The '60s are turning 50. Not the 1960s, but the era we call the '60s, whose highest highs and lowest lows were nearly all in the second half of that decade and the first half of the one that followed: the founding of the Black Panthers (1966), the Summer of Love (1967), Nixon (1968), Woodstock (1969), Watergate (1973).

We were a teenage nation then, lolling on the lawns of Golden Gate Park, puffing on grass, protesting Vietnam. Now we have grown thick around the middle and gray around the temples, our indignation reserved mostly for our property taxes. The days of acid, and of rage, seem so very long ago. Eldridge Cleaver, the ferocious Black Panther who advocated the rape of white women as a revolutionary act, died a Republican. The Yippie leader Jerry Rubin went to Wall Street. Bob Dylan made an ad for Victoria's Secret. It's all right, ma. I'm only investing in renewable fuels.

But just as they seemed ready for a valedictory round of "Send in the Clowns," the '60s have returned with surprising vigor, eager to make one last point before shuffling off the stage, the uncle whose rambling stories have started to make sense.

When, Colin Kaepernick, a backup quarterback for the San Francisco 49ers, began refusing in mid-August to stand for "The Star-Spangled Banner," citing racial prejudice in the United States, The Ringer, a website that covers the culture of sports, declared, "1968 Has Been Rebooted."

Last winter in Chicago, crowds turned out to protest the unjustified shooting of Laquan McDonald, a black teen, by the police. Bobby Rush, a congressman who had once been a Black Panther, concluded as he observed the scene that it was "1969 all over again."

Complained the conservative American Conservative: "Everywhere today, it would seem, there is the stench of the 1960s."

"1971 All Over Again," said Slate about the current presidential campaign.

Washington Monthly: "Is It Almost 1972, Again?"

For a nation built on relentless progress, it's remarkable that we look back so often—and that so much of the retrospection is focused on a narrow band of time whose facts are not in wide dispute. Sometimes, the retrospection seems closer to re-enactment, with kids smoking in Haight-Ashbury again. The revolution is back, this time with its own emoji.

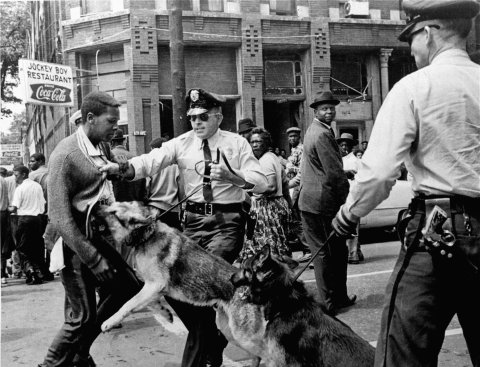

The '60s were about awakening; one of the great compliments an individual can confer on social media today is that someone is "woke." The term comes from black users of Twitter, implying an understanding of the nation's racial conundrums. This also is an analog to the '60s, whose moral force came from the civil rights movement, culture and politics coming together as a black man, Jimi Hendrix, played a furious version of "The Star-Spangled Banner" at Woodstock. Back then, as Bryan Burrough wrote in last year's indispensable Days of Rage: America's Radical Underground, the FBI, and the Forgotten Age of Revolutionary Violence, many were awakened by television images of Southern racism; today, one is made woke by Twitter evidence of police brutality. They had black-and-white footage of Bull Connor's dogs let loose in Birmingham, Alabama; we have cellphone video of Eric Garner struggling to breathe, the Facebook Live stream showing Philando Castile shot dead in his car.

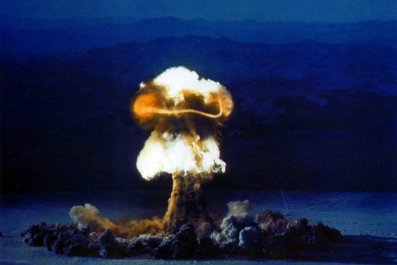

There is also the conviction, then as now, that American life has fogged over with opalescent falsities, that we need the purifying burn of truth. In the '60s, truth might have come from Timothy Leary and Abbie Hoffman or, if you leaned right, the stern soliloquies of Richard Nixon. Fifty years later, truth-telling is in vogue again, as any supporter of Bernie Sanders or Donald Trump will all too happily inform you. Accordingly, another popular social media injunction is to "keep it 100," a call for intellectual honesty that evokes the words of John Lennon: "Just gimme some truth."

In London, the Victoria and Albert Museum is holding an exhibit called "You Say You Want a Revolution? Records and Rebels 1966-1970." One of the curators said on a press tour of the Bay Area this summer , "In the context of the extraordinary times that Europe and U.S. are living through, 2016 is a fitting year to look at this period from today's perspective. This could be a message of hope for our times."

