An international team of researchers claims to have dated mysterious cave art in Borneo—a southeast Asian island that is the third largest in the world—to as early as 40,000 years ago, placing the works among the oldest known figurative depictions in the world. That's according to a study published in the journal Nature.

Figurative artworks are those which are not abstract designs and depict real things, such as animals, humans and other objects.

The team says that the findings lend support to the view that cave art—one of the most important innovations in human cultural history—was being practiced in Southeast Asia at the same time as Europe, contrary to scientists' long-held views.

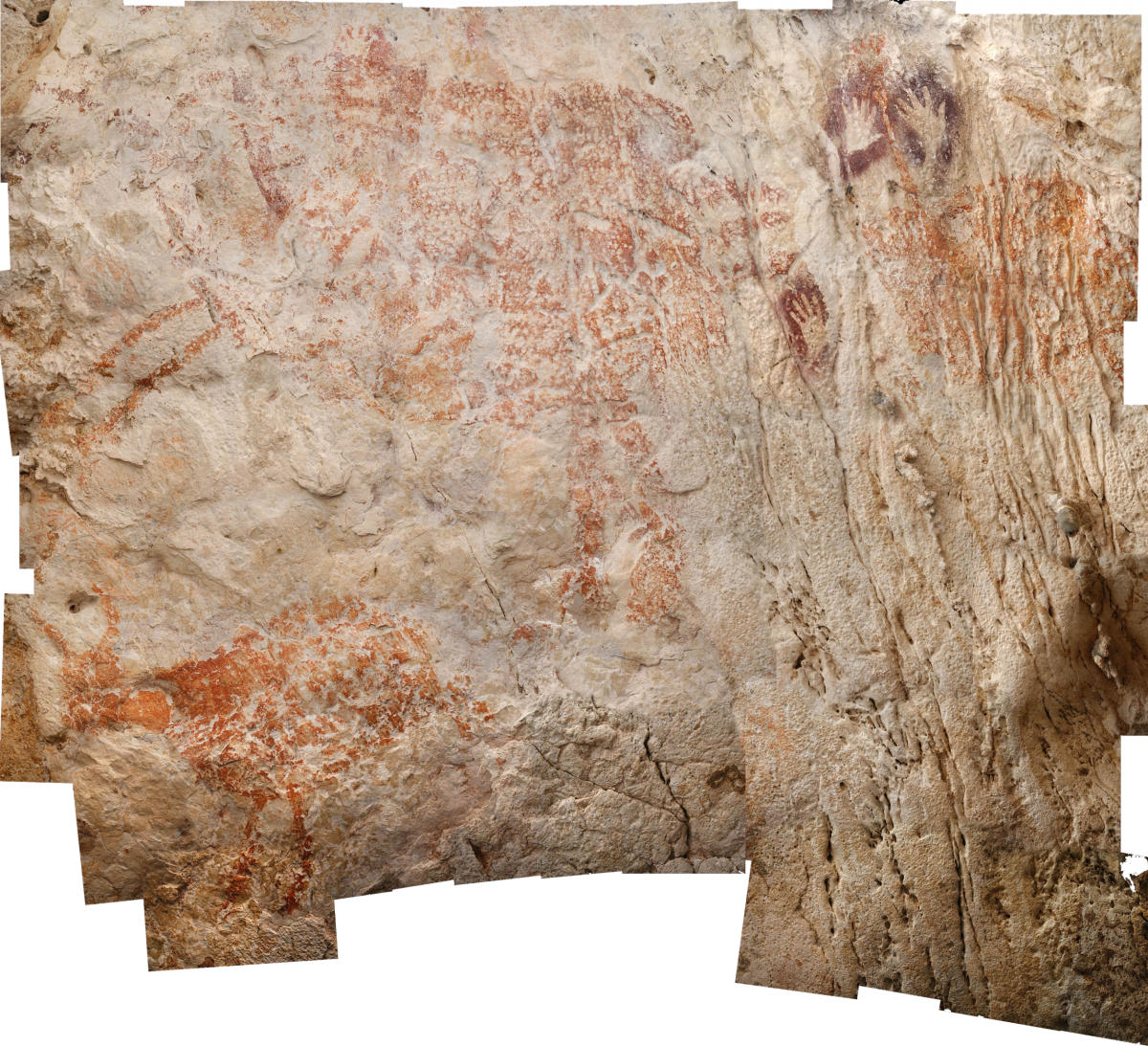

For more than two decades, researchers have known about caves in the remote and rugged mountains of East Kalimantan—an Indonesian province of Borneo—which contain prehistoric paintings, drawings, and other imagery, including thousands of depictions of human hands (stencils), animals, abstract signs and symbols and other motifs.

According to the team led by Maxime Aubert from Griffith University, the results of Uranium-series dating show these artworks are older than previously thought. This technique does not date the pigments used in the paintings themselves but instead examines a layer of calcium carbonate, also referred to as calcite, which forms over it, or was present before the work was made.

"Uranium is radioactive and with time it decays to make another element, thorium," Aubert told Newsweek. "The rate of decay is precisely known. The key is that uranium is soluble in water, but thorium is not. So, when a calcite coating forms from rainwater on top of a painting, it initially contains uranium but no thorium. If we take a sample thousands of years later and measure the ratio of uranium versus thorium, we can calculate the age of the coating."

