Archaeologists believe sets of fake amber beads discovered at Spanish burial sites are the first known examples of faked jewelry in European prehistory.

For the study published in the journal PLOS One, archaeologists looked at two sets of centuries-old beads. Two dating back to the third millennium B.C. were found at the artificial cave of La Molina in the city of Lora de Estepa, southern Spain. At the site, 10 people were buried alongside goods including pottery vessels, bone awls and objects carved out of ivory.

Another four from the second millennium B.C. were found at the Cova del Gegant cave in the coastal town of Sitges, to the southwest of Barcelona. There, almost 2,000 human bones from the Middle Bronze Age thought to belong to 19 people were discovered, as well as pieces of pottery, and ornamental beads made of lignite, coral, amber, shell and gold.

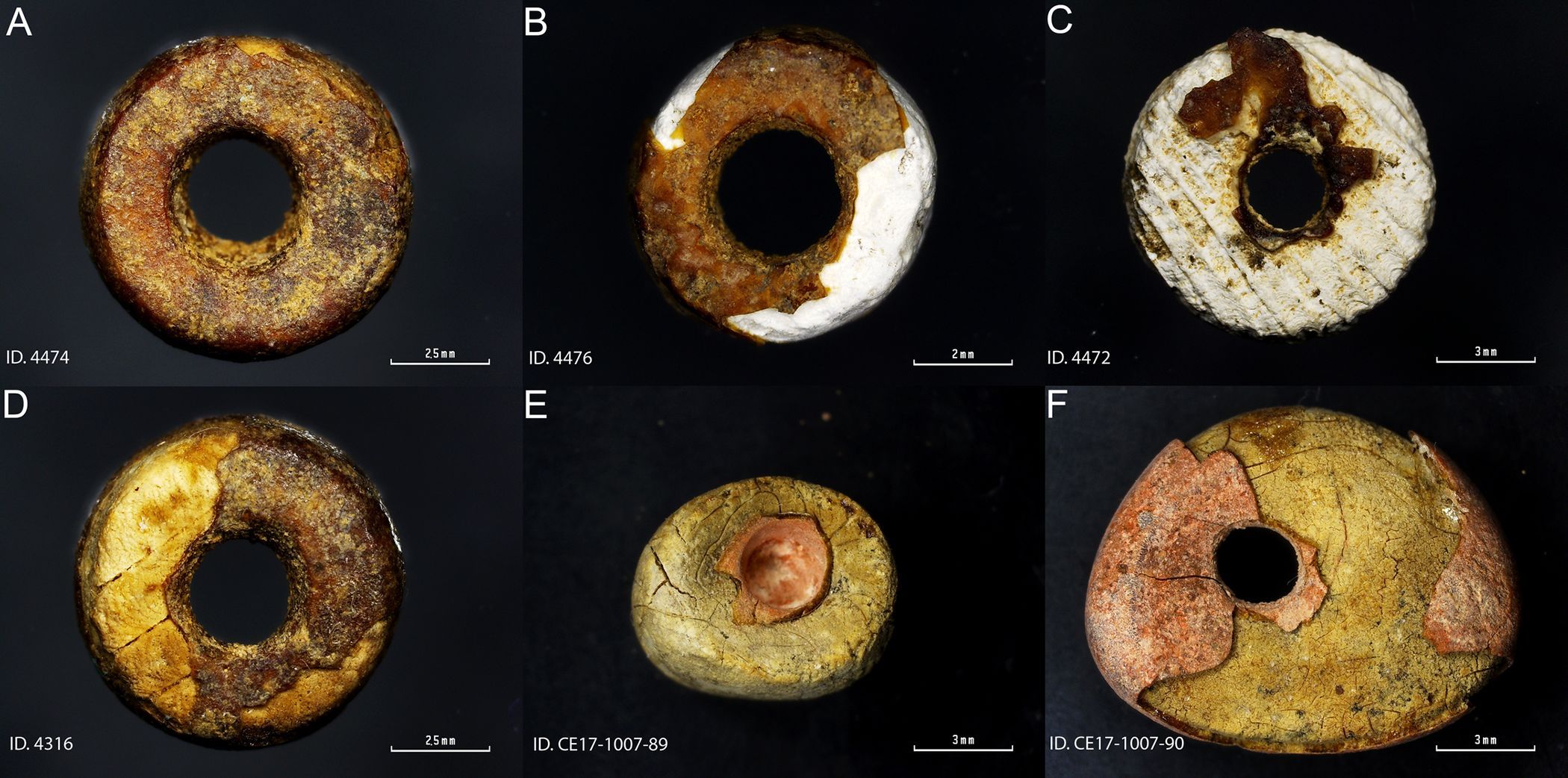

The specimens looked like amber, and many archaeologists were tricked by the beads, study co-author Carlos P. Odriozola, professor at the University of Sevilla Department of Prehistory and Archaeology, explained to Newsweek. But tests revealed the Cova del Gegant beads were in fact a mollusk shell core coated with what is believed to be pine resin, and were found near real amber beads. Meanwhile the La Molina beads were in fact seeds coated in resin.

"With this type of surface coating it was possible to emulate effectively the translucence, shine and color that made amber such an appreciated material," the authors wrote. Similar methods of imitating turquoise in the Levant from the sixth millennium B.C. have been identified in past research.

"These two archaeological sites resemble each other in many ways despite the geographic and chronological differences and point to technical practices and knowledge in Late Prehistory that would have been more frequent than tends to be documented, as other finds in the Near East have shown," they authors said.

Odriozola explained that people started to trade commodities and valuables as farming emerged as a way of life in Europe thousands of years ago. Amber, which is made of fossilized tree resin, was a highly valuable material exchanged across the continent and used by leaders to cultivate an image of power and flaunt their wealth. Succinite amber was brought into Spain from the Baltic sea and simetite amber from Sicily. This route also brought in Asiatic and African ivory, Alpine jade, and cinnabar.

"The fact that a wealthy individual from La Molina cave was buried with an amber-like artifact opens a pathway to research on the trading network and the role of middleman (traders) and valuable supply systems in these communities from the third millennium B.C.," Odriozola said.