A message of hope, sure. And a warning.

The Summer of Love-Hate

It's a common belief that the '60s began nearly four years after the 1960s did, with the assassination of John F. Kennedy. Nearly everything we think of as associated with that era—Vietnam, the Summer of Love, Woodstock, Manson, Altamont, the Black Panthers—followed that infernal motorcade through Dealey Plaza.

When the '60s ended is harder to say. It is also the more important question, since so many aspirations seemed to have died with the '60s. Homer Simpson claims the '60s ended in 1978, but this is not a commonly held opinion. Joan Didion wrote about the '60s ending in 1971, when she moved to "a house on the sea" to escape the bad vibes of the Manson family murders, wafting through the canyons of Los Angeles. Watergate, which broke in 1972 and caused Nixon's downfall, is frequently cited as the end of an era whose beginnings are rooted in Kennedy's narrow victory over Nixon in 1960. The conservative commentator Hugh Hewitt wrote in The Weekly Standard that the '60s ended on 9/11.

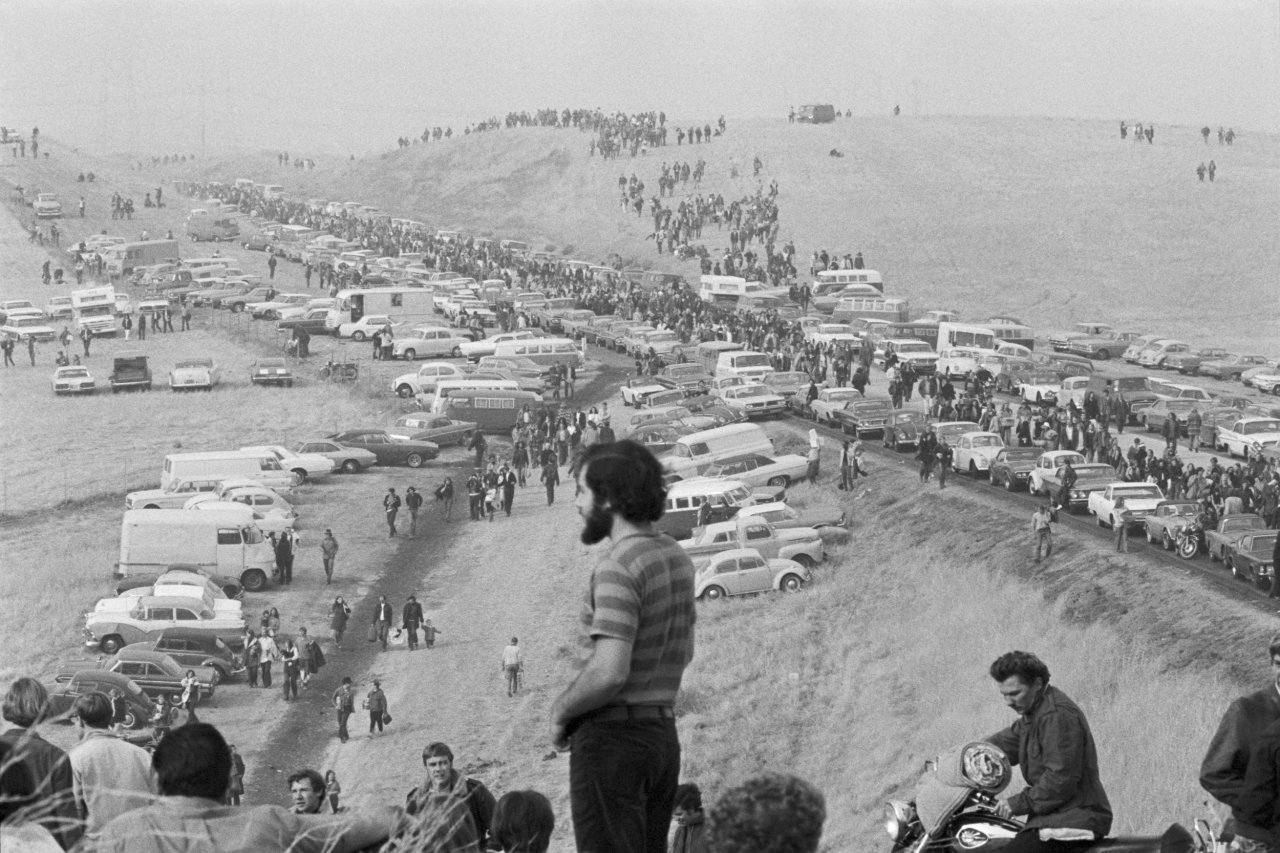

A more popular view is that the '60s ended on December 6, 1969, at the Altamont Raceway Park in Northern California. You get there by heading due east out of San Francisco, over the Berkeley Hills, into the beginnings of farm country, where the trees are few and the grass is an unnatural shade of yellow. The Altamont Free Concert was supposed to be a West Coast counterpart to Woodstock. And it was, in all the worst ways. The famous farm in Bethel, New York, remains a site of pilgrimage for those who want to remember the best of the '60s, the grooviest moments of a time that, under the forensic light of history, seems to have been rather frequently ungroovy. The Altamont Free Concert inspires no fond memories and, consequently, no visitors.

The racetrack shuttered eight years ago, without much notice. As I walked toward the site where the concert took place, ground squirrels and lizards skittered through the weeds growing between the many cracks of Altamont's hot pavement. A single charred car sits in the middle of the bowl, an apt metaphor for a generation that convinced itself that it was better to burn out than to fade away.

Already, the raceway has the feel of ancient ruin: the tilted light poles like the columns of a toppled temple, the advertisements coated with dust, the ghostly stands occupied only by the stray crow. You could easily believe that the last time anyone convened here was that fall evening in '69, as Mick Jagger pranced with rising unease through his set, and Grace Slick, the lead singer of Jefferson Airplane, looked out at the chaotic scene before her and pleaded, "Let's not keep fucking up."

The Rolling Stones had wanted to play San Francisco, but the permitting process went awry, so the best they could do was a racetrack whose owner coveted the publicity so badly he offered up the venue for free. Promised the lighting designer Chip Monck, "This is going to be like a little Woodstock, you know?"