"The calcite layer on top of the painting provides a minimum age for the art and the layer underneath provides a maximum age," she said. "For uranium-series dating, we have to demonstrate that the coating is relatively pure, and that the calcite is a close system for uranium and thorium. We were able to meet these conditions."

The oldest piece of art the team dated—a large painting of an unidentified animal, probably a species of wild cattle—was found to have a minimum age of 40,000 years old, making it the oldest known figurative artwork, according to Aubert.

In addition, stencil art in the caves was shown to be of a similar age. One of these works, for example, was shown to have a maximum age of around 52,000 years.

The research also uncovered a major change in style within this culture around 20,000 years ago, marking a transition from depicting the animal world to the human world at a time when the global ice age climate was at its most extreme.

"Who the ice age artists of Borneo were and what happened to them is a mystery," Pindi Setiawan, an Indonesian archaeologist from the Bandung Institute of Technology and co-author of the study, said in a statement.

The research suggests that the picture of how cave art emerged is complex, casting new light on the long-held view that Europe was the center for its development. Even though Borneo is now an island, throughout most of the ice age it lay at the easternmost tip of the vast continental region of Eurasia—with Europe at the westernmost tip.

"I think we're starting to see a pattern where cave art seems to have developed and evolved more or less at the same time and in a similar way at opposite sides of the world [Borneo and Europe]," Aubert said.

In 2014, Aubert and colleagues published a study which revealed that similar cave art appeared on the island of Sulawesi—to the east of Borneo—at least 39,900 years ago. This island was likely a vital stepping-stone between Asia and Australia.

"Our research suggests that rock art spread from Borneo into Sulawesi and other new worlds beyond Eurasia, perhaps arriving with the first people to colonize Australia," she said.

Wil Roebroeks, a professor of paleolithic archaeology from Leiden University in the Netherlands, who was not involved in the latest research, described the most recent paper as a "very solid study."

"These dating results are extremely interesting, solid and complement a previous pioneering study by Maxime Aubert and colleagues on Sulawesi," he told Newsweek. "The various phases of rock art production/styles they now identify on the basis of their dates seem to make sense."

"Their 2014 paper on Sulawesi made a very big splash, as it showed that cave art was practiced both in Europe and in southeast Asia at about the same time, before 40,000 years ago," he said. "The current paper adds very solid, important data to the new (2014) picture."

However, not everyone is convinced that the latest results provide concrete evidence for the oldest known figurative painting.

"I have no doubt that they have dated painting to at least 40,000 years ago at their oldest site, and this is an exciting result as it shows that cave painting [in the region] wasn't an isolated event, but that it had a wide geographical distribution," said Alistair Pike, a professor of archaeological science from the University of Southampton.

"But there are some doubts if their dated sample overlies the figurative art," he told Newsweek. "It appears to lie over some pigment 15 centimeters away from the animal figure. While it once might have formed part of this figure (which is very weathered), they have not demonstrated it is part of it. Since the pigment most likely derives from painting, it shows that the tradition of painting caves appeared in Borneo at about the same time as it did in Sulawesi, but it may not be figurative painting."

Pike was part of a research team which announced earlier this year that they had dated cave paintings at three sites in Spain to a minimum age of 64,000 years old, making them the world's oldest known examples. The implication is that these works were created by Neanderthals—because modern humans were not present in the region at the time—although this art is not figurative, consisting of only dots, lines and hand stencils.

The lead researcher on the Neanderthal art team, Dirk Hoffmann, from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, also criticized some of the methods used to date the animal painting to a minimum age of 40,000 years old in the latest study.

"Initially I was quite enthusiastic when I learned that there are new, apparently exciting results on cave paintings from this important region," he told Newsweek. "But honestly, I am disappointed on quite a few aspects."

"It is not certain that Aubert et al. dated an animal painting to be older than 40,000 years old," he said. "The pigment could also be part of a hand stencil and thus they might have dated the stencil. They basically speculate that the pigment they dated was part of the figure."

Furthermore, Hoffmann also noted that Aubert and her colleagues didn't discuss the results of the Neanderthal art study in their paper, and also ignored existing evidence for engravings on egg shells and ocher pieces in South Africa dated to 60,000 and 73,000 years ago respectively, which rank among the earliest art ever created.

"This is scientifically disappointing," he said. "I have the feeling that, by all means, they try to keep a narrative that rock art emerges around the same time in Borneo and Europe and was exclusively made by modern humans. The Neanderthal paintings with ages older than 64,000 years old are all non-figurative, but nevertheless still completely ignored by Aubert et al."

Roebroeks—who was not involved in the Neanderthal art study either—echoed these sentiments, saying the latest conclusion that cave art arose at the same time in southeast Asia as it did in Europe should be viewed with caution.

"In the context of a discussion of the origins of rock art the [latest] paper could at least have been mentioned, even though the current Borneo study one is more focused on figurative rock art," he said. "Hoffmann et al.'s results, if corroborated, indeed question whether it is "now evident that rock art emerges in Borneo at around the same time as the earliest forms of artistic expression appear in Europe in association with the arrival of modern humans (45,000–43,000 years before the present).""

This article has been updated to include additional comments from Alistair Pike, Dirk Hoffmann and Wil Roebroeks.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Aristos is a Newsweek science reporter with the London, U.K., bureau. He reports on science and health topics, including; animal, ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.