strengthen the NLRB. But critics say it hasn't done enough to counter efforts by Republican-controlled state legislatures to undo labor protections with "right-to-work" laws. Supporters of right-to-work laws—which are now in place in 28 states, including the entire southern U.S.—argue that they protect worker freedoms. Labor advocates believe they're intended to suppress unions.

The Supreme Court, meanwhile, has dealt labor several blows in recent years, including a 2018 ruling that nonunion members in the public sector don't have to help pay for collective bargaining activities. More recently, the court ruled earlier this year that in certain cases employers can sue striking workers for damages.

The battle for unions is especially hard in industries investing in the anti-union South. It's a commonly shared fear among labor leaders that the movement's recent momentum will stall as enthusiastic young organizers run into roadblocks in industries and regions of the country that haven't traditionally been friendly to labor. The concern is real, said Milkman, the CUNY Labor Studies chair.

"Suppose you're a millennial Starbucks barista and you were part of one of the stores that voted to unionize, but meanwhile nothing has happened. You've done all this work and you technically have a union but it doesn't have any clout in the workplace," Milkman said. "What we know from labor history is that when things do shift in a big way, it's not one workplace, one Starbucks or Apple store. It's a big surge. Maybe that's coming. You can imagine that scenario, but there's no guarantee."

Organized Labor's 'Secret Weapon' For 2024

The labor movement also needs Biden to win a tough reelection battle in order to maintain its momentum, in no small part to ensure his union-friendly policies aren't repealed by a Republican successor. The party's 2024 presidential candidates overwhelmingly oppose Biden's domestic agenda, starting with the Inflation Reduction Act.

Former President Donald Trump, the GOP frontrunner, has railed against the IRA since Biden signed it into law. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, former South Carolina governor Nikki Haley and other Republican White House contenders have promised to repeal the law if they become president. "The so-called 'Inflation Reduction Act' is a communist manifesto filled with tax hikes and green subsidies that benefit China," Haley, a former United Nations ambassador, wrote on X, formerly Twitter, on the law's one-year anniversary.

The first major bill that House Republicans approved under new House Speaker Mike Johnson would repeal billions in funding for Biden's climate programs. After the Inflation Reduction Act passed last year, Johnson called its climate and energy measures "green energy slush funds."

A second term would allow Biden to protect his legacy, while overseeing the implementation of provisions in the IRA and other laws intended to maximize the number of new union jobs. Four more years under Biden would also give the National Labor Relations Board more time to ramp up enforcement of labor violations, labor experts said.

The AFL-CIO will be more involved in 2024 than it has been in previous election cycles, Shuler told Newsweek. In a break from the past, "our political program is now [operating] 365, every day of the year," she said, with a focus on "places where the Democratic Party is sort of in-build mode." Shuler added: "We can reach real working people in actual workplaces at a drop of the hat, in any given moment. That's kind of our secret weapon. We do that in Arizona. We do that in Nevada."

The labor movement and the Democratic Party share a similar battleground map, underscoring the overlap between the two. Arizona, Georgia and other states where unions hope to organize future jobs helped Biden win the White House in 2020, and they'll be critical again next year in an election where the economy will be a top issue. The strategy isn't lost on Republicans and union opponents.

Mix, of the National Right to Work Committee, said Trump's visit to a nonunion plant in Michigan on the same day that Biden joined the UAW picket line underscored the likely GOP nominee's enduring appeal to many union voters. "I don't think he's lost appeal with rank-and-file union members," Mix said of Trump. "His message is holding."

Still, Biden beat Trump by 16 points among voters from union households in 2020, according to national exit polls. To pull that off again, he'll have to mobilize traditional, rank-and-file union workers as well as the younger, more progressive activists who represent the future of organized labor, Kait Sweeney, a progressive consultant, told Newsweek.

"The future of the Democratic Party is intertwined with the labor movement," Sweeney said. "There's no greater proof of that than seeing Joe Biden walking the picket line."