Altamont was nothing like Woodstock. Four people died there: a drowning, a car crash and, most notoriously, the killing of a black man, Meredith Hunter, by the Hell's Angels motorcycle gang, who were paid $500 worth of beer to work security. There were three deaths at Woodstock (a heroin overdose, a burst appendix and a tractor accident), but those feel aberrant, while the footage of a Hell's Angel plunging his knife into Hunter's neck seems like the bloody inevitability toward which Altamont had been hurtling.

Altamont was doomed from the start. This was farm country in 1969, and though the Bay Area's swollen tech sector is today seeping eastward, it is mostly farm country still, with irrigation canals weaving blue ribbons through the land. It was on the California Aqueduct that death first visited Altamont: After giving a police officer the middle finger, a teenager from Buffalo, New York, named Leonard Kryszak jumped into the water. The flow was quick, and the water was cold. Kryszak stood no chance.

The one death everyone knows of is that of Hunter, during the Stones' set. The killing happened near the stage, which was so low the performers were essentially in the crowd. The Stones could plainly see that something bad had happened, and yet they kept playing. It wasn't their show anymore. They were just providing the soundtrack to the Hells Angels, whose violence was the most memorable performance of Altamont.

Although the death of Hunter is the gruesome pinnacle of Altamont, there is another moment that is even more revealing. As the Stones stepped off the helicopter that had taken them from San Francisco to Altamont, a fan rushed up to Jagger and punched him in the face. Jagger went down, then sprung back up, street-fighting man that he was, and the band continued walking to its trailer.

As horrific as it was, the Hunter killing could be explained through the Hell's Angels racism and thuggishness, fueled by strong acid and cheap wine. But there was nothing to explain the assault on Jagger, other than the assertion of H. Rap Brown, the Black Panther leader, that violence is "as American as cherry pie." Jagger acknowledged the madness of the scene when, after the concert, a Chronicle reporter reached him at the Huntington Hotel in San Francisco.

"If Jesus had been there, he would have been crucified," Jagger said. "What happened?" he wondered. "What's gone wrong?"

The '60s have plenty of detractors, and those detractors have all the evidence they need in Altamont, a tombstone flower children carved for themselves. Yet "Altamont was not the end of anything," argues Joel Selvin in his fine new book, Altamont: The Rolling Stones, the Hells Angels, and the Inside Story of Rock's Darkest Day, which rivetingly re-creates the disaster in its awesome fullness. Selvin, a longtime critic for the San Francisco Chronicle, makes no excuses about Altamont, making clear that it was Woodstock's evil twin in every way imaginable. But he also refuses to feed the simplistic narrative of cultural demise. "It certainly wasn't the end of the '60s," he says, "in some definitive, apocalyptic way, as it is often portrayed."

'Death to the Fascist Insect'

When I met Selvin for a beer, I asked him when he thought the '60s ended, if not at Altamont. "Oh," he said quickly, "with the fall of Saigon"—in 1975.

We were sitting at Brennan's, a dim sports bar inside what used to be Berkeley's train station. There are far superior bars in Berkeley, with wine lists as long as congressional farm bills, but Selvin retains an affection for this place. He mentioned, as we spoke about Altamont, that he'd lunched there a couple of times with one of the most famous figures from the '60s: Patricia Hearst.

Hearst is the subject of another book about the death of the '60s published this past summer: Jeffrey Toobin's deliciously disconcerting American Heiress, about the 1974 kidnapping of Hearst, granddaughter of newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, by a hapless outfit that grandly called itself the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA). Altamont showed the danger of excessive tolerance; the Hearst saga showed the danger of excessive conviction. Theodor Adorno said it was barbaric to write poetry after Auschwitz. Similarly, it was ridiculous, after Hearst, to write political manifestos in Berkeley and Morningside Heights.

Toobin has an eye for hypocrisy, which served him so well in his book on O.J. Simpson, The Run of His Life, and an acute nose for the bizarre. The SLA forced the Hearsts, who were much less wealthy than popular belief held, into funding a massive food distribution program (People in Need) that is surely one of the more transactional philanthropic efforts in American history, second only to the charitable giving of the Trump Foundation. The effort was aided by the Nation of Islam, while Ronald Reagan, then the governor of California, showed the extent of his compassion by joking, "It's just too bad we can't have an epidemic of botulism."

From captivity, Hearst released dispatches that suggested an increasing identification with the SLA, which the Black Panthers and most other revolutionary organizations had denounced. She would have made a fine Twitter personality, fulminating against the Koch Brothers and Israel. Instead, she took up arms.

As Hearst morphed from prisoner to comrade, she proudly adopted the nom de guerre "Tania." She wielded machine guns and robbed banks, vowing, in her dispatches from the underground, "death to the fascist insect that preys on the life of the people." This, from a scion of Citizen Kane. Marx predicted that history would curdle from tragedy into farce, but he said nothing about the Summer of Love turning into a season of mayhem. And weren't we a nation that was beyond history, anyway?

American Heiress is the story of Patricia Hearst, but also the story of a left seduced into bloodshed. In Days of Rage—the most authoritative account there is of violent 1970s avant-gardism in the U.S.—Burrough wrote, "During an eighteen-month period in 1971 and 1972, the FBI reported more than 2,500 bombings on U.S. soil, nearly 5 a day." Most of these were not fatal, yet the nation could only countenance these campaigns for so long. Children are permitted tantrums, but the tantrums have to end. The radicals had all the conviction of the Bolsheviks who stormed the Winter Palace; what they lacked was good marketing. Editorialized The New York Times: "Every building bombed, every person killed or wounded by bombs horrifies and makes more angry the great majority of the American people who abhor all political violence."

Brown was right about violence as cherry pie, but man cannot subsist on pie alone. The left back then bombed itself into irrelevance; the right is doing it today, with the average Donald Trump rally some combination of World Wrestling Entertainment match and Ku Klux Klan rally, set to latter-day Kid Rock jams. Americans are not the French: They recoil from extremism even faster than they recoil from soccer. The '60s got what they deserved: Ronald Reagan and John Cougar Mellencamp. Today's firebrands bring their firearms to college campuses, assassinate abortion doctors, assault protesters exercising their First Amendment rights. They too will get what they deserve, most likely in the form of Hillary Clinton.

You Say You Want a Tractor-Mower

Hearst certainly did OK for herself—better than average homegrown terrorists, like most of her SLA comrades, who ended up riddled with bullets and charred in an inferno. She spent not even two years in prison, winning clemency from Jimmy Carter. Later, Bill Clinton granted her a pardon. "Rarely have the benefits of wealth, power, and renown been as clear as they were in the aftermath of Patricia's conviction," Toobin writes.

Last year, as Toobin was completing his book, the gossip page of the New York Post reported that Hearst was furious. A source told the Post that Hearst called Toobin a "hack writer" and "an emotional rapist." That's not fair, since so much of Toobin's work is Hearst's own words and well-chronicled deeds. Like the Beatles' Sexy Sadie, she broke the rules and laid it down for all to see.

Hearst was recently in the news for an altogether unrelated accomplishment: In 2015, her shih tzu, Rocket, won the toy dog category at the Westminster Kennel Club dog show. Having spent her young adulthood in the crucible of leftism that was the Bay Area, she moved to a place least likely to foment revolution, a corner of the republic where for decades—nay, centuries—the gilded classes have been soothed by the gentle breezes off the Long Island Sound: Connecticut.