"Something similar happens in Cova del Gegant where individuals from the second millennium B.C. were buried with two genuine amber beads and four amber-like beads."

So why were the counterfeit beads created? Experts aren't sure. The authors remarked that it is curious that "exotic materials" were found in both tomb sites, suggesting the dead were wealthy enough to afford rare goods and genuine amber.

Odriozola suggested it could be that there wasn't enough amber to meet demand, or perhaps traders simply wanted to cheat the wealthy out of money.

The study should encourage experts to reconsider whether valuable prehistoric items really are what they appear to be, said Odriozola.

Peter van Dommelen, professor of archaeology and anthropology at Brown University who was not involved in the research, told Newsweek: "This study is new and interesting but not necessarily significant in its own right. The really significant part was done five to 10 years ago when it was shown that amber in this early prehistoric period did not come from the Baltic but from Sicily.

"This find adds an interesting touch to it, and opens the door to a better understanding of how and why such items were traded and 'faked'—the association with North African ivory is crucial in this regard, and the North African involvement is perhaps the major insight that is coming out."

He argued more than scientific analysis looking at the provenience of materials needs to be done, and the study needs to be followed up by more sophisticated interpretive frameworks.

Archaeologists believe humans have been adorning themselves with jewelry for hundreds of thousands of years as a means of communication: whether using a ring to indicate marriage or to reflect their social status, according to Michelle Langley, ARC DECRA research fellow at Griffith University.

The earliest known examples of bodily adornments are the mineral red pigments used in Africa as paint some 285,000 years ago.

"For archaeologists, finding body adornments is the closest thing to finding prehistoric thought. Their first appearance in the archaeological record tells us when the human mind had become sophisticated enough to conceive of individual identities," Langley wrote for The Conversation.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Kashmira Gander is Deputy Science Editor at Newsweek. Her interests include health, gender, LGBTQIA+ issues, human rights, subcultures, music, and lifestyle. Her ